Great Curassow Crax rubra Scientific name definitions

Text last updated January 2, 2019

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Catalan | hoco de carúncula groga |

| Czech | hoko proměnlivý |

| Dutch | Bruine Hokko |

| English | Great Curassow |

| English (United States) | Great Curassow |

| French | Grand Hocco |

| French (France) | Grand Hocco |

| German | Kronenhokko |

| Icelandic | Bóluhúkur |

| Japanese | オオホウカンチョウ |

| Norwegian | storhokko |

| Polish | czubacz zmienny |

| Russian | Большой кракс |

| Serbian | Veliki hoko |

| Slovak | hoko hrbozobý |

| Slovenian | Velika hokojka |

| Spanish | Pavón Norteño |

| Spanish (Costa Rica) | Pavón Grande |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Pavón (Paujil) Grande |

| Spanish (Honduras) | Pajuil |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Hocofaisán |

| Spanish (Panama) | Pavón Grande |

| Spanish (Spain) | Pavón norteño |

| Swedish | större hocko |

| Turkish | Kıvırcık Hokko |

| Ukrainian | Кракс великий |

Crax rubra Linnaeus, 1758

Definitions

- CRAX

- rubra

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

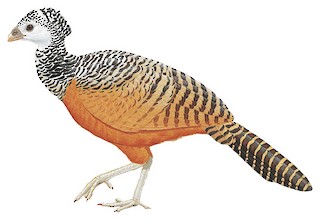

The Great Curassow is a physically large Cracid that ranges from Mexico south to Ecuador. It is a secretive species found in humid tropical forests that feeds mostly on fruits but also eats small invertebrates as well as vertebrates. Males are black with white under parts, a shaggy crest and a bright yellow spherical knob on the bill. Females are polymorphic, usually either barred (rare), rufous, or blackish. The Great Curassow have varying calls that range from low frequency booms to high-pitched yips. The species is declining due to habitat loss and overhunting, but it still can be seen stealing across the forest floor or feeding in the upper levels of the tree canopy.

Field Identification

Male 87–92 cm, 3600–4800 g; female 78–84 cm, 3100–4270 g. Crest very well developed ; this and prominent knob on bill separate male of present species from <em>C. alector</em> , the only other Crax with uniform black tail and yellow cere. In contrast to some congeners, e.g. C. daubentoni, knob size is not positively correlated with age in present species (1). Unlike any other curassow, female has three morphs; barred morph rare; intermediates between dark and red morphs may occur, as may those of barred and dark morphs; dark and barred morphs unknown in South American part of range, while red morph does not occur in Mexico. Immature male initially similar to dark-morph female , but darker; black adult plumage acquired long before bird fully grown; immature lacks knob on bill. Immature females of all morphs similar to adults. Race griscomi smaller, with some slight colour differences in females.

Systematics History

Editor's Note: This article requires further editing work to merge existing content into the appropriate Subspecies sections. Please bear with us while this update takes place.

C. globicera is a synonym of present species. Most closely related to C. daubentoni and C. alberti (2). Has hybridized in captivity with C. alberti and C. alector, producing fertile offspring. Bogus forms “C. chapmani” and “C. hecki” described from females of rare barred morph. Birds occurring S from S Nicaragua described as a separate species, “C. panamensis”, but not now accepted even as a race. Taxonomic revision of populations required, especially in S of range, as undescribed races may be found. Two subspecies recognized.Subspecies

Crax rubra rubra Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Crax rubra rubra Linnaeus, 1758

Definitions

- CRAX

- rubra

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Crax rubra griscomi Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Crax rubra griscomi Nelson, 1926

Definitions

- CRAX

- rubra

- griscomi

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Distribution

Editor's Note: Additional distribution information for this taxon can be found in the 'Subspecies' article above. In the future we will develop a range-wide distribution article.

Habitat

Heavy rainforest in tropical and lower subtropical zones; usually occurs in lowlands, but also in foothills up to altitudes of c. 1200 m, sometimes higher, e.g. in Volcán Barú, Panama, where species has been recorded up to 1900 m, but only up to 700 m in Ecuador (3). In Yucatán, Cozumel I and parts of Costa Rica also occurs in seasonally drier forest , although, unlike Penelope purpurascens, is absent from drier forests of W Mexico. On Cozumel I, occurrence closely tied to the presence of two trees, Manilkara zapota and Mastichodendron foetidissimum (Sapotaceae) (4). Occasionally ventures into ravines, and, if unmolested, into partially cleared areas or even plantations.

Movement

Sedentary, although local people report that the species is present in Yaxchilán Natural Monument, Chiapas, Mexico, only during the dry season (5).

Diet and Foraging

Fruits, including figs and those of Spondias (Anacardiaceae), Chione (Rubiaceae) and Casimira (Malpighiaceae); usually fruits fallen from trees taken from ground, but sometimes also those still on trees, mainly in low branches, or shrubs; fruits can be eaten when hard and green. Study in El Salvador reported fruits of 15 plant species in diet, along with leaves (four species), and some invertebrates (3–4 species) (3), while a Guatemalan study identified plants belonging to 44 species and 17 families in this curassow’s diet, of which Lauraceae, Moraceae and Sapotaceae constituted 62% of vegetable matter, and 79·5% of diet by dry weight was fruit or seeds; just 2·5% of diet comprised arthropods (22 species from six orders), mostly a species of scarab beetle (3). Also said to take small vertebrates, located by gleaning foliage and litter. Overall, constituents of diet estimated to be fruits 70%, leaves 20%, invertebrates 5% and vertebrates 5% (6). Most feeding occurs between 09:00 hours and 17:00 hours (3). Forages singly , in pairs or in small groups of up to six in non-breeding season (with equal numbers of males and females) (3), but occasionally exceptional aggregations are recorded at fruiting trees, e.g. 40–50 in Belize at fruiting figs (3). Drinks at edges of streams or at waterholes (3).

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Vocal behaviour subject to detailed investigation in Costa Rica (7). Booming song, given only by males, consists of a deep, resonant and ventriloquial “oomp” note that is not very far-carrying, repeated every c. 10 seconds and used in two types of series, the first rendered “whooó-hoo-hoo”, the second “woo...woooó, hoo, woo... woo” in which the first pause lasts 2–3 seconds and the second five seconds (8). In Costa Rica, bouts of booming generally last 35 minutes, occasionally for up to five hours, and is heard between Feb and Jun, peaking in late Apr and early May, and discriminant analysis of boom calls of birds from ten different locations revealed inter-individual variation in call structure (7). Elsewhere, males mainly start singing c. 2 months before main breeding season and continue well into the female’s incubation period; peak daily vocalization activity is 05:00–07:00 hours, 09:00–13:00 hours and 15:00–17:00 hours; although nocturnal singing is recorded, no data exist to quantify its frequency (3). In alarm gives high-pitched “peep” notes that trail off or externallink , primarily given by males (7), while a captive female was reported to utter a soft, repeated “humm” and a louder “hoot, hoot” (8). Yip and bark calls are sex-specific alarm calls of very short duration (0·12 and 0·08 seconds, respectively). Also gives short snarl call (0·67 seconds) associated with threat display produced by adults with dependent young (7).

Breeding

Season Feb–May in mainland Mexico, just before rains; Feb–Jun on Cozumel I (3); incubating females found late Feb–early Jun in El Salvador, with peak Mar–Apr (3); Mar–May in Costa Rica; Feb–Mar in E Panama, during rains; two laying females in Mar in Chocó and NW Antioquia, Colombia. Considered monogamous, but polygamy possible (3). Pairs start constructing several different nests of which only one is completed (3). Nest sometimes relatively small and flimsy, but usually a more robust basket-shaped (3) structure (mean 37 cm long, 28 cm wide and 9 cm deep) (3) of sticks and lined with green leaves, placed in trees or large bushes (31 different species identified) (3) usually 4–9 m above ground (but overall range 3–23 m) (3) and often in close proximity to liana tangles (3); one nest was constructed entirely of green leaves. Lays two white (8) eggs, size 85–93·5 × 60–70·5 mm (3); incubation (in captivity) 28–32 days, in wild 33 days (3), with eggs always laid at sunset at two-day intervals (3); chicks greyish buff with black and chestnut markings above, whitish below, mass 123 g on hatching, 540 g at 30 days, 1250 g at 60 days, 1860 g at 90 days and 2500 g at 180 days (8). Small chicks may be carried by female when escaping perceived danger during first days of life (3). Long-lived; one female lived 24 years in captivity, and bred until 23.

Conservation Status

VULNERABLE. Overall population considered to number fewer than 40,000 individuals. Rapidly disappears wherever logging roads are built into previously inaccessible forests; thus extirpated from much of Veracruz, Mexico; on other hand, range recently revealed to be more widespread than previously known in Mexican Yucatán (9) and to encompass additional protected areas in the region (10). In Guatemala, still reported to be fairly common in E Caribbean lowlands, N Quiché and remote areas of Petén, but much reduced and threatened on Pacific slope, occurring in fragmented populations, particularly in Atitlán complex and S slopes of Volcanes Lacandón and Chiquibal. In El Salvador, species survives in El Imposible National Park, where population of at least 120 individuals in 1999 (3). Maintains stable populations throughout vast areas in Nicaragua. In Costa Rica, now mostly scarce and local, but can persist in secondary forest in absence of hunting (11), with good populations persisting mainly in some national parks, including Santa Rosa, Rincón de la Vieja and Corcovado. In Panama, remains only in remote, uninhabited areas, where still apparently fairly common, but disappears quickly, as settlement progresses; more widespread on Caribbean slope, while on Pacific slope perhaps limited to S Veraguas, W Azuero Peninsula, Darién (e.g. Serranía de Majé) (12), and parts of Canal Zone, where very rare; in 1979 good numbers still occurred in Barro Colorado I Biological Reserve, where well protected, but apparently extirpated from Chiriquí region. In Colombia, persists only in remoter areas and along Pacific coast, but never near roads. In 1986 species was feared completely eradicated from Ecuador, although it was still present in Guayas in 1970s (3), but today the species clings on only in far NW, in Esmeraldas (3) and may number < 100 individuals. Legally hunted in some countries. Race griscomi once feared extinct; in 1965, said to survive, although sometimes hunted; a male was seen around 1990 by a researcher after months of searching, but mid-1990s surveys suggest that population might still number c. 300 birds (4), with another estimate of 372 ± 155 individuals, before two hurricanes hit Cozumel in 2005; it has been suggested that a ban on hunting, eradication of feral fauna, particularly dogs, and implementation of a captive-breeding programme to supplement the wild population are needed to ensure this race’s survival (13). Nominate race quite common in captivity, where frequently bred; in Guatemala, small breeding programme initiated with aim of reintroducing species to areas where now extinct. One of cracids most commonly kept in captivity by locals: in Guatemala up to 100 live individuals, mainly young birds, estimated to be sold each year in local trade. CITES III in Guatemala, Costa Rica, Honduras and Colombia.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding