Baird's Sparrow Centronyx bairdii Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (20)

- Monotypic

Text last updated January 1, 2002

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Catalan | sit pardalenc de Baird |

| Dutch | Bairds Gors |

| English | Baird's Sparrow |

| English (United States) | Baird's Sparrow |

| French | Bruant de Baird |

| French (France) | Bruant de Baird |

| German | Bairdammer |

| Icelandic | Kjaltittlingur |

| Japanese | バードヒメドリ |

| Norwegian | dakotaspurv |

| Polish | bagiennik łąkowy |

| Russian | Прерийная овсянка-барсучок |

| Serbian | Berdov strnad |

| Slovak | strnádlik samotársky |

| Spanish | Chingolo de Baird |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Gorrión de Baird |

| Spanish (Spain) | Chingolo de Baird |

| Swedish | präriesparv |

| Turkish | Baird Serçesi |

| Ukrainian | Багновець польовий |

Centronyx bairdii (Audubon, 1844)

Definitions

- CENTRONYX

- bairdi / bairdii

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

“During one of our Buffalo hunts, on the 26th July, 1843, we happened to pass along several wet places, closely over-grown by a kind of slender rush-like grass, from which we heard the notes of this species, and which we thought were produced by Marsh Wrens ( Troglodytes palustris ), and my friends [Edward] Harris and John G. Bell immediately went in search of the birds. Mr. Bell soon discovered that the notes of Baird's Bunting were softer and more prolonged than those of the Marsh Wren. They had much difficulty in raising them from the close and rather long grass, to which this species appears to confine itself; several times Mr. Bell nearly trod on some of them, before the birds would take to wing, and they almost instantaneously realighted within a few steps, and then ran like mice through the grass. After awhile, however, two were shot on the wing, and both fortunately were found, and proved to be an adult male and female. We found this species abundant in all such situations as I have mentioned above, and doubtless it breeds in them." -- (Audubon 1844: 359).

Audubon's 2 specimens—from “Wet portions of the prairies of the Upper Missouri,” (p. 359) this location determined to be near Old Fort Union (Williams County), North Dakota—were the first scientific record of this species. The last bird species described by Audubon, this sparrow was the first of several bird species named for Spencer Fullerton Baird, another of America's great nineteenth-century ornithologists. It was not recorded again for 29 years, when another specimen was taken in Colorado, and in 1873 Elliott Coues (Coues 1874a) rediscovered the species in abundance on its North Dakota breeding grounds, and its first nest was found (Allen 1874). Now, Baird's Sparrow is considered a defining feature of summer bird life for mixed-grass and fescue prairies of the northern Great Plains of North America. Its clear song, unique among songs of other Ammodramus species, gives one an indication of being in or near high-quality prairie. Early in the breeding season, males frequently sing at or near the tops of high grass clumps or scattered shrubs in their territory and are not difficult either to locate or approach. When necessary, however, they maneuver through the grass and elude even the sharpest-eyed observer.

Once considered among the most common of prairie birds, Baird's Sparrow is now rare throughout its range and only locally abundant depending on the condition of grasslands. Agriculture has eliminated much of its former range and continues to reduce remaining grassland tracts. Areas of potentially suitable prairie can become unsuitable when overgrown with woody or exotic vegetation because natural patterns of fire and grazing are lacking. This species was formerly thought an exclusive denizen of native grasses, but recent research reveals an acceptance of formerly cultivated lands with structural components resembling native prairie, and in agriculatural use such as hayfields or pastures with strong incursions or plantings of non-native grasses. Actively cultivated lands, while used to some degree, are clearly unproductive for this species, however, and are likely responsible for population declines in this and several other grassland species.

Fitting the pattern of some other grassland birds, Baird's Sparrow appears partially nomadic, sometimes exhibiting dramatic shifts in population densities from one year to the next. Such behaviors are likely an evolved response to shifting habitat suitability due to the unpredictable but common influences of fire, drought, and the movements and grazing of bison (Bison bison) herds.

The first comprehensive study of the breeding biology of this species was conducted by 3 amateur ornithologists—B. W. Cartwright, T. M. Shortt, and R. D. Harris—near Winnipeg, Manitoba (Cartwright et al. 1937): In 3 years, they found 15 nests and made observations of activities at 3 nests from blinds. Until the work of Cartwright and others, published information on Baird's Sparrow consisted mostly of scattered descriptions of summer or winter occurrence, or song. Oologist E. S. Rolfe remarked that, in 12 seasons, he had been able to find only 3 nests, even though he regarded this species as “common” (Rolfe 1896a). Recent focus on declining populations of grassland birds has prompted research on habitat requirements, abundance, distribution, and breeding biology of Baird's Sparrow throughout its breeding range (Dale 1983, Desmet and Conrad 1991, Green 1992b, Davis 1994b, Winter 1994, Mahon 1995, Skeel et al. 1995, Madden 1996, Dale et al. 1997, Davis and Sealy 1998). The distribution and biology of Baird's Sparrow on its wintering grounds are still poorly understood and little studied, but this species has been included in studies of wintering sparrows in Arizona (Gordon 2000b).

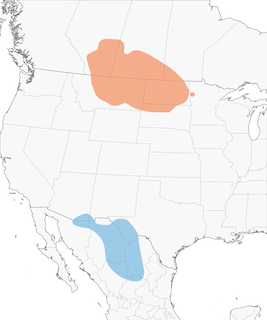

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding