Black-browed Albatross Thalassarche melanophris Scientific name definitions

Text last updated January 2, 2018

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Swartrugalbatros |

| Asturian | Albatros esgoyerñu |

| Basque | Albatros bekainduna |

| Bulgarian | Черновежд албатрос |

| Catalan | albatros cellanegre |

| Croatian | žutokljuni albatros |

| Czech | albatros černobrvý |

| Danish | Sortbrynet Albatros/Campbell Albatros |

| Dutch | Wenkbrauwalbatros |

| English | Black-browed Albatross |

| English (New Zealand) | Black-browed/Campbell Mollymawk |

| English (United States) | Black-browed Albatross |

| Faroese | Dimmbrýntur súlukongur |

| Finnish | mustakulma-albatrossi |

| French | Albatros à sourcils noirs |

| French (France) | Albatros à sourcils noirs |

| Galician | Albatros olleirudo |

| German | Schwarzbrauenalbatros |

| Greek | Μελανόφρυδο Άλμπατρος |

| Hebrew | אלבטרוס שחור-גבות |

| Hungarian | Dolmányos albatrosz |

| Icelandic | Svaltrosi |

| Italian | Albatro sopracciglineri |

| Japanese | マユグロアホウドリ |

| Lithuanian | Siauraakis albatrosas |

| Norwegian | svartbrynalbatross |

| Polish | albatros czarnobrewy |

| Portuguese (Angola) | Albatroz-olheirudo |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | albatroz-de-sobrancelha |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Albatroz-de-sobrancelha |

| Romanian | Albatros cu sprânceană neagră |

| Russian | Чернобровый альбатрос |

| Serbian | Albatros crnih obrva |

| Slovak | albatros čiernobrvý |

| Slovenian | Falklandski albatros |

| Spanish | Albatros Ojeroso |

| Spanish (Argentina) | Albatros Ceja Negra |

| Spanish (Chile) | Albatros de ceja negra |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Albatros Ojeroso |

| Spanish (Panama) | Albatros Cejinegro |

| Spanish (Peru) | Albatros de Ceja Negra |

| Spanish (Spain) | Albatros ojeroso |

| Spanish (Uruguay) | Albatros Ceja Negra |

| Swedish | svartbrynad albatross/campbellalbatross |

| Turkish | Kara Kaşlı Albatros |

| Ukrainian | Альбатрос чорнобровий |

Thalassarche melanophris (Temminck, 1828)

Definitions

- THALASSARCHE

- melanophris / melanophrys

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

Taxonomic note: Lump. This account is a combination of multiple species accounts originally published in HBW Alive. That content has been combined and labeled here at the subspecies level. Moving forward we will create a more unified account for this parent taxon. Please consider contributing your expertise to update this account.

The Black-browed Albatross is a robust mollymawk, a popular name for smaller albatrosses in the genus Thalassarche. The white head, dark back, and orange-tipped yellow bill of adults are diagnostic and recall a large, dark-backed gull. This species often feeds in the company of other seabirds, sometimes following boats or cetaceans. It is more frequent close to shore than other seabirds, often coming into harbors or bays and once even was observed feeding on a lake 35 km inland in Tierra del Fuego. Pairs nest annually in large colonies, using a large nest of mud and grass placed on the ground.

Field Identification

Black-browed Albatross (Black-browed)

79–93 cm (1); male 3266–4658 g, female 2840–3806 g (2); wingspan 205–240 cm. Heavy build; wings often appear broad and blunt; fairly dark underwing, with variable white central stripe; black patches on underwing at carpal joints can be more or less evident. Adult has all-white head and neck except diffuse black mark of variable extent just before and behind eye, the white lowermost hindneck fades into dark greyish mantle and back, scapulars and upperwing similar to back but usually darker, blackish, becoming dark brown in worn plumage, shafts of outer primaries white, rump and uppertail-coverts white ; tail grey; the dark margins on underwing are broad, especially on leading edge, with some dark marks on carpal area; underparts white; iris very dark, with narrow black orbital ring; bill pale orange-yellow with variable pinkish wash, deeper and brighter pinkish or orange at tip, very thin black line at bill-base visible at close range, gape sometimes visible as pink line on foreface; legs pale bluish grey with variable amount of pale pinkish areas. Sexes similar, but male typically larger, although only bill depth, head width and nape can accurately be used to discriminate the sexes (3). Underwing pattern recalls that of Phoebastria immutabilis (geographical overlap unlikely), but can be separated from latter by white rump, bare-part colours, and by feet not projecting beyond tail-tip. In Atlantic, T. chlororhynchos has relatively longer, more slender bill, narrower wings (which are always white with black leading edge), mostly black bill (with yellow culminicorn ridge and reddish tip) and smoky grey head and neck (1). T. chrysostoma (much overlap in Southern Ocean) averages slightly stockier, but distinctive grey head and neck, and largely black bill of adult mean that only real confusion is between young of two species, when best to concentrate on bill pattern (chrysostoma lacks darker tip, being blackish to black with perhaps a trace of yellow culminicorn and ramicorn stripes, and has diagnostic broad, wedge-shaped naricorn, although this will only be visible at close range) (1). T. cauta is larger and bigger-billed than present species, and usually has paler bill, greyish with more contrasting black tip, while underwing pattern is characteristically different, white with narrow black margins (1). Juvenile (and first-year) (4) resembles adult, but bill blackish horn or dusky brown with black tip, becoming gradually paler with age, the tip and base of upper mandible are often the last dark areas when plumage already adult-like; underwing has no white , the coverts being dark brownish grey; hindneck and uppermost mantle possess obvious but variable brownish-grey tinge forming diffuse area that often extends to pectoral band, frequently more clear-cut forming a partial collar not reaching foreneck. Second-year has obvious grey collar, black eyebrows, develops pale panel on underwing and first yellow appears on bill, along culminicorn ridge; third-year has short eyebrows, greyish wash to hindneck and underwing has usually whitened further (but still variable), while bill is very variable, from mostly dark to pale yellowish with dark tip (4); by age four the eyebrows and collar have all but disappeared, the bill is yellowish with black tip, and underwing pattern is almost adult-like (5), while five-year-old shows neat black eyebrows, sometimes has greyish cheeks and hindneck, and bill is basically adult-like with grey wash to lateral and distal horny plates, and by age six birds are not safely distinguishable from adults (4, 6). However, while moult pattern can be useful for ageing birds, it should be noted that birds that “switch” hemispheres can apparently adjust their moult cycle to that of the Northern Hemisphere (7). Leucistic individuals (both adults and young) have been recorded in S Atlantic (8).

Black-browed Albatross (Campbell)

88–90 cm (9); male 2750–3800 g, female 2200–3150 g (2); wingspan 205–240 cm. Medium-sized, black-and-white albatross with black triangle around eye that reaches base of bill. Adult has white head , neck, rump, underparts , with black upperwing , back and tail , white underwing with broad black edges ; yellow bill , becoming orange at tip. Juvenile has brown-grey bill with black tip, dark eyes, a partial or complete band extending from mantle around chest, and more extensive black on underwing. Compared to <em>T. melanophris</em> , with which this species was formerly regarded as conspecific, <em>impavida</em> has pale iris , ranging from whitish to amber, underwing tends to be more extensively dark, especially at base, the black “eyebrow” is usually larger and “heavier”, and a diffuse grey wash is visible on cheeks. Averages smaller than T. melanophris in culmen, tarsus, wing and tail measurements (9). No known differences in plumage maturation from T. melanophris and differentiated from other potential confusion species based on similar characters as listed for the latter.

Systematics History

Editor's Note: This article requires further editing work to merge existing content into the appropriate Subspecies sections. Please bear with us while this update takes place.

Black-browed Albatross (Black-browed)

Until recently considered conspecific with T. impavida (which see). Genetic studies indicate that form breeding in Falkland Is represents a separate taxon (10), as yet unnamed. Specific name sometimes listed as melanophrys but this is an incorrect subsequent spelling and has been formally suppressed (11). Monotypic.Black-browed Albatross (Campbell)

Until recently considered conspecific with T. melanophris, but differs in its pale vs dark eye (3); generally greyer face (1); reduced area of white on underwing, forming relatively narrow white line within black (1); smaller size with a relatively shorter bill, published data (12) indicating effect size 4.09 (2) yet slightly longer tarsus (effect size 1.33, score 1) and considerably lighter weight (13). Genetic analyses support treatment of impavida as a distinct species (10). Evidence of sympatric breeding with T. melanophris (14) is inconclusive, amounting to mixed pairs reported on Campbell I (15, 13). Monotypic.Subspecies

Black-browed Albatross (Black-browed) Thalassarche melanophris melanophris Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Thalassarche melanophris melanophris (Temminck, 1828)

Definitions

- THALASSARCHE

- melanophris / melanophrys

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Black-browed Albatross (Campbell) Thalassarche melanophris impavida Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Thalassarche melanophris impavida Mathews, 1912

Definitions

- THALASSARCHE

- melanophris / melanophrys

- impavida / impavidus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Hybridization

Hybrid Records and Media Contributed to eBird

-

Gray-headed x Black-browed Albatross (hybrid) Thalassarche chrysostoma x melanophris

Distribution

Black-browed Albatross (Black-browed)

Southern Ocean, breeding from Cape Horn and Falkland Is E to Antipodes Is.

Black-browed Albatross (Campbell)

Subtropical to Antarctic S Pacific Ocean, breeding on Campbell I (S of New Zealand).

Habitat

Black-browed Albatross (Black-browed)

Marine ; to some extent pelagic , wandering over vast areas of sea sometimes 1000s of km from land , but also commonly near shore; more common on inshore waters than other albatrosses, being a common inhabitant of the comparatively enclosed waters of the Beale Channel (16), and entering fjords, bays and harbours, especially in stormy weather; even recorded feeding c. 35 km inland on freshwater lake at Tierra del Fuego; often feeds over continental shelf or shelf slope. Breeds on remote oceanic islands , normally on steep slopes with tussock grass; sometimes on cliff terraces, but also in muddy drainage lines on Gonzalo I in Diego Ramírez archipelago (Chile) (17).

Black-browed Albatross (Campbell)

Much as for T. melanophris.

Migration Overview

Black-browed Albatross (Black-browed)

Despite extensive ringing, until recently movements not very well understood. However, Black-browed Albatrosses from different breeding areas have distinct winter foraging zones, with birds from Falkland Is foraging off E coast of South America, while those from South Georgia forage off W South Africa (18), and such differences can even extend to different colonies on the same group of islands, e.g. on Kerguelen I and the Falklands birds from different colonies on same island forage over different parts of surrounding continental shelf (19). During incubation period on Falkland Is, satellite tracking reveals sexes forage in different areas with almost no overlap, while during chick-rearing, breeding birds initially stay in shelf/shelf-slope areas near colonies (within c. 500 km), but later those from South Georgia may travel up to c. 3000 km, especially to Antarctic Peninsula and South Orkney Is, while those from Falklands and Kerguelen continue to remain relatively close to their colonies. Post-breeding, strong migratory movement N in South Atlantic populations, with young from different breeding grounds showing distinct target areas; perhaps also adults; birds from Falklands move to coast of E Brazil (20), recovered as far N as Sergipe, NE Brazil (21), but South Georgian birds probably also winter in these waters to some extent (20). Off Victoria, S Australia, birds from both Kerguelen and South Georgian colonies have been recovered, although bulk of birds foraging in these waters assumed to be Macquarie I breeders (22). Birds from South Georgia predominantly migrate to S African waters, spending first half of winter in highly productive Benguela Current; for this population, at least, studies have revealed that initiation of outward migration varies according to breeding status, timing of failure, and sex: deferring breeders and those that fail early depart two months before successful birds, and successful females depart 1–2 weeks earlier than males, while sex-related latitudinal variation in distribution is also apparent, with females wintering further N in the Benguela system (23). Those breeding in Chile concentrate over Chilean Shelf, Patagonian Shelf, and some spend non-breeding season around N New Zealand; nevertheless, satellite-tracking of birds breeding on an island in Diego Ramírez group revealed magnitude of some foraging trips, with birds ranging from 36° S to Antarctic waters at 67° S, with each trip covering 1000–7700 km (24). In this part of Southern Ocean, also recorded S into Ross Sea (25). New Zealand breeders move E to waters off S South America (26). The commonest straggler of all albatrosses into N Atlantic, with 41 records for Britain alone up to 1985; also recorded off Germany (1988) (27), Norway (1979, 1987, 1989, 1990) (27), Faeroe Is, Spitsbergen, Franz Josef Land (28), the SE Barents Sea (2007) (29), Sweden (1990) (27), Iceland (1966 and 1987) (27), and has even entered Mediterranean, off Corsica (Feb 1991) (30) and W Italy (Jul 2000) (31); less common in NW Atlantic (mainly Jun–Oct) (1), where T. chlororhynchos more regularly recorded, but has still been sighted N to Labrador, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia and even W Greenland (1). In contrast and perhaps surprisingly, rarely seems to penetrate far N in Pacific and Indian Oceans, e.g. is considered only a vagrant (mainly in Jun–Sept) in Malagasy waters (32), in SW Indian Ocean, although has been recorded N to Kenya (Jun, Sept, Oct) (33). Tradition of its capture as mascot for fishing vessels may have produced some of N Hemisphere records in past; nowadays, in some regions banded birds may be deliberately killed out of curiosity (26). Inland records are decidedly uncommon, but has been claimed up to 75 km from coast in Chile, although there appears to be some doubt if the identification can be proven in this case (34).

Black-browed Albatross (Campbell)

Range at sea of young T. impavida probably concentrated on S Australian waters, the Tasman Sea and temperate SW Pacific (2) (ranging N to Vanuatu, Fiji and Tonga) (35), while breeding adults forage from South I, New Zealand, and Chatham Rise S towards Antarctica: satellite-tracking revealed that birds provisioning chicks predominantly forage over neritic waters during trips of < 4 days, with longer trips of 8–21 days over oceanic waters; foraging range during short trips was 150–640 km from the colony, mainly over subantarctic waters within the 1000 m depth contour on Campbell Plateau, although longer trips reached up to 2000 km (36), ranging from subtropical to Antarctic waters, but mainly to Polar Frontal Zone or E of Campbell Plateau (37).

Diet and Foraging

Black-browed Albatross (Black-browed)

Mainly crustaceans (Euphausia superba, Themisto gaudichaudii (38), Munida, Gnathophausia gigas, Pasiphaea longispina, Eurythenes spp.) (39) and fish (especially Myctophidae and Nototheniidae (38), species include Ctenosciaena gracilicirrhus (40), Champsocephalus gunnari, Magnisudis prionosa (41), Patagonotothen guntheri, Icichthys australis (38), Prionotus punctatus (42), Micropogonias furnieri, Paralonchurus brasiliensis, Macrodon ancylodon, Urophycis brasiliensis, Porichthys porosissimus (43), Geotria australis) (44); also squid, octopuses and other molluscs (especially Cranchiidae and Onychoteuthidae (45), species include Todarodes filippovae (39), T. sagittatus, Lycoteuthis lorigera (40), Loligo gahi (19), L. sanpaulensis, Ancistrocheirus lesueurii, Octopus vulgaris, Haliphron atlanticus, Ocythoe tuberculata (43), Moroteuthis knipovitchi (45), Galiteuthis glacialis) (38), fishery discards (species frequently follows boats) (2), insects (Coleoptera) (40) and carrion, e.g. penguin corpses (which constitute 14% by mass of diet in Kerguelen Is) (2), and diving-petrels (Pelecanoides sp.) (42), a tern, probably South American Tern (Sterna hirundinacea) (42) and a Wilson’s Storm-petrel (Oceanites oceanicus) (46) have also been found in stomach contents of an albatross taken as bycatch. The importance of fishery discards is well illustrated by the example of a major trawl fishery for Loligo squid in the Falklands, in which waste amounts to c. 5% of the reported catch and just over 50% of this waste, mainly Loligo and nototheniid fish, is scavenged by adult albatrosses, with the total quantity scavenged during chick-rearing amounting to 1000–2000 tonnes per year, or 10–15% of the total requirements of the breeding population on Beauchêne I during the period when the fishery operates (19), while a wider study in the same archipelago, covering fisheries of hake (Merluccius spp.), hoki (Macruronus magellanicus), red cod (Salilota australis) and others, found that the species obtains c. 8000 tonnes of food per annum from this source—two-thirds offal and the remainder whole discards—with an energy content equivalent to 4·4% of the estimated total annual requirements of the Falklands melanophris population (47). Elsewhere, regularly observed attending trawl vessels targeting Argentine red shrimp (Pleoticus muelleri) off S Argentina (48). However, more recent research has demonstrated that birds from colonies in comparatively close proximity may show marked differences in their propensity to forage around trawlers, with only a small number of individuals repeatedly following fishing vessels, perhaps indicating that they specialise on fisheries resources (49). In one study, mean estimated total length and body mass of fish ingested by this species were 246 mm and 164·7 g, respectively (43), and typically scavenges larger discards than other regular attendees, such as Kelp Gulls (Larus dominicanus), at trawlers off Argentina (50). At South Georgia, between 1977 and 1995, chicks fed 13–37% squid (by mass, especially Martialia hyadesi) (38), 5–42% krill (mainly larger and sexually active females) (51) and the remainder in fish (28–72%) (38); considered a krill specialist at South Georgia, with birds dispersing further offshore when krill scarce (52) with result that foraging trips may double in length (41). Interannual variations can be significant, e.g. at South Georgia, cephalopods were most important dietary component in 1996 (49% by mass) and 1997 (48%), fish in 1998 (32%) and 1999 (40%), and crustaceans in 2000 (63%) (53). Falklands birds take only small quantities of crustacea, being mainly reliant on squid and fish (2). Captures prey mainly by surface seizing, but sometimes by means of pursuit plunging (from up to 9 m above the surface and reaching up to 4·6 m below surface) (2), surface plunging (mainly for krill or dead fish) (44) or surface diving, aided by the species’ amphibious optical design, wherein on immersion in water the eyes’ monocular fields decrease in width such that the binocular fields are abolished (54); probably forages both day and night (2), but mainly diurnally (39). Recent studies at South Georgia reveal that during incubation period, the sexes use different foraging areas and that these are also independent of those used by either sex of T. chrysostoma, which shows similar level of segregation during this period of life cycle (55). Feeds extensively on large swarms of krill and attends trawlers for discarded fish and squid. Often feeds in company of other Procellariiformes and other seabirds, including penguins (Eudyptes, Pygoscelis), gulls (Larus) and skuas (Catharacta), and off South Georgia (where this species serves as visual cue to presence of food) (56) it appears to initiate and dominate feeding frenzies at large patches of krill (57); off Chile steals fish from surfacing shags (Phalacrocorax); sometimes follows cetaceans (Balaena, Globicephala, Lissodelphis, Physeter (58) and Orcinus) (59) and feeding association also noted with Antarctic fur seal (Arctocephalus gazella) (57).

Black-browed Albatross (Campbell)

Thought to be largely similar to T. melanophris but few specific data appear to have been published, other than the comment that breeding T. impavida principally target schools of juvenile southern blue whiting (Micromesistius australis) or the squid Martialia hyadesi (9).

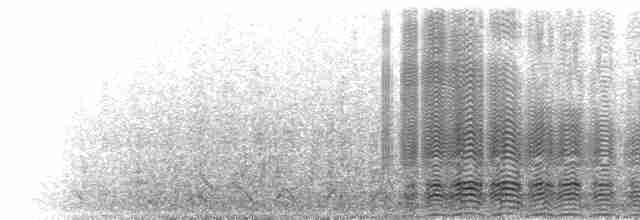

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Black-browed Albatross (Black-browed)

Principal calls are Croaks (which signal identification and possession) and Wails (latter often given in flight) (2).

Black-browed Albatross (Campbell)

Subtle differences in vocalizations between T. melanophris and the present species reported, but not thoroughly detailed (60).

Breeding

Black-browed Albatross (Black-browed)

Annual (although only 75–80% of successful breeders and 67–75% of failed breeders attempt to breed in following year (2) and 5–10% in both categories may delay a further year) (61), starting early Sept/Oct (2), when birds return to colony, followed by pre-laying exodus of c. 10 days (at least in females), thereafter well-synchronized laying extends over c. 20 days (typically 19–27 Oct (2), with eggs hatching mainly in first half of Dec and fledging in late Apr (2). Highly colonial ; large nest of mud , grass and roots, 30–33 cm wide at top of mound and spaced at 90–110 cm in New Zealand colonies (62). Reported breeding with T. cauta steadi on Antipodes Is (62); lost individuals in NE Atlantic have returned for many years to, and even built nests within, colonies of Northern Gannets (Morus bassanus) (1). Clutch single white egg , mean size at South Georgia 104 mm × 66 mm, 257 g (2); incubation 66–71 days, exceptionally 76 and 80 days (63), with male taking first long shift of c. 15 days and thereafter shifts become shorter (2) (lasting 1–8 days, mean four days) (64); chicks have greyish-white down , brooded for 1–4 weeks, fed on average every 1·22 days (each meal being c. 570 g) (65), and parent visits nest on average once every 2·07 days (65); fledging c. 116 days (65), usually at weight of 2500–3500 g (maximum weight is typically achieved at c. 90 days and is 4000–5000 g) (65); compared to chicks of T. chrysostoma, melanophris chicks on South Georgia grow at faster rate and to higher peak mass, achieving peak mass at an earlier age and losing weight faster during mass recession period) (66). Young that hatch later in season or during years when food availability is lower tend to be left alone by parents at earlier age and for longer periods, while weather changes may also impact brood-guarding, while individual pairs display some degree of inter-annual consistency in brood-guarding duration and, at least in certain years, longer brood-guarding results in higher fledging probability (67). Mean breeding success of melanophris on Macquarie I (Australia) c. 50% (± 8·5%, over seven years) (68), on South Georgia highly variable, but averaging just 27% (62% of eggs hatch and 43% of chicks fledge) (2). In 1959–1964 survival of fledglings from South Georgia to breeding age was 22–27%, but fell to just 11–14% in 1976–1981 and a mere 4–5% in 1982–1986 (2); breeding success at Heard I similar to that at South Georgia, but is higher on Macquarie I (69) and was much higher (51·6–61·6%) at one colony on the Falklands in late 2000s (70). Eggs and smaller chicks may be predated by Brown Skuas (Catharacta antarctica) (63), the latter hunted co-operatively (71). Chicks heavily infested by Ixodes uriae ticks less likely to survive to fledging (2), and breeding success also much reduced (by up to 90%) when icefish (Champsocephalus gunnari) (53) and krill scarce (41); around Kerguelen, breeding success strongly correlated with oceanographic conditions, especially sea surface temperatures, with poor breeding success related to presence of colder waters in main foraging zones (72); first-time breeders appear to be poorer performers compared to experienced adults, with lower reproductive success and lower survival, while survival probability varies with experience and climate, and differences are greater under harsh conditions, although it is nevertheless the case that reproductive success of inexperienced individuals is affected by climatic fluctuations just like experienced ones (73). Additional studies have shown that peripheral breeders within a colony perform considerably less well than do core breeders, irrespective of their experience, and timing of failure is affected by nest position, with peripheral nests significantly more likely than core nests to fail during chick rearing, with the main cause of failure being predation, because Brown Skuas and giant petrels (Macronectes spp.) both appear to target nests at periphery of colonies (74). Work has shown that individuals born to genetically dissimilar parents tend to produce greater than average numbers of young (75) . Sexual maturity at 7–9 years, with age of first breeding ranging between eight and 12 years (mean ten) (2); immatures begin to return to land at age two, with numbers of returning birds increasing up to age six (2); show strong natal philopatry, but birds sometimes “swop” sites, with birds from Macquarie found breeding on Campbell and one from Kerguelen bred on Heard (69). Adult mortality c. 7% per year (e.g. mean adult survival probability 0·942 on New I, Falklands, in 2003–2009) (76); known to have reached at least 34 years old (a bird that returned to the Faeroes annually until 1894). With increasing evidence for environmental effects on demographic traits, overall there is tendency for traits to improve during first years of life (5–10 years), to peak and remain stable in middle age (10–30 years) and decline during old age; when young, survival and reproductive parameters increase, except offspring body condition at fledging, suggesting that younger parents have already acquired good foraging capacities, but their inexperience results in higher breeding failures during incubation; while there is also evidence for reproductive and actuarial senescence as, in particular, breeding success and offspring body condition decline abruptly suggesting changed foraging capacities in older birds (77). In the Falkland Is, there is a curious example of a pair of albatrosses adopting a c. 20-day-old Rockhopper Penguin (Eudyptes chrysocome) chick for a two-day period, while also feeding their own young (78).

Black-browed Albatross (Campbell)

Annual, starting from early Aug (2), when birds return to colony, followed by pre-laying exodus of c. 10 days (at least in females), thereafter well-synchronized laying extends over c. 15 days (typically 24 Sept–8 Oct) (2), with eggs hatching mainly in first half of Dec and fledging in late Apr (2). Highly colonial ; large nest of mud , grass and roots. Colonies frequently mixed with T. chrysostoma (60). Clutch single white egg, mean size 102·6 mm × 66·1 mm (2); incubation 68–72 days (2), with male taking first long shift; chicks have greyish-white down, brooded for 1–4 weeks, fed on average every 0·97–1·08 days (averaging 393–474 g per feed) (2); fledging c. 130 days (2), usually at weight of 2500–3500 g (maximum weight is typically achieved at c. 90 days and is 4000–5000 g) (65). Mean breeding success on Campbell I was 67·8% (range 51–83%, over six years) (60). Survival of fledglings to breeding age is c. 18% (79), while 83% of successful breeders and 74% of failed breeders return to nest the following season (2). Sexual maturity at 6–13 years, mean ten (79); immatures begin to return to land at age five (2). Adult mortality c. 5·5% (79).

Conservation Status

Black-browed Albatross (Black-browed)

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). Probably most abundant and widespread albatross, with population previously estimated 550,000–600,000 breeding pairs, or 2,200,000–2,400,000 birds, and even higher, at 680,000 pairs, in 1998, of which 80% on Falklands (especially on Steeple Jason I, which colony had 196,600–232,700 nests in 1987) (80), 10% on South Georgia and 3% in Chile; however, more recent data revised this total to c. 575,151 pairs—70% in the Falklands (with numbers apparently increasong on Steeple Jason I by 2008) (70), 10% on South Georgia (c. 74,300 pairs in 2004) (81) and 20% in Chile (where there were c. 55,000 pairs on the Diego Ramírez archipelago alone in 2002) (82). Falkland Is hold c. 400,000 pairs, where numbers apparently increased substantially during 1980s, but thereafter declined at rate of 0·7% per annum (although some colonies have increased in size, trends are inconsistent between years and sites, and even between subcolonies within sites; 74,296 pairs on South Georgia (where adult survival decreased from 93% pre-1970 to 89% in 1987, and breeding success slumped over same period, from 36% to 18%); 114,608 pairs on islands of S Chile (just 85,000 pairs were estimated to occur there in 1980s) (83); Heard I (where colony discovered 1947) (69) and McDonald Is hold 600–700 (in 1987–1988) (69) and 82–89 pairs respectively, both colonies apparently on increase; first bred at Macquarie I in 1949/50, where population currently numbers 600–700 pairs and numbers considered stable since mid 1970s (84); elsewhere in SW Pacific region, single pair on Snares Is (1984 and 1995) (85) and 115 pairs on Antipodes Is (in 1994–1995) (86). Main cause of mortality probably incidental takes at commercial fishing grounds, e.g. at Kerguelen where population in decline, and South Georgian birds wintering off S Africa; competition with fisheries also potentially significant, e.g. krill fishing in Scotia Sea and squid fishery off Falkland Is; analysis suggested that the biomass of Antarctic krill within the largest size class was sufficient to support predator demand in the 1980s, but this was no longer the case by the decade following (87). Small numbers may be caught by fishermen for fish bait or to be kept as pets off S Africa and South America, but major declines associated with increased longline fishing for species such as Patagonian toothfish (Dissostichus eleginoides) (88), kingclip (Genypterus blacodes) (89), southern bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) (90), hake (Merluccius australis) (91) and ling (Genypterus blacodes) (24) and development of new fisheries over much of Patagonian Shelf (where this species formed > 55% of total bycatch in 1999–2001) (89), around South Georgia, off S African coast (91) and elsewhere in Southern Ocean (e.g. in 1990s Brazilian longliners were estimated to be taking > 900 individuals per year as bycatch) (92), with this albatross among the most frequently killed pelagic seabirds (e.g. three-year study in Australian Fishing Zone of bycatch taken by Japanese longliners found that 78% of total seabird bycatch was albatrosses, with T. melanophris and T. cauta caught in greatest numbers) (93); capture rates can vary greatly according to season, number of hooks and type of longline, but an estimated minimum of 5000 birds/year are killed by the deep-water hake trawl fishery in S African waters during winter (91), with evidence of a sex bias towards females (94). Some commentators have also warned of the dangers of underestimating the true numbers of birds killed depending on methodology applied (95). A number of mitigation measures have been proposed, and to some extent tested and implemented, in various parts of the species’ range, especially Australia, including setting nights by night (instead of by day), particularly during new moon period, using bird-scaring lines, using machines to cast baits clear of vessel wash during line setting, weighting lines more heavily so that they sink more quickly, thawing bait, using bait that sinks more readily, closing fishing areas or seasons, and not dumping offal near fishing lines during setting and hauling (96). As a result, within that part of the Southern Ocean managed by the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), which includes waters around South Georgia, Prince Edward Is, the Crozet and Kerguelen archipelagos, seabird bycatch has been reduced to negligible levels (in demographic terms) over the last decade (97); nevertheless, further reduction appears possible if mitigation methods can be optimized (98). Elsewhere, recent large-scale volcanic eruptions at Heard I (2003–2004 in particular) may have caused most birds to desert nesting sites, while explosion in European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) numbers on Macquarie I since 1999 has led to extensive destruction of habitat and soil erosion at nesting sites (an eradication programme targeting rodents commenced in 2010) and cats (Felis catus) are thought to impact colonies on Kerguelen Is at Jeanne d’Arc Peninsula. Predicted levels of climate change (increasing sea surface temperatures and decrease in sea ice extent) could have a markedly negative effect on this species, especially as its survival is already known to be affected by climatic fluctuations (99); however, at the local level, climate change can have positive effects, for example glacier retreat on Heard I has enabled the colony there to expand (100). Mercury contamination is potentially an issue in some parts of the species’ range, notably at South Georgia, although T. chrysostoma appears to be more affected (101). In addition, synthetic materials regularly appear in this albatross’ stomach contents, e.g. thermoplastic, nylon, rubber and metal wire, all of which could be extremely harmful (40).

Black-browed Albatross (Campbell)

VULNERABLE. Population most recently (1995–1997) estimated at 24,600 pairs on Campbell I (where also c. 30 pairs of T. melanophris) (2), where many more prior to 1970s (one colony declined at a rate of 5·9% per year between 1966 and 1981, and 10·5% per year between 1981 and 1984), but numbers increased at rate of 1·1–2·1% per year in 1992–1996 (79), following decrease in tuna (Thumnus sp.) longline fishery in this region (2). The trend over the past three generations (85 years) is currently assumed to be negative, but, based on the decrease in fishing effort following a peak in 1971–1983, the population is considered likely to continue to expand. Large numbers caught by tuna longline vessels, mostly juveniles in New Zealand waters, but also adults in Australian waters, and the population decline coincided with the development of a large-scale fishery, whereas the present gradual increase in numbers may be due to a substantial decline in fishing effort since 1984. However, during 1988–1995, it still comprised 11% of all the seabirds killed on tuna longlines in New Zealand waters and returned for identification, and 13% of all banded birds caught in Australian waters. It is also attracted to offal discarded from trawlers, and is regularly drowned in New Zealand trawl fisheries. The species was first studied in the 1940s. Feral sheep were eradicated from the north of Campbell I, where the nesting colonies are sited, in 1971, and then from the island itself in 1991. Current research includes studies on population dynamics, colony distribution, biology, diet and foraging. Furthermore, the islands form a national nature reserve, and part of a World Heritage Site, declared in 1998. Rats and cats were eradicated from Campbell in 2001, and an expedition in 2003 found no evidence of them persisting.