Marabou Stork Leptoptilos crumenifer Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (37)

- Monotypic

Revision Notes

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Maraboe |

| Arabic | لقلق أبو سعن |

| Asturian | Marabñ africanu |

| Basque | Marabua |

| Bulgarian | Марабу |

| Catalan | marabú africà |

| Croatian | afrički marabu |

| Czech | marabu africký |

| Danish | Marabustork |

| Dutch | Afrikaanse Maraboe |

| English | Marabou Stork |

| English (United States) | Marabou Stork |

| Finnish | afrikanmarabu |

| French | Marabout d'Afrique |

| French (France) | Marabout d'Afrique |

| Galician | Marabú africano |

| German | Marabu |

| Greek | Μαραμπού |

| Hebrew | מרבו |

| Hungarian | Afrikai marabu |

| Icelandic | Hræstorkur |

| Japanese | アフリカハゲコウ |

| Lithuanian | Marabu |

| Norwegian | marabustork |

| Polish | marabut afrykański |

| Portuguese (Angola) | Marabu |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Marabu |

| Romanian | Marabu african |

| Russian | Африканский марабу |

| Serbian | Afrički marabu |

| Slovak | marabu zdochlinár |

| Slovenian | Marabu |

| Spanish | Marabú Africano |

| Spanish (Spain) | Marabú africano |

| Swedish | maraboustork |

| Turkish | Marabu |

| Ukrainian | Марабу африканський |

Revision Notes

Peter F. D. Boesman contributed to the Sounds and Vocal Behavior page.

Leptoptilos crumenifer (Lesson, 1831)

Definitions

- LEPTOPTILOS

- crumenifer / crumenifera / crumeniferus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

115–152 cm; 4–8·9 kg; wingspan 225–287 cm. Males average larger. Only member of genus with dark iris . Immature has duller upperparts and more feathering on neck.

Systematics History

Subspecies

Distribution

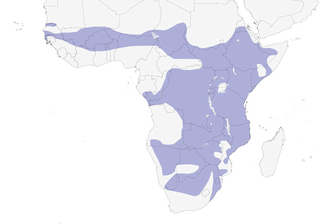

Tropical Africa from Senegal E to Eritrea, Ethiopia and W Somalia and S to Namibia and N & E South Africa (Northern Cape, Free State, KwaZulu-Natal).

Habitat

Frequents open dry savanna, grassland, swamps, river banks, lake shores and receding pools. It is seldom encountered in forest or desert. In E and C Africa numbers are frequently present near human habitation, for example in and around fishing villages . It also frequents slaughterhouses and rubbish dumps there. However, those in southern Africa tend to frequent less populated areas, such as the Okavango delta, Botswana (2). In E and S Africa commonly found around carcasses, in association with other scavengers, both avian and mammalian.

Movement

Many sedentary, especially in urbanized districts, others locally nomadic. The more northerly and southerly populations generally move towards equator after breeding. There is some southward movement, probably of non-breeders, into wetter savanna during the dry season in W Africa. Colour-ringed juveniles from the southernmost colony of the species, in Swaziland, have been resighted in their first year up to 1500km away, a few reaching Namibia, Botswana and southwestern S Africa (3).

Vagrants have reached Israel, Morocco and Spain. There are at least five Moroccan records, two of which each involved at least four individuals (4). There are recent observations of birds at large in Spain, Portugal and France: all the French records, and some of the Iberian ones, have been attributed to escapes but there is good evidence that at least some wild individuals have reached Iberia and the species is admitted to Category A in Spain (5).

Diet and Foraging

The diet is catholic and opportunistic. It often includes carrion as well as scraps of fish and other food discarded by humans , which is often scavenged at refuse dumps and abattoirs. Numbers may attend alongside vultures at carcases of large mammals killed by predators. The bill is unsuited for dismembering carcasses so it normally steals scraps from vultures or snatches up morsels that are dropped. A wide diversity of vertebrate and invertebrate prey is also taken, including fish , termites, locusts, frogs, lizards, rats, mice, snakes and birds. These last include locally both adult and young flamingos, captured at the flamingo nesting colonies. Fishing is often conducted with the submerged bill partly open and so is then probably tactile, as in Mycteria. It also fishes by sight, as do herons, and sometimes walks about in shallows, repeatedly jabbing the bill into water, as do the Ephippiorhynchus storks. It has been reported to associate at times associates with herds of large herbivorous mammals, capturing insects that the mammals disturb by their movements (6).

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

The Marabou Stork is a very silent bird away from the roosting and breeding sites. It suddenly turns into a very noisy bird however when breeding activity is in full swing , and breeding colonies can be heard from quite a distance.

Vocalizations

Vocal Development

Young utter begging calls, changing with age. Small young utter high-pitched chitters, developing after 2-3 weeks to hollow nasal squawks, later evolving into a hoarse stuttering nasal low-pitched bray. Young also already attempt to clatter bill without making much noise however (7,8). Unattended chicks repel non-parent adults uttering rapid hiccuping distress calls, and if not succesful utter loud rasping screams (7).

Vocal Array

At the nesting site, a variety of squealing, whistling, whining or mooing calls and grunts are given. Difficult to syllabize in language, most sounds can nevertheless be categorized as follows:

Squeal. A short upslurred or overslurred nasal squealing note (fundamental frequency around 2kHz, note duration ⁓0.10‒0.15s), often given in conjunction with the Mooo call of the presumed partner (as an asynchronous duet) .

Mooo. Quite variable, but typically starts as a low-pitched grunt shifting to a nasal overslurred more whistled part with fundamental frequency reaching ⁓2kHz (note duration ⁓0.3‒1.0s). A series of Mooo notes may gradually become longer in duration and less whistled, then very similar to a cow's mooing .

Hiss. A grating hissing note, typically only given once at a time.

Bill clattering and wing beats. See below.

Other. A loud nasal mwaaa was uttered by adult threatening a human intruder (7).

Geographic Variation

Has not been studied in detail, but no indication of any significant differences.

Phenology

Apart from bill-clattering in threatening situations, vocal activity is mainly concentrated around the breeding period.

Daily Pattern of Vocalizing

Mainly coincides with the daily activity during the breeding period. Hence, calls can be heard whenever parents attend the nest, and these sounds are superposed with juvenile calls once young have hatched.

Places of Vocalizing

Calls are almost exclusively heard around the nest in the breeding colony, usually in the crown of large trees but also on cliffs and in villages.

Sex Differences

Little information. Nuptial display has been described in detail (7), with specific roles for male and female, but it is not clear whether some of the accompanying vocalisations are unique to one of the sexes. It is possible that male mooing is answered by female squealing, but this is rather speculation and needs confirmation.

Social Content and Presumed Functions of Vocalizations

Vocalisations are mainly used during breeding activity. There is no clear territorial function to any vocalisation, and calls are rather uttered in the context of nuptial display, copulation, pair bonding and for communication during the care for the young. The exact function of every vocalisation type needs further clarification however.

Nonvocal Sounds

Bill clattering, producing a loud, hollow sound is used in several different situations by both sexes. During nuptial displays, pair bonding involves sharp single bill snaps and mutual bill-clattering. Equally so, during copulation, male mounts partner with open wings and clattering bill held downwards (7). Bill clattering is however also used in threatening situations away from the nest site.

Wings when taking off and landing produce low-pitched hollow beats. This is especially noticeable at the nest site when birds are manoeuvering or during nuptial display.

Breeding

The breeding season in the tropics normally begins in the dry season and ends in the rains. However, it is more variable in the equatorial zone, where dry seasons much shorter. The nesting success of the outpost population in Swaziland is closely associated with rainfall, with nests started late in the season exposed to higher rainfall and showing lower success (9). Colonies are typically of 20–60 pairs but may be as large as several thousand pairs. Nests are often mixed with those of other species, especially other Ciconiiformes. Nests are usually in trees, 10–30 m off ground; also on cliffs and even in main streets of towns. The stick nest is about 1 m wide x 30 cm deep, lined with twigs and green leaves. Clutch size is normally 2–3 eggs (1–4); incubation 29–31 days; chicks have pale grey, then white down; fledging 95–115 days. Annual productivity over a seven-year period in Uganda ranged from 0.7–1.8 chicks per occupied nest but was much lower, 0.4 chicks, at the outpost southern colony in Swaziland (2). Sexual maturity is apparently reached after at least 4 years. Only about 20% of the E African population is thought to breed in any one year. Oldest birds are thought to be over 25 years old; individuals in captivity have reached over 41 years old.

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). It is frequent, common or abundant across most of its range and is thought to be increasing overall, due to its ability to exploit the ever-increasing amounts of rubbish dumped by humans. For example, the population at Kampala city, Uganda, increased from 100 pairs in the early 1970s to nearly 1000 pairs by the mid 2000s (10). The global population in 2006 is estimated to be between 200,000 and 500,000 birds.

Estimates of its populations in the mid 1980s included: Uganda c. 5000 birds, with some 2000 in Rwenzori National Park; Kenya 1000–2000, with 797 birds counted at L Nakuru in Jan 1991. The highest available counts from W Africa pre 1992 included 600 birds in the Chad Basin; 280 birds in the Niger Basin and 402 birds counted in Cameroon in January 1991. The southernmost colony, in Swaziland, was destroyed in the 1960s to make way for a sugar cane plantation but the species has since become re-established in the country, at a new colony of 30–40 pairs at Hlane NP (3). Few breed in Zimbabwe or South Africa but large numbers occur there locally at times: for example several hundred were attracted to offal from a crocodile farm in Zimbabwe in March 2000, over 2000 were at Shinwedzi in the Kruger National Park, S Africa, in April 1999 and 1000+ were seen along the trans-Kalahari road between Lobatse and Buitpas, Botswana, in March 2000 (11, 12).

Its ugly appearance and habits may have made it less attractive to potential hunters. It is also sometimes protected both by local superstitions and by a realisation that it helpful in cleaning up carcasses and rubbish, thus helping to control disease; in the 1990s a plan to poison the birds at Kampala, Uganda, was cancelled following objections by the local people (13). CITES III in Ghana. Large numbers are kept in captivity but captive birds have only bred occasionally.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding