Eurasian Wigeon Mareca penelope Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (58)

- Monotypic

Text last updated August 26, 2016

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Albanian | Kryekuqe e madhe |

| Arabic | صواي أوراسي |

| Armenian | Շչան բադ |

| Assamese | খেৰী হাঁহ |

| Asturian | Corñu xiblador europñu |

| Azerbaijani | Fiyu ördəyi |

| Basque | Ahate txistularia |

| Bulgarian | Фиш |

| Catalan | ànec xiulador eurasiàtic |

| Chinese | 赤頸鴨 |

| Chinese (Hong Kong SAR China) | 赤頸鴨 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 赤颈鸭 |

| Croatian | zviždara |

| Czech | hvízdák eurasijský |

| Danish | Pibeand |

| Dutch | Smient |

| English | Eurasian Wigeon |

| English (United States) | Eurasian Wigeon |

| Faroese | Ennigul ont |

| Finnish | haapana |

| French | Canard siffleur |

| French (France) | Canard siffleur |

| Galician | Pato asubiador común |

| German | Pfeifente |

| Greek | (Ευρωπαϊκό) Σφυριχτάρι |

| Haitian Creole (Haiti) | Faldam etranje |

| Hebrew | ברווז צהוב-מצח |

| Hungarian | Fütyülő réce |

| Icelandic | Rauðhöfðaönd |

| Indonesian | Itik bungalan |

| Italian | Fischione |

| Japanese | ヒドリガモ |

| Korean | 홍머리오리 |

| Latvian | Baltvēderis |

| Lithuanian | Eurazinė cyplė |

| Malayalam | ചന്ദനക്കുറി എരണ്ട |

| Marathi | तरंग बदक |

| Mongolian | Зээрд алаг нугас |

| Norwegian | brunnakke |

| Persian | گیلار |

| Polish | świstun |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Piadeira |

| Romanian | Rață fluierătoare |

| Russian | Свиязь |

| Serbian | Zviždara |

| Slovak | kačica hvizdárka |

| Slovenian | Žvižgavka |

| Spanish | Silbón Europeo |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Pato euroasiático |

| Spanish (Dominican Republic) | Silbón Euroasiátic |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Pato Silbón |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Silbón Europeo |

| Spanish (Spain) | Silbón europeo |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Pato Silbón |

| Swedish | bläsand |

| Thai | เป็ดปากสั้น |

| Turkish | Fiyu |

| Ukrainian | Свищ євразійський |

Mareca penelope (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- MARECA

- mareca

- PENELOPE

- penelope

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

A buffy, medium-sized duck, the Eurasian Wigeon is an uncommon, but increasing vagrant to the new world. This species is listed in the neotropics as a rare winter visitor, with only a handful of reported sightings from northern Mexico (Howell and Webb 1995). When found in the Americas, Eurasian Wigeon are often seen associating with flocks of American Wigeon or other dabbling ducks in freshwater ponds or coastal marine environments. American and Eurasian Wigeons hybridize regularly, and hybrid individuals may occur in Mexico and Baja California. Sometimes placed in the genus Mareca, the Eurasian Wigeon forms a superspecies with the American and Chiloe Wigeons.

Field Identification

45–51 cm; male mostly 600–1000 g, female 500–800 g (1); wingspan 75–86 cm (1). Male has chestnut head and neck , with yellowish crown , sometimes has metallic dark green spot behind eyes and on throat, pinkish-grey breast , grey-vermiculated upperparts and sides, white lower breast and belly, contrasting with black surround to white-grey tail, white upperwing-coverts, elongated grey scapulars , dark green speculum edged black, grey-brown primaries and dusky grey axillaries (but note that both sexes can be much paler over both this tract and underwing-coverts ) (2); blue-grey bill with black tip, slate-grey legs and feet, and brown eyes; has female-like eclipse plumage , which is rich reddish chestnut, with darker upperparts than adult female, rufous flanks and contrasting white forewing. Female slightly smaller with dark head not contrasting with breast and upperparts, brown mantle , scapulars, upper breast and flanks barred pink-buff, with rest of underparts white marked darker on undertail-coverts, axillaries greyish, underwing fawn with paler markings, wing-coverts grey-brown, speculum blackish, and bill and legs duller grey-blue than in male. Juvenile similar to female, with mottled belly, while first-winter male is much like adult, although male does not acquire white forewing until second-winter, and first-winter female has less obvious whitish tips to wing-coverts than adult female.

Systematics History

Subspecies

Hybridization

Hybrid Records and Media Contributed to eBird

-

Gadwall x Eurasian Wigeon (hybrid) Mareca strepera x penelope

-

Eurasian x American Wigeon (hybrid) Mareca penelope x americana

-

Eurasian x Chiloe Wigeon (hybrid) Mareca penelope x sibilatrix

-

Eurasian Wigeon x Mallard (hybrid) Mareca penelope x Anas platyrhynchos

-

Eurasian Wigeon x Northern Pintail (hybrid) Mareca penelope x Anas acuta

-

Eurasian Wigeon x Green-winged Teal (hybrid) Mareca penelope x Anas crecca

Distribution

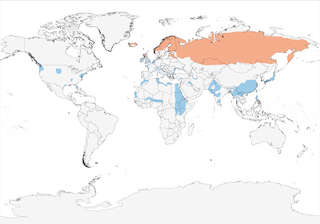

From Iceland and N Britain E across N Europe and N Asia to Pacific coast. In winter moves to C & S Europe, S Asia and N & C Africa, and reaches North America.

Habitat

Shallow, freshwater marshes, lakes and lagoons surrounded by scattered trees or open forest during breeding season, but in winter moves to coastal marshes, freshwater and brackish lagoons, estuaries, bays and other sheltered marine localities (5). In survey in S Finland, occurrence of females with broods was related to emerging flies (Diptera) and habitat structure, but associations were not strong (6). In Europe winters mainly in coastal marshes , freshwater and brackish lagoons, estuaries, bays and other sheltered marine habitats, but also recorded at inland dams and lakes, including to at least 3650 m in Ethiopia (7) and 2700 m in Kenya (8).

Movement

Basically migratory, descending to lower latitudes to winter throughout most of W & C Europe, Mediterranean Basin, Middle East, N & NE Africa (S to Tanzania), Indian Subcontinent (mainly in N, where only recorded in Bhutan as recently as 1986 (9), but S to Sri Lanka) (10), mainland SE Asia (where generally uncommon) and N Borneo (11), Taiwan and Japan , more exceptionally the Mariana Is (12), Palau, Yap, Chuuk, Marshall Is (13) and New Guinea. Some populations (e.g. British) mostly sedentary, although even these usually make short-range movements further SW (1). Winter range strongly dictated by the influence of climatic variables on foraging ecology, thus “cold-weather movements” are not result of falling temperatures alone (14). Post-breeding initially moves to moulting grounds, where breeders join immature non-breeders, and large gatherings have been noted in Estonia, S Sweden, Denmark and Netherlands (1). In Finland, return migration in autumn appears to have been getting later based on study of passage dates over 30-year period since 1979, perhaps as a result of climate change (15). Breeding populations in Fennoscandia and N Russia E to Yenisey migrate to W & SW Europe, whereas those breeding in W & C Siberia winter on Caspian and Black Seas W to Mediterranean, even as far W as Tunisia (1). In Old World, non-breeders have reached as far afield as Azores (at least 23 records), Madeira (very rare) Canaries (fairly regular visitor) and Cape Verdes (Dec 2004–Jan 2005) (16), as well as on Spitsbergen and Bear I (1), in W Africa scarce from Mauritania and N Senegal to Chad, with vagrants recorded in Gambia (17), Ivory Coast (18), N Ghana (19), SW Nigeria and N Cameroon (20), as well as Uganda (21) and Somalia (22). Typically present on wintering grounds between Sept/Oct and mid Mar to early Apr in NW Europe, with departure typically occurring earlier during mild winters (1); mainly Nov–Feb in Ethiopia, although even here regularly recorded 24 Oct–24 Apr, with several records in May–Jul (7, 23) and Dec to early Mar in Kenya (extreme dates mid Nov to mid Apr) (8); at Bharatpur, in N India, arrives late Sept and departs between early Apr and mid May (24). Occurs regularly on Atlantic and Pacific coasts of North America, as well as on Bermuda, with occasional records even further S, to Mexico (rare in S Baja California, Sonora and Tamaulipas, vagrant to Jalisco and Clipperton Atoll) and the West Indies (Bahamas, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Barbuda and Barbados), and even once in Venezuela (Mar 2002) (25). Barbudan record involved a bird ringed on Iceland (26).

Diet and Foraging

Essentially vegetarian ; leaves, stems, roots, rhizomes and seeds of grasses, sedges and aquatic vegetation, e.g. saltmarsh grass (Puccinellia maritima) (27), Salicornia ramosissima (28) and Zostera spp. (29) in winter; occasionally takes small invertebrates, especially ducklings, which are strongly dependent on chironomids in early days of life, but quickly switch to vegetable diet (5)., while adults may also feed extensively on such prey during breeding season (30) and has possibly been observed taking mayflies (Ephemeroptera) and caddis-flies (Trichoptera) in pre-breeding season (31), and potatoes in winter (32). Regularly uses rice fields in Japan and Korea in winter (33). During cold winter weather, also seen to feed on gull droppings (34). Feeds by grazing on dry land in tight packs (more so than Anas) (5), dabbling on water surface and head dipping in shallow water; appears to favour nitrogen-fertilized grasslands in early breeding season (35). In winter feeds both at day or night, according to tides (5). Repeated feeding on same areas is deliberate strategy to improve their dietary quality in late winter/early spring: M. penelope selectively graze small patches, resulting in a 52% increase in leaf production over the winter and, by the end of winter, 4·75% higher protein levels compared to plants that were ungrazed (36). Regularly consorts with other wildfowl in winter, such as Branta leucopsis (27), Anas fabalis (37) and Branta bernicla (29). Given that Branta bernicla is also heavily dependent on Zostera beds for grazing in some areas, spatial segregation between geese and ducks was studied in SW England, where it appears that B. bernicla extracts rhizomes and consumes whole plants, whereas M. penelope take floating above-ground parts of Zostera; nevertheless, despite the spatial separation, some exploitative competition must occur via the removal by geese of potential feeding resources for the ducks (38).

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Most characteristic is piercing, whistled “whee-OOO” by male, given both in flight, on water or while foraging, but also utters multisyllabic “wip ... wee ... wip-weu” calls in threat; female gives low purring or growled “krr”, most frequently uttered when flushed and which lacks quacking quality of many other Mareca and Anas (5).

Breeding

Starts Apr–Jun, varying across range according to latitude, with nests sometimes initiated in Apr in Scotland, but may not arrive on breeding grounds in N Russia until second half of May (5); mean date of first laying 19–30 May in Iceland (1). Arrives on breeding grounds in small groups of 25–30 individuals (5). Monogamous, with pair-bonds maintained until soon after clutch is initiated, but may then be re-established in winter (39, 5, 40). Sometimes double-brooded and, more commonly, will re-lay if first clutch is lost (5). In single pairs or small groups (which may nest within 5 m of one another) (1), with extent of territoriality varying and females are frequently faithful to natal area (5); nest is depression on ground, lined with grass, sometimes twigs (5), and a thick coat of down, hidden among vegetation and usually close to water, but can be up to 250 m distant (1). Usually 8–9 cream- or buff-coloured eggs (6–12), size 49–60 mm × 35–42 mm, mass (in captivity) 32–47·5 g (5); incubation 24–25 days by female alone (5); chicks have dark or sepia-brown down above, paler below, with grey bill, olive-brown legs and feet, and brown eyes, and weighs mean 25·8 g at one day old (in captivity) (5); fledging c. 40–45 days, with female remaining with brood in nursery area virtually throughout this period (5). Breeding success variable: of 301 eggs laid in Finland, 78% hatched and 34% of young fledged (5), but in another Finnish study breeding success averaged 63% (41), whereas hatching success at 551 nests in Iceland in 1961–1970 averaged 68% (range 40–81%), and at 148 Scottish nests 55% hatched, 44% were predated and 1% were deserted; principal causes of failure at Icelandic nests were predation by Common Ravens (Corvus corax) and American mink (Mustela vison), followed by desertion (5). Other potential predators of eggs and young include Hooded Crows (Corvus cornix) red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) (42). A more recent Icelandic study, centred on L Myvatn, found that mean brood size was 3·93 and a mean 2·83 young fledged per female (range 0·09–5·14), with breeding success positively related to chironomid abundance and negatively to cold and wet weather (43), while in S Finland number of fledglings per breeding attempt was 0·11–2·2 (44). Sexual maturity at one, occasionally two, years. Predators of adults include Gyrfalcons (Falco rusticolus) (45) and Western Marsh-harriers (Circus aeruginosus) (46). Annual adult survival is c. 64%, with sex ratio of adult population skewed towards adults, whereas among young it is equal, while proportion of young in winter flocks varies, as expected, from 21–46% (5). Study of hunting returns found that proportion of juveniles decreased from 80% (females) and 74% (males) in Finland to 63% and 45% in Denmark, respectively, and estimated autumn juvenile survival as 29% for females and 22 % for males, i.e. far lower than in adults, consistent with findings for Anas crecca, and perhaps reflecting a wider pattern in dabbling ducks (47). Longevity record is 33 years and seven months (5).

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). Abundant, concentrates in large numbers in wintering grounds, at which season five main populations identified, namely in NW Europe (which held 1,500,000 in 1990s, of which c. 400,000 were in British Isles, with 50,000 on Somerset Levels alone in winter 2010/11) (48, 49), Black Sea/Mediterranean (300,000), SW Asia/NE Africa (250,000), S Asia (250,000) and E Asia (500,000–1,000,000, of which most in China, with considerably smaller but increasing numbers in Korea and Japan) (5, 50, 51). In Europe largest numbers breed in Sweden (20,000–30,000 pairs in late 1980s, stable, and has started to winter in S of country in recent decades) (52) and Finland (60,000–80,000 pairs, probably increasing), with 170,000–230,000 pairs estimated in European Russia (1); numbers breeding in other European countries typically < 5000 pairs, e.g. usually < 150 pairs in British Isles (53), but is expanding in range, having recently colonized Czech Republic (54). Winter 1991 census yielded 34,403 birds in Iran, 61,900 in Azerbaijan, 39,984 in Japan (quite a lot more individuals counted than in other years), and in partial counts in same year 23,355 individuals reported in India, 131,725 in Pakistan and 7946 in China. Overall numbers perhaps quite stable in recent years despite intense human pressure from hunting (c. 60,000 taken legally in UK each winter) (5), recreational activities (5) and drainage of habitat, partially compensated by establishment of reserves in many wetlands in W Europe, with most wintering sites in NW Europe and Mediterranean region now under some form of protection (5); nevertheless, individual wintering populations have been subject to significant fluctuations, with that in NW Europe showing significant upsurge over past three decades, apparently increasing at rate of 7·5%/year, whereas Black Sea/Mediterranean population has shown rapid decline over same period, perhaps in line with decreases reported on Russian breeding grounds, with numbers in W Mediterranean having fallen by 45% and those further E by perhaps 50% since 1982 (5), e.g. in Turkey, regularly in excess of 150,000 during 1960s and 1970s (exceptionally c. 459,000 in 1968/69), but just four counts > 40,000 between 1986 and 2005 (55). An analysis of mid-January counts in W Europe during 1990–2009 shows increases in abundance in the N and E of the wintering range (Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Switzerland), stable numbers in the central range (Belgium, Netherlands, UK and France) and declining abundance in the W and S of the wintering range (Spain and Ireland) suggesting a shift in wintering distribution consistent with milder winters throughout the range (56). Winter numbers in SW Asia have also probably fallen, by up to 62% in Iran, but perhaps less elsewhere (5). In UK, although upward trend in numbers wintering has been recorded in recent decades, there has been a significant decline in proportion of young there and some evidence that selective hunting affects age (but not sex) ratios in winter (57). Trends further E in Asia are poorly known. CITES III in Ghana.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding