Parkinson's Petrel Procellaria parkinsoni Scientific name definitions

- VU Vulnerable

- Names (27)

- Monotypic

Text last updated June 10, 2014

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Catalan | baldriga de Parkinson |

| Czech | buřňák černý |

| Dutch | Zwarte Stormvogel |

| English | Parkinson's Petrel |

| English (Australia) | Black Petrel |

| English (New Zealand) | Parkinson's Petrel (Black Petrel) |

| English (United States) | Parkinson's Petrel |

| French | Puffin de Parkinson |

| French (France) | Puffin de Parkinson |

| German | Schwarzsturmvogel |

| Icelandic | Munkadrúði |

| Japanese | クロミズナギドリ |

| Norwegian | fjellpetrell |

| Polish | burzyk czarny |

| Russian | Чёрный буревестник |

| Slovak | víchrovník čierny |

| Spanish | Pardela de Parkinson |

| Spanish (Chile) | Petrel de Parkinson |

| Spanish (Costa Rica) | Petrel de Parkinson |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Petrel de Parkinson |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Petrel de Parkinson |

| Spanish (Panama) | Petrel de Parkinson |

| Spanish (Peru) | Petrel de Parkinson |

| Spanish (Spain) | Pardela de Parkinson |

| Swedish | mindre sotpetrell |

| Turkish | Kara Yelkovan |

| Ukrainian | Буревісник чорний |

Procellaria parkinsoni Gray, 1862

Definitions

- PROCELLARIA

- parkinsoni

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

Parkinson's Petrel is the smallest member of the black petrel group in the genus Procellaria; while species within this complex are difficult to identify, they are typically separable in life given good views or photos. About the size of Pink-footed Shearwater, Parkinson's Petrel is all dark brown or black with a small, rounded head and long primary projection, and has a dark tip to an otherwise horn-colored, distinctly plated bill. The species nests only on Great and Little Barrier Islands of New Zealand, but disperses throughout the south Pacific Ocean as far east as the waters of the Humboldt Current offshore of western South America. Longline fishing as well as the introduction of cats and rats to the breeding islands have proved to be major threats to the small population of Parkinson's Petrels, but conservation measures underway in New Zealand appear to be helping the species.

Field Identification

41–46 cm (1); 585–989 g (2, 3); wingspan 112–123 cm (1). Entirely sooty black , often darkest on head and neck; underside of primary bases and coverts slightly paler and greyer; iris blackish brown; bill ivory-yellow, culmen and tip variably tinged grey; legs blackish. Sexes alike, but male marginally larger in wing and bill measurements (2). Juvenile as adult, but in fresh plumage in May–Aug, when older birds are heavily worn or in moult (1); body- and flight-feathers unmoulted during first year, and bill tends to have reduced yellowish tones, sometimes tinged greyish, bluish or pink (4). Smaller and less bulky than P. aequinoctialis; hardly separable from very similar <em>P. westlandica</em> , though has slightly smaller bill and is smaller overall and narrower-winged, bill usually paler on tip and culmen, so can be more visible at sea, making size comparison more difficult, perhaps slightly slimmer-bodied, the neck being marginally more noticeable, especially when head held slightly higher than body (differences clearer compared to P. aequinoctialis), feet project more obviously beyond tail tip (4), and perhaps tends to have slightly more contrastingly grey bases to primaries on underwing compared to P. westlandica. Being smallest of genus, could be confused with largest all-dark Ardenna, dark morph of Ardenna pacificus slimmer, long-tailed and has thin bill, while much more similar <em>A. carneipes</em> has slightly slimmer and longer-looking bill , and leg colour can also help.

Systematics History

Subspecies

Distribution

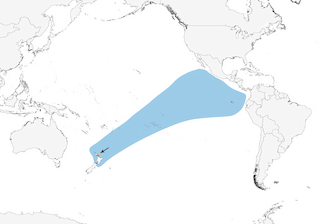

Tropical C & E Pacific Ocean, breeding on Little Barrier I and Great Barrier I, off NE North I (New Zealand).

Habitat

Marine and pelagic; usually occurs far from coast, avoiding inshore waters, except around colonies. Breeds on forested ridges in highlands.

Movement

Migratory; most birds move E over C Pacific to W coasts of Central and South America, mainly between SW Mexico at 15º N (off Guerrero) (1) and N Peru (12º S) (5), as well as W along equator to 110º W (2), with an exceptional record off C California (Oct 2005) and an unverified report from Oregon (also Oct 2005) (1); considered to be most common off coasts of Ecuador and Peru. Recorded in N Chile (Dec 2010) (6). Species is present off Middle America year-round, but mainly Mar/Apr–Oct (1), with records off South America (Colombia) as early as mid Feb (7) Small numbers occur off E Australia, where claimed off New South Wales in Feb and Nov (8), although only two accepted records (most recently Oct 2010) (9), and also recorded S to Ross Sea, E Antarctica (4). During breeding season mainly occurs in subtropical waters around North I, New Zealand, between c. 30º S and 42º S, and 150º E and 175º W (2), but is known to range up to 1130 km from colonies though generally does not reach > 550 km away from the species’ breeding sites (3).

Diet and Foraging

Mostly cephalopods (Ommastrephes bartrami, Histioteuthis), at least during breeding season (2), with some fish and small proportions of crustaceans. Captures prey by surface-seizing ; also surface-dives and pursuit-plunges that can last up to 20 seconds (2). Feeds mainly by night, either alone or in loose monospecific flocks of up to 300 birds (10), sometimes within mixed-species flocks of other seabirds (4). Often scavenges around trawlers and readily approaches boats in general (11). Regularly associates with cetaceans, especially during non-breeding season, e.g. false killer (Pseudorca crassidens) and melon-headed whales (Peponocephala electra); during surveys in E tropical Pacific between 1976 and 1990, of 618 individual petrels observed, 469 (76%) were associated with ten different species of dolphins, on 55 occasions (10, 2).

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Vocalizes only at colonies and after dark, with three main calls identified: a Clack is the commonest, which is a series of far-carrying, staccato pulses given from birds on ground or in burrow; high-pitched Throaty Squawks that are given during disputes; and Aerial Calls, which are only rarely heard (2). Considered to be probably silent at sea (4).

Breeding

Starts Nov, with colony return from c. 10 Oct, followed by pre-laying exodus of c. 23 days (both sexes), egg-laying mostly 20 Nov and 25 Dec (and up to ten days either side of this), and young fledging mid Apr to late Jul (2). Exclusively nocturnal at breeding sites (2); long-term monogamous and territorial around burrow entrances (4). Up to 22·4% of adults may skip breeding during any given season (2); burrow use on Great Barrier I between the 1995/96 and 2004/05 seasons by breeding birds was 60–70%, by non-breeding birds 20–25% and the remaining burrows were empty (12). Colonial; nests in self-excavated burrows 1–3 m long (2), cavities, hollow logs and amongst tree roots, with sparse nest lining (4). Single white egg, mean size 69·3 mm × 50·5 mm (2); incubation 56·5 days (single record), with stints of c. 8–17 days (2); chicks have black down , probably brooded for less than one day, thereafter fed on c. 50% of nights during first ten days of life and c. 35% of nights at age one month, with meal size ranging from 89 g to 167 g (mean 121 g) (2); fledging 96–122 days at 725–794 g, but achieves peak weight in excess of 1000 g earlier than this (2). Hatching success c. 84%, fledging success very low on Little Barrier I prior to cat eradication (2), while overall breeding success on Great Barrier I between 1996 and 2000 ranged from 75% to 97% (13). Sexual maturity at c. 6–8·5 years, although birds can return to colony after five years (14, 2). During 1986–1990, a maximum of 42% fledglings survived to six years old; the 1990 cohort had significantly better survival than 1986–1989 cohorts, and this cohort, just 21% of experimental birds (transferred to Little Barrier I), contributed 43% of chicks known to have been reared by experimental birds prior to 2001, with neither body mass at departure nor El Niño-Southern Oscillation clearly related to differential survival, but given that fledglings were always transferred at similar developmental stages, the earliest transfer of heavy fledglings was most successful (14). Adult survival estimated at 88% (2). Known to have lived at least 17 years.

Conservation Status

VULNERABLE. Total population variously estimated at c. 2600 breeding pairs and c. 10,000 individuals (2), or 1400 breeding pairs and c. 5000 individuals, although at-sea surveys between 1980 to 1995, involving 1020 hours covering 14,277 km² of ocean off Chile to Panama, estimated as many as 38,000 individuals during the austral autumn (28,000–50,000) (15). Slowly recovering after eradication of cats from Little Barrier I in 1980 and perhaps boosted by transfer of 249 chicks from nearby Great Barrier I between 1986 and 1990 (14, 2); heavy predation for over a century; cats (introduced in 1800s) (2) killed 65% of all fledglings in 1972, 90% in 1973, and 100% in 1974 and 1975, as well as many adults; colony was in process of rapid decline, but saved when only a few hundred birds remained. Larger colony on Great Barrier I suffers comparatively little predation by cats and rats (though latter varied from 1·4% and 8% between 1996 and 2000) (13), perhaps because presence of Pterodroma cookii absorbs predation pressure (2); a few may still be taken for food by Maoris. Formerly more widespread in New Zealand, breeding abundantly at several inland sites (above 300 m) (2) on North I and N regions of South I (2), where subjected to human exploitation; last bred on North I in 1958, at Taranaki (16, 2). Species saved from immediate extinction, but requires more suitable nesting habitat on other predator-free islands, to be able to build up adequate numbers; Great Barrier I seems suitable and efforts already being directed towards removal of cats. Some casualties amongst fledglings, when attracted to lights during first flight. Incidental mortality due to commercial fisheries, both during breeding and non-breeding seasons (12), may represent significant threat (17).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding