Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (59)

- Monotypic

Text last updated August 21, 2017

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Swartkopmeeu |

| Albanian | Pulëbardha e zakonshme |

| Arabic | نورس اسود الرأس |

| Armenian | Սովորական որոր |

| Asturian | Gaviota ridora |

| Azerbaijani | Göl qağayısı |

| Basque | Antxeta mokogorria |

| Bulgarian | Речна чайка |

| Catalan | gavina riallera |

| Chinese | 紅嘴鷗 |

| Chinese (Hong Kong SAR China) | 紅嘴鷗 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 红嘴鸥 |

| Croatian | riječni galeb |

| Czech | racek chechtavý |

| Danish | Hættemåge |

| Dutch | Kokmeeuw |

| English | Black-headed Gull |

| English (United States) | Black-headed Gull |

| Faroese | Fransamási |

| Finnish | naurulokki |

| French | Mouette rieuse |

| French (France) | Mouette rieuse |

| Galician | Gaivota chorona |

| German | Lachmöwe |

| Greek | Καστανοκέφαλος Γλάρος |

| Hebrew | שחף אגמים |

| Hungarian | Dankasirály |

| Icelandic | Hettumáfur |

| Indonesian | Camar kepala-hitam |

| Italian | Gabbiano comune |

| Japanese | ユリカモメ |

| Korean | 붉은부리갈매기 |

| Latvian | Lielais ķīris |

| Lithuanian | Rudagalvis kiras |

| Malayalam | ചെറിയ കടൽക്കാക്ക |

| Marathi | काळ्या डोक्याचा कुरव |

| Mongolian | Хүрэн толгойт цахлай |

| Norwegian | hettemåke |

| Persian | کاکایی سرسیاه کوچک |

| Polish | śmieszka |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | gaivota-de-capuz-escuro |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Guincho-comum |

| Romanian | Pescăruș râzător |

| Russian | Озёрная чайка |

| Serbian | Obični galeb |

| Slovak | čajka smejivá |

| Slovenian | Rečni galeb |

| Spanish | Gaviota Reidora |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Galleguito raro |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Gaviota Encapuchada |

| Spanish (Peru) | Black-headed Gull |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Gaviota Cabecinegra Europea |

| Spanish (Spain) | Gaviota reidora |

| Spanish (Uruguay) | Black-headed Gull |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Gaviota Risueña |

| Swedish | skrattmås |

| Thai | นกนางนวลขอบปีกขาว |

| Turkish | Karabaş Martı |

| Ukrainian | Мартин звичайний |

Chroicocephalus ridibundus (Linnaeus, 1766)

Definitions

- CHROICOCEPHALUS

- ridibunda / ridibundum / ridibundus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

37–43 cm; 195–325 g; wingspan 94–110 cm. Two-year gull. The breeding adult has the frontal hood dark chocolate brown to dusky blackish, with blackish border; whiteeye-crescents , mainly behind eye; neck white; underparts white, but in some populations (e.g. in Norway) up to 50% of arriving adults have pink bloom on underparts; back, upperwing-coverts, secondaries and inner primaries grey, secondaries with white tips; outerprimaries white, edged and tipped black; tail white; bill and legs dark red; eye dark brown. Distinguished from slightly larger but very similar Brown-headed Gull (Chroicocephalus brunnicephalus) by largely white leading edge to wing, lacking black wingtip with white subterminal spots. Differs from slightly smaller but almost identical Brown-hooded Gull (Chroicocephalus maculipennis) in having black tips to outermost primaries.Non-breeding adult has whitehead , but retains a dusky spot on ear-coverts and some blackish clouding on nape.

Juvenile has extensive rich buff to darker brown markings on upperparts and upperwing-coverts; black terminal band to tail; bare parts duller. First-winter birds combine an adult-type head and body with juvenile-type wings and tail; the dark-centred tertials are particularly distinctive on settled birds. First-summer birds develop a variable dark hood, duller than in adults, and retain the first-winter plumage, which becomes progressively bleached and worn. Second-winter birds resemble adult-winter but some show complete black webs to the outer 1 or 2 primaries and occasionally dark spots on the primary coverts, alula, tertials and tail (1).

Systematics History

Some recent authors place this species and other “masked gulls” in genus Chroicocephalus (see Bonaparte's Gull (Chroicocephalus philadelphia)). Sometimes treated as conspecific with Brown-headed Gull, the Pamir population showing characteristics intermediate between the two species. Hybridizes occasionally with Mediterranean Gull (Ichthyaetus melanocephalus) and reportedly with Common Gull (Larus canus) (1); has hybridized with Slender-billed Gull (Chroicocephalus genei) (2). NE Siberian population sometimes separated as a geographical race, sibiricus, slightly larger than those in rest of range, but differences minimal. Monotypic.

Subspecies

Hybridization

Hybrid Records and Media Contributed to eBird

-

Slender-billed x Black-headed Gull (hybrid) Chroicocephalus genei x ridibundus

-

Black-headed x Mediterranean Gull (hybrid) Chroicocephalus ridibundus x Ichthyaetus melanocephalus

-

Black-headed x Common Gull (hybrid) Chroicocephalus ridibundus x Larus canus

-

Black-headed x Ring-billed Gull (hybrid) Chroicocephalus ridibundus x Larus delawarensis

Distribution

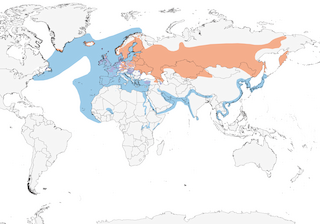

S Greenland and Iceland through most of Europe and C Asia to Kamchatka, extreme SE Russia (Ussuriland) and NE China (Heilongjiang); marginal in E North America (extreme SE Canada and adjacent NE USA). Winters S to W & E Africa, India, and SE Asia.

Habitat

Temperate zone to edge of boreal forests of Palearctic; mainly at low altitudes, and generally near calm, shallow water of coastal or inland waters, including rivers and their estuaries. Chiefly an inland breeder, with much breeding habitat created by rising water levels, and colonies eventually abandoned when water levels fall and leave dry basin; in many places, however, nests on relatively dry sites, e.g. moors, sand dunes and beaches. Overall, most colonies on freshwater lakes and marshes, but invading certain coastal areas (e.g. coasts of Baltic and North Seas) in huge numbers; in Scandinavia, has recently adapted to colonize salt-marshes, settling ponds, clay pits and coastal dunes and offshore islands. In very wet years may nest in low trees. Often found on sewage farms or near canals.

In winter, tends to occur far more in coastal habitats, but also inland at relatively low elevations. Commonly found in harbours and around sewage outfalls. Seldom far offshore, except on passage. Frequents pastures and farmland, including ricefields, flocks often following the plough. Very large numbers are attracted with other gulls to landfill rubbish dumps: in Iberia this habit has seen a major shift in recent decades towards wintering far inland around major cities instead of on coasts (3). Birds that winter inland roost on lakes and reservoirs, often in very large numbers.

Movement

Northern populations are migratory, while lower latitude birds tend to be resident or dispersive. Most birds breeding in Switzerland migrate to the W Mediterranean; Scandinavian breeders migrate to Britain and many follow Atlantic coast down to W Africa, but most birds wintering in Britain originate from the Baltic republics. Most of those wintering in Spain originate from France/Belgium, with the remainder largely from northern and eastern Europe: there are recoveries from Spain of birds ringed in almost every European country east to Western Russia, showing that some birds move westwards as well as southwards to winter (3). Winters commonly throughout the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins, and in the Caspian Sea.

Abundant in N Africa and the Middle East in winter, chiefly along coasts. Small numbers ascend the River Nile and it is a common visitor to the Red Sea, the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf; uncommon along Rift Valley and the E African coast, the winter range having extended to tropical East Africa fairly recently. In West Africa some hundreds at least winter regularly south to Mauritania, Senegal, Ghana and the Cape Verde Islands: there are reports of 3000–4000 in winter from Senegal (4). Some winter inland in W Africa along the Niger river in Mali and Niger, and in Nigeria and Chad; a few non-breeders oversummer in W Africa (5). Vagrants have been recorded widely throughout southern Africa, both inland and on coasts, south to the Cape (6).

Asian birds winter S to India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Philippines. It is a fairly common migrant and winter visitor to Nepal. Flocks of up to 12,000 occur in Hong Kong in winter, where wintering numbers increased from c. 100 in 1970 to 15,000–20,000 by the mid 1990s (1). It is abundant throughout Japan from Kyushu northwards in winter, both in coastal waters and inland (7). It has become increasingly common in N Borneo in winter, where it is the only gull recorded, especially around Sandokan and Kota Kinabalu (8). Wintering birds have also become regular in N Wallacea, October–April, particularly in Sulawesi and N Moluccas, and there are records from New Guinea (9, 10). Rare vagrants have reached N Australia (11).

Some Asian birds reach the W Aleutians and Pribilofs outside the breeding season and vagrants have been reported on the N. American Pacific coast from south coastal Alaska south to California. In the East it remains fairly common in Newfoundland, the principal breeding area, in winter, when it also occurs less commonly along the St Lawrence seaway and south along the East coast to New Jersey, with vagrants recorded south to Florida and the Gulf Coast states and throughout the Caribbean and south to Trinidad and Tobago (12, 13). There are also records from French Guyana and Colombia (14). The wintering birds in NE America, several thousand birds, include a proportion from Iceland and Greenland (1).

Diet and Foraging

The reported diet is extremely broad and opportunistic but shows a tendency towards a greater reliance on natural foods during the breeding season and on foods of anthropogenic origins in winter (15). The breeding season diet varies according to location but often includes large quantities of aquatic and terrestrial insects as well as earthworms. In Baltic, 93% of stomachs contained insects, 5% molluscs, and 3% each oligochaetes (May only) and fish. Flocks may 'flycatch' flying insects, such as ants or chironomids, when these are abundant (16). Birds nesting at coastal colonies may also rely on marine invertebrates , and to lesser extent on fish. Habitat switching between inshore, intertidal and terrestrial habitats is reported from coastal colonies on the German coast and may be widespread; switching may occur on a daily basis (related to tidal cycle) and over the whole breeding season, the latter switch most probably being the result of lower prey availability in the terrestrial habitats and an increasing quality (in terms of prey abundance and energy intake) of the marine area (17).

Feeds by swimming and seizing objects from surface, or dipping head under surface; along coast, by walking on mudflats and probing for shrimps and marine worms; sometimes by foot-stirring and foot-paddling. Also follows fishing boats and ferries that churn up food items, and may feed at night. Plant material is taken opportunistically: it includes fruits and seeds from trees and shrubs in summer in autumn; for example, olives, figs and acorns, and cereal grain from autumn stubble or spring sowings (15). Frequently kleptoparasitic in Europe on Northern Lapwing (Vanellus vanellus) and European Golden-Plover (Pluvialis apricaria) feeding on pastures, where it steals earthworms; also robs Northern Lapwings and other waders on mudflats; kleptoparasitism has been shown to be most effective when practiced by adults, suggesting that it is a skill that is refined over time (18, 19). Occasionally kleptoparasitic on terns and and takes eggs but not chicks of Sandwich Tern (Thalasseus sandvicensis)). In non-breeding season, also relies heavily on various artificial food sources provided by man , especially in W Europe; following fishing boats near harbours, frequenting sewage outfalls, taking scraps in parks and feeding at landfill rubbish dumps. Different individuals have been shown by experiment to develop preferences for either anthropogenic or natural foods in winter, perhaps as a result of early experience (20).

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Notoriously noisy at breeding colonies, producing screaming, downslurred but melodious "krreeaarh" or similar calls, often repeatedly. Feeding flocks often give similar but quieter calls. Also gives a short "kek" or "kekekek" (21).

Breeding

Returns to colonies from late February to late March; lays in late April and May. Most colonies 11–100 pairs, a few exceeding 10,000 pairs; inter-nest distances often average 1 m, and large, bulky nests often touch; solitary nesting generally rare, except in Sweden. Shows strong preference for nesting near vegetation, but some colonies deserted because of vegetation overgrowth; very variable substrate, including sand, vegetation, rocks and marshes. 1–3 eggs (mean 2·6–2·78); incubation 22–26 days; chick warm buff, boldly spotted with irregular black blotches on back and wings and smaller, rounder, sparser black spots on head; mean hatching weight declines from 26 g to 23 g during season; adults and chicks recognize each other by 4th day; fledging by 35 days. Young birds likely to return to breed in natal colony; few breed at 2 years. Recorded longevity of at least 33 years (22).

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). The global population is estimated at around 4.8–8.9 million individuals. They mainly comprise 3.7–4. million individuals in W Europe together with the W Mediterranean, 770,000–1.8 million birds in E Europe including the Black Sea and E Mediterranean, and 250,000 in W and SW Asia and NE Africa (23). Within Europe, national populations approaching or exceeding 100,000 pairs are recently reported from Belarus, the Czech Republic, Finland, Germany, The Netherlands, Poland, Sweden and the United Kingdom, and there may be 200,000–500,000 pairs in Russia.

In the early 1980s the world population was around 2.0 million pairs, following a rapid geographical spread and population increases during 1950–1980, but later increases have been slower and an overall declining trend is now reported, although with clear regional variation Birdlife Datazone . Local factors may be responsible for some observed population changes; for example, at one site in Netherlands, eggs were collected until 1963 in order to protect colonies of Sandwich Terns Thalasseus sandvicensis; when collecting ceased, the population rebounded, increasing from 170 pairs to 6000 pairs in ten years. Similarly, at least formerly, congenital defects attributed in part to chemical pollutants were numerous in Czech and Slovak colonies, affecting 3–5% of eggs, and were particularly common in single-egg clutches.

Westward range expansion across the N Atlantic began early in the 20th century. Iceland and Greenland were colonised in about 1910 and 1969 respectively; the respective populations are recently estimated at 25,000–30,000 pairs and 5–50 pairs respectively (24). In N America records became increasingly frequent from the 1950s onwards and the species first bred in 1977, in E Canada; there are now several small breeding colonies in Canada, west to Quebec but chiefly in Newfoundland, and in New England (12).

Southward range expansion in the W Mediterranean is relatively recent. The first known instance of breeding in the Iberian Peninsula was in 1960 at the Ebro delta; breeding in Spain became increasingly widespread by the late 1970s and there were over 9,000 pairs censused in 2007, at 40 sites, including the Ebro delta which held over 4,000 pairs (25, 3). Breeding in Portugal was first reported in 1995 at the Sado estuary but remains minimal (3). The species has been recorded breeding in Morocco since 2002 (26, 27), in Algeria since 2006 (28) and most recently in Tunisia (29).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding