Black-capped Petrel Pterodroma hasitata Scientific name definitions

- EN Endangered

- Names (36)

- Monotypic

Revision Notes

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Catalan | petrell del Carib |

| Czech | buřňák černotemenný |

| Danish | Cariberpetrel |

| Dutch | Zwartkapstormvogel |

| English | Black-capped Petrel |

| English (United States) | Black-capped Petrel |

| French | Pétrel diablotin |

| French (France) | Pétrel diablotin |

| Galician | Freira das Antillas |

| German | Teufelssturmvogel |

| Greek | Μαυροκέφαλος Πτεροδρόμος |

| Haitian Creole (Haiti) | Chanwan Lasèl |

| Hebrew | סערון שחור-כיפה |

| Hungarian | Karib viharmadár |

| Icelandic | Blesudrúði |

| Japanese | ズグロシロハラミズナギドリ |

| Lithuanian | Karibinis audrašauklis |

| Norwegian | vestindiapetrell |

| Polish | petrel antylski |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | diablotim |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Freira-das-antilhas |

| Romanian | Petrel caraibian |

| Russian | Черношапочный тайфунник |

| Serbian | Crnokapa burnica |

| Slovak | tajfúnnik čiapočkatý |

| Slovenian | Karibski švigavec |

| Spanish | Petrel Antillano |

| Spanish (Costa Rica) | Petrel Gorrinegro |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Pájaro de La Bruja |

| Spanish (Dominican Republic) | Diablotín |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Petrel Antillano |

| Spanish (Spain) | Petrel antillano |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Petrel Cabecinegro |

| Swedish | karibpetrell |

| Turkish | Kara Başlıklı Fırtınakuşu |

| Ukrainian | Тайфунник кубинський |

Revision Notes

The Conservation and Management page was updated to reflect the species' listing on the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

Pterodroma hasitata (Kuhl, 1820)

Definitions

- PTERODROMA

- hasitata

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

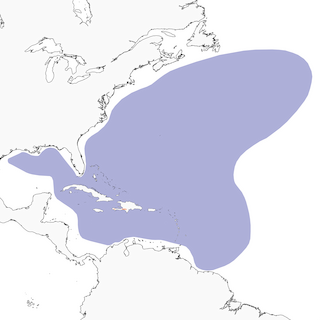

The Black-capped Petrel, known as Diablotin ("the little devil") in the Caribbean countries where it nests, is a large gadfly petrel present in the western North Atlantic and adjacent basins of the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico. It is considered Endangered, and its population is estimated at ~1,000 breeding pairs. On a foggy night in the mountains of Hispaniola, you may hear its eerie calls coming from underneath the forest bed; on a windy day off North Carolina, you may encounter it arcing above the waves with a few of its conspecifics. Like most other petrels in the North Atlantic, the recent history of Black-capped Petrel is one of ebullience and disappearance, of quasi-extinction and resilience. But like no other, this enigmatic seabird links worlds and people that never meet, from the cloud forests of the Caribbean’s highest mountains to crystalline waters of the Gulf Stream, from Haitian farmers to Carolinian offshore fishermen.

The only gadfly petrel currently known to breed in the Caribbean (the Jamaican Petrel, a distinctive taxon which some authorities consider a separate species, is likely extinct), the Black-capped Petrel used to be widespread in the Caribbean Basin and nested on at least six of its main islands (from west to east: Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola, Guadeloupe, Dominica, and Martinique). The species was reported as common up to the 1800s, but it suffered a precipitous decline due to intensive and sustained harvest by European colonists since the 1600s, and the accidental or deliberate introduction of mammalian predators on all of its breeding grounds. By the 1920s, the species was considered on the verge of extinction, if not extinct. Although likely known by local people, the locations of its breeding areas were lost to science until 1963, when David Wingate rediscovered breeding colonies (but did not confirm nesting activity) in the Massif de la Selle in Haiti after hearing vocalizing Black-capped Petrels. Other populations of calling petrels were identified in Haiti and the Dominican Republic in the 1980s, but it was not until 2002 that the first active nest was located by Theodore Simons and team. From 2008 to 2011, listening surveys by James Goetz and colleagues confirmed the presence of the Black-capped Petrel in the Haitian mountain ranges of Massif de la Hotte and Massif de la Selle. Finally, in 2011, almost fifty years after Wingate’s rediscovery, Ernst Rupp and Grupo Jaragua discovered the first active nest with a chick near the border between Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Since then, nesting activity has only been confirmed on Hispaniola but is highly suspected to occur in Dominica and Cuba, and probable in Guadeloupe and Jamaica.

At sea, the Black-capped Petrel was recorded throughout the Caribbean up to the 1800s. In the 1980–1990s, repeated surveys off the coast of the southeastern United States regularly recorded petrels in Gulf Stream waters from North Carolina to Florida. In the 2000s, additional systematic and opportunistic at-sea surveys recorded high numbers of Black-capped Petrels in this area, identifying it as the main marine range for the species year-round. Tracking studies in the 2010s confirmed the use of Gulf Stream waters but also highlighted the significant use of the southern Caribbean Sea by breeding adults. In parallel, recent at-sea surveys in the northern Gulf of Mexico recorded a regular presence in that region.

The small and declining population is affected by threats on land (including, but not limited to, deforestation for agriculture, predation by introduced mammals, light attraction, and collision with communication towers) and at sea (mostly mercury, plastics, and other contaminants, oil spills and attraction to oil platforms, and the effects of climate change such as the reduction of prey availability and increased hurricane frequency). In 2008, the International Black-capped Petrel Conservation Group was created to tackle these threats by promoting unified and coherent conservation actions. The first version of the Conservation Action Plan for the Black-capped Petrel (1) was produced following a 2010 workshop, and the group has been active in its implementation and adaptation ever since. A Conservation Update and Action Plan for the Black-capped Petrel was published in 2021 (2).

Adding to an already complex natural history and conservation situation, two distinct forms of Black-capped Petrels exist within the nominate subspecies, varying in the amount of white/dark plumage. The causes of these differences are still not well understood and are the subject of much speculation and questioning, including whether these differences warrant new subspecies (or even species) taxonomy. The little devil lives up to its name by complicating the task of those who try to study and conserve it.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding