Adelie Penguin Pygoscelis adeliae Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (26)

- Monotypic

Text last updated April 20, 2017

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Bulgarian | Пингвин на Адели |

| Catalan | pingüí d'Adèlia |

| Croatian | adelijski pingvin |

| Czech | tučňák kroužkový |

| Dutch | Adéliepinguïn |

| English | Adelie Penguin |

| English (United States) | Adelie Penguin |

| Finnish | jääpingviini |

| French | Manchot d'Adélie |

| French (France) | Manchot d'Adélie |

| German | Adeliepinguin |

| Icelandic | Aðalsmörgæs |

| Japanese | アデリーペンギン |

| Norwegian | adeliepingvin |

| Polish | pingwin białooki |

| Russian | Пингвин Адели |

| Serbian | Adeli pingvin |

| Slovak | tučniak okatý |

| Slovenian | Adeli pingvin |

| Spanish | Pingüino de Adelia |

| Spanish (Argentina) | Pingüino de Adelia |

| Spanish (Chile) | Pingüino de Adelia |

| Spanish (Spain) | Pingüino de Adelia |

| Swedish | adéliepingvin |

| Turkish | Adeli Pengueni |

| Ukrainian | Пінгвін Аделі |

Pygoscelis adeliae (Hombron & Jacquinot, 1841)

Definitions

- PYGOSCELIS

- adelia / adeliae

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

The most difficult member of the genus to see in South America, the Adelie Penguin is decidedly Antarctic. Although it breeds on some sub-Antarctic islands, the bulk of the population breeds on various ice shelves and peninsulas on Antarctica. The species is highly pelagic and after breeding is very dispersive, with most adults moving north to rich feeding grounds and some occasionally reaching South America. This is by far the most studied species of penguin, and despite concerns of the negative impact of such intensive research, the population is stable or even growing. The Adelie is well known for its habitat of mounting icebergs to rest. Adelies also molt on ice floes, rather than in the breeding colonies, a strategy that is unique among penguins.

Field Identification

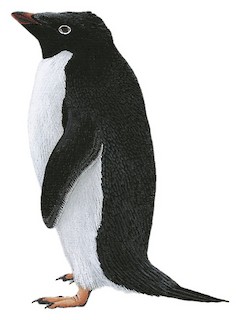

70–71 cm; 3·8–8·2 kg. Short-billed medium-sized penguin with long tail. Adult has entire head to upper throat and upperparts black with bluish sheen (sometimes blackish-brown), this extending to axillary area; flipper black with white trailing edge above, white to largely pinkish with blackish tip and narrow leading edge below, tail black; lowermost throat and entire underparts white; iris dark brown, conspicuous bare white orbital ring ; upper mandible reddish, with fuscous-red to black along most of culmen and sometimes also along cutting edge, lower mandible reddish with duskier cutting edge or largely fuscous-red to black with a little reddish at tip and base; legs pinkish, blackish soles and rear of tarsus. Rarely, entirely dark adults (with white orbital ring) have been reported, the underparts being hardly paler than the head; also, leucistic and other odd-coloured bird photos of an entirely white-plumaged bird known to occur. Sexes alike. Juvenile has chin and throat white, the blackish of lower head reaching not below malar area, cheek and ear-coverts, but sometimes chin also dark, and orbital ring and bill all dark at first.

Systematics History

Subspecies

Distribution

Circumpolar in S; largely restricted to Antarctica.

Habitat

Marine. Together with the Emperor Penguin, this is an 'ice obligate' species that associates with sea ice and its vicinity (1). It nonetheless breeds on snow and ice-free rocky coasts , tending to occupy higher ground than that selected by P. papua; often in extensive open areas to accommodate its typically large colonies. Colonies can be far from open sea but are typically associated with polynyas, which reduce the commuting time and energy expenditure involved in travelling between the colony and its food supply (1). Forages in inshore waters when breeding, and within the pack ice area when moulting and during the winter foraging period (2).

Movement

Dispersive. Unlike most other species, adults do not moult at colony but, rather, on ice floes; after breeding birds move N towards rich feeding grounds. Most immatures remain in zones of pack ice for at least 2 years, and sometimes 3–5, before returning to natal colony; immatures normally return to colonies later than adults, with delay of up to 2–3 months. In one satellite-tracking study, seven fledglings left the colony in Feb and travelled N, before turning W along edge of fast ice or in pack ice, and had moved between 536 km and 1931 km to W of natal colonies when transmission signals ceased; four adults tracked during Mar–Oct (post-moult) travelled W until Jul and then moved N within expanding pack ice into areas of high krill concentration, before returning E towards breeding sites; movements during winter months were closely related to movement patterns of sea ice, which were, in turn, influenced by oceanic currents and wind, and the researchers suggested that large gyral oceanic systems provide a means for penguins to reduce costs of transport as they move into regions of high productivity in winter and return to colonies in spring. (3) Accidental in South America, Falklands, Australia, New Zealand and several islands of Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Diet and Foraging

Mainly krill (Euphausia superba, Euphausia crystallorophias), with smaller quantities of fish, amphipods and cephalopods. In a study of stomach contents of 103 adults at Laurie I (South Orkneys) during three crèche periods (1989, 1990, 1992), euphausiids were predominant item in terms of frequency, mass and number, with fish and amphipods present in small amounts; Euphausia superba was the only species found in all samples; the only fish species identified was the myctophiid Electrona antarctica, and amphipods were Themisto gaudichaudii, Cyllopus lucassi, Hyperia, and unidentified gammariids. (4) Captures prey by means of pursuit-diving; recorded at depth of 175 m, but normally fishes no more than than 35 m down. May feed mostly by night. Studies at two widely separated sites, i.e. Béchervaise I (E Antarctica) and Edmonson Point (Ross Sea), revealed that sexes differed in foraging-trip duration, foraging locality and diet: differences in foraging behaviour most pronounced during guard stage of chick-rearing, when females undertook on average longer trips than males, ranged greater distances more frequently and consumed larger amounts of krill, whereas males made shorter journeys and fed more extensively on fish (and also took more fish throughout chick-rearing stage); during guard stage, mean foraging-trip duration over four seasons at Béchervaise I and over two seasons at Edmonson Point were 31–73 hours for females and 25–36 hours for males; at Béchervaise, 90% of satellite-tracked males during first three weeks after hatching stage foraged within 20 km of colony, whereas majority (60%) of females travelled 80–120 km from colony, to edge of continental shelf, to forage. (5)

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Very noisy at colony. Main call, in display, a loud rolling “aar-rar-rar-rar-raaah”, followed by “kuk-gu-gu-gu-gaaaa” , often given by partners at nest-site. Contact call a sharp, loud throaty bark, “aark” and variants . Also various growls and grunts in agonistic situations.

Breeding

Arrival at colony Sept–Oct, most laying in Nov. Colonial , on occasion forming enormous aggregations of many thousands of pairs ; sometimes nests beside congeners, but usually in discrete sectors; nests very close together. Nest a small depression lined with pebbles. Clutch 2 eggs ; replacement may be laid (but only 1 egg) if initial clutch lost; incubation by both sexes, period 30–43 days, with stints of 7–23 days (females sometimes take shorter initial shift); first down pale grey, much darker on head, second down sooty brown ; chicks form crèche at c. 16-19 days; fledging at 41–64 days, usually 50–56 days. Overall breeding success 50% at Cape Royds (Ross ice shelf, in Antarctica), 7·5–76·7% on Signy I (South Orkneys); on King George I (South Shetlands), breeding success (chicks in crèches/nests with eggs) fluctuated between 0·65 and 1·26 (very similar to figures for P. papua) (6). Sexual maturity reached by 8 years of age, possibly before, rarely at 5 years and exceptionally at 3. Presence of Chinstrap Penguins has been found to depress breeding success of Adelie Penguins where the two species form mixed colonies: 32% of Adelie nests were usurped by Chinstraps in one study in the western Antarctic Peninsula (7).

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). In 2012, listed for the first time as Near Threatened by BirdLife International based on research indicating that northern colonies could be lost due to projected climate change (1). However, at present numbers are increasing in the Ross Sea region and decreasing in the Peninsula region, with the net global population increasing overall (1, 8). A first global census, achieved using a combination of ground counts and satellite imagery, has recently found a breeding population of 3·5–4·1 million breeding pairs (9), 53% larger than that estimated in 1993 (10). The recent, post-2010, census found that although eight colonies have gone extinct 17 previously unknown colonies were detected and declines on the Antarctic Peninsula have been more than offset by increases in East Antarctica (11, 12). It was therefore downlisted to Least Concern in 2016. This is much the most studied penguin. Total of at least 1,100,000 pairs in Ross Sea sector, where largest colony at Cape Adare, with c. 282,307 pairs; at least 177,000 pairs at Cape Crozier. Installation of scientific stations near colonies has caused serious problems, with limitation of suitable ground for breeding, excessive frequency of visits to colonies, helicopters flying overhead, etc. In Ross Sea sector, census figures reveal that number of breeding pairs has decreased in the past; population at Cape Royds comprised 1500–2000 pairs during 1907–1956, but, following establishment of base at McMurdo Sound, declined to 1100 pairs in 1962; although small numbers were still killed annually at this site, for scientific purposes, a general decrease in human interference thereafter resulted in recovery to 3986 pairs; in 1916, collection of 2400 eggs at Cape Royds virtually eliminated colony. Enlargement of base on Petrel I (in Adélie Land) also led to decrease in breeding numbers. At Cape Hallett, a colony of 8000–10,000 pairs was evicted for the construction of research station. In a long-term study of a colony at King George I, in South Shetlands, a population decrease of 62% was recorded between the 1995–1996 and 2006–2007 seasons, this accompanied by a similar decrease in number of chicks in crèches (smallest number in 2002, when 63% fewer than in 1995–1996), whereas P. papua population increased by more than 60%; these two species were very similar in breeding success, which suggests that the differing population trends were result of factors operating in winter period, such that juvenile survival (and thus recruitment of new breeders) of present species might be much lower (6). Apparently very few colonies have increased (e.g. Haswell I), whereas most undisturbed colonies stable. Increase in tourist visits to some colonies liable to have detrimental effects. Some birds found oiled on Ross I; an increase in shipping traffic would clearly have negative effects. Problems facing this and other penguin species also include proximity of scientific bases and disturbance caused by helicopters flying over colonies, although disturbance caused by survey helicopters considered negligible if flights conducted with due care (13).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding