Redwing Turdus iliacus Scientific name definitions

Text last updated October 29, 2015

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Albanian | Tusha vetullbardhë |

| Arabic | سمنة حمراء الجناح |

| Armenian | Սպիտակահոնք կեռնեխ |

| Asturian | Malvñs roxu |

| Azerbaijani | Ağqaş qaratoyuq |

| Basque | Birigarro hegagorria |

| Bulgarian | Беловежд дрозд |

| Catalan | tord ala-roig |

| Chinese (SIM) | 白眉歌鸫 |

| Croatian | mali drozd |

| Czech | drozd cvrčala |

| Danish | Vindrossel |

| Dutch | Koperwiek |

| English | Redwing |

| English (United States) | Redwing |

| Faroese | Óðinshani |

| Finnish | punakylkirastas |

| French | Grive mauvis |

| French (France) | Grive mauvis |

| Galician | Tordo rubio |

| German | Rotdrossel |

| Greek | Κοκκινότσιχλα |

| Hebrew | קיכלי לבן-גבה |

| Hungarian | Szőlőrigó |

| Icelandic | Skógarþröstur |

| Italian | Tordo sassello |

| Japanese | ワキアカツグミ |

| Korean | 붉은날개지빠귀 |

| Latvian | Plukšķis |

| Lithuanian | Baltabruvis strazdas |

| Mongolian | Цагаан хөмсөгт хөөндэй |

| Norwegian | rødvingetrost |

| Persian | توکای پهلوسرخ |

| Polish | droździk |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | sabiá-ruivo |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Tordo-ruivo |

| Romanian | Sturzul viilor |

| Russian | Белобровик |

| Serbian | Mali drozd |

| Slovak | drozd červenkavý |

| Slovenian | Vinski drozg |

| Spanish | Zorzal Alirrojo |

| Spanish (Spain) | Zorzal alirrojo |

| Swedish | rödvingetrast |

| Turkish | Kızıl Ardıç |

| Ukrainian | Дрізд білобровий |

Turdus iliacus Linnaeus, 1758

Definitions

- TURDUS

- turdus

- iliaca / iliacus

- Iliacus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

20–24 cm; 46–80 g. Plumage is greyish-brown above, with long buffy-white supercilium ; buffy-whitish below, long lines of blackish spots radiating from throat , orange-rufous on flanks and underwing ; bill dark, yellowish base; legs pinkish-brown. Sexes similar. Juvenile is like adult, but buff-streaked above , heavily spotted below, with little orange-red. Race <em>coburni</em> is browner above and darker-spotted below than nominate.

Systematics History

Editor's Note: This article requires further editing work to merge existing content into the appropriate Subspecies sections. Please bear with us while this update takes place.

In past, sometimes referred to as T. musicus, but this name was officially suppressed (1). Date of species name has often erroneously been listed as 1766, as in HBW and elsewhere (2). Two subspecies recognized.Subspecies

Redwing (Icelandic) Turdus iliacus coburni Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Turdus iliacus coburni Sharpe, 1901

Definitions

- TURDUS

- turdus

- iliaca / iliacus

- Iliacus

- coburni

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Redwing (Eurasian) Turdus iliacus iliacus Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Turdus iliacus iliacus Linnaeus, 1758

Definitions

- TURDUS

- turdus

- iliaca / iliacus

- Iliacus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

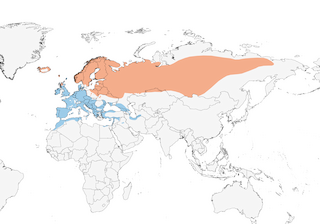

Distribution

Editor's Note: Additional distribution information for this taxon can be found in the 'Subspecies' article above. In the future we will develop a range-wide distribution article.

Habitat

Breeds in forest-open country mosaic in lowlands and relatively low hills, with preference for mid-successional conditions, especially in river basins and on floodplains: open deciduous or mixed forest margins with fields and mires, clearings in primary forest, regenerating managed forest at tall bushy stage with considerable understorey, shoreline thickets, tundra willow (Salix) and birch (Betula) scrub, scrubby semi-open cultivated sites, parks and gardens , thinned woodland with grassy areas around buildings; in Iceland and boreal montane regions breeds in rocky areas with often only sparse scrub. Recent colonists in Scotland breed in hedgerows, woodland edge, hillside birch woods and grounds of large private houses, also in swampy alder (Alnus) woods. Winters in open woodland, orchards and scrub thickets, wherever berry-bearing bushes and grassy areas in proximity; in Britain prefers dense even grassland as found in parks and on playing fields, usually keeping close to tall cover and frequently moving between the two, also stubble and fields of root vegetables with thorn hedges and open woodland, and penetrates urban gardens and city centres in colder weather (when may also move to coastal areas). In more S areas of winter range may reach higher elevations than elsewhere, e.g. in Morocco (where uncommon and irregular) occupies orchards, olive groves and cedars in High Atlas.

Movement

Migratory; a few resident on Icelandic coast, Norwegian coast, in Scotland and in S Baltic region. Distance travelled varies with origin and with severity of seasonal conditions; little winter site-fidelity. Migrates at night, usually in loose but extensive flocks. Almost entire population winters inside W Palearctic, so that birds breeding in extreme E part of range fly WSW at least 6500 km to reach nearest wintering grounds. Race coburni largely quits Iceland and Faeroes, passing through Fair Isle (off N Scotland) slightly later than nominate, some perhaps making long direct flight to Iberia; winter quarters in Britain, Ireland, W France, Spain and Portugal, birds from W Iceland mainly S of Loire valley, in France, those from E Iceland N of it. Other W Palearctic populations travel to C & S of region on three main migratory routes: (1) North Sea/British route, often via W Norway, (2) N/W continental Europe route via North Sea coast to Atlantic France and Iberia, (3) S/E continental Europe route via R Danube and R Po to W Mediterranean; some move SE, as Finland the main source of ringed individuals wintering in E Mediterranean and between Black and Caspian Seas. Vacates Sweden and Norway late Sept to mid-Nov, apparently on broad front. Much farther E, in SC Siberia, autumn departure much earlier, from end Aug, with only few left late Oct, while dates from farther W in Russia mainly in Sept to mid-Oct; passage around Kharkov, in Ukraine, starts end Sept, main passage end Oct, and in Caucasus lasts mid-Sept to mid-Nov. In Europe, heaviest winter concentrations in SW France, where arrival from late Sept, some moving into Iberia in Nov in some years but not until Jan in others; arrival in Italy mainly from mid-Oct to late Nov (peak mid-Nov), with much weaker spring return pattern; most ringed individuals derive from Baltic region but great majority there and in W Mediterranean may originate in Siberia. Uncommon irregular to regular winter visitor N Africa: Morocco mid-Oct to mid-Mar (most movement mid-Oct to mid-Nov, late Feb to mid-Mar), Algeria and Tunisia Nov–Mar, Libya Jan–Feb, Egypt late Oct to late Apr. Variously absent to fairly common in winter in Israel, passage (including winterers) mainly late Nov and Dec, departure mainly early Mar. Spring migration in France exhibits two peaks, in late Feb and in mid-Mar, but unclear whether two different breeding populations, two age-classes or different sexes. Spring migration in E Britain begins late Feb to early Mar, lasts into May; arrival S Norway end Mar or early Apr. Schedule of spring movements in E of range related both to latitude and to longitude, with birds moving out of Caucasus region Mar–Apr, passing through Ukraine late Mar or early Apr, arriving Arkhangel’sk and C Ural Mts late Apr, reaching Tomsk last week Apr or first week May. Fidelity of adults to breeding area higher than that of young to natal area: in ringing study in Norway, 21% of adults and 4% of nestlings returned in following season to study area in Oslo. Vagrants recorded in many areas, e.g. Pakistan and Afghanistan. One Southern Hemisphere record, in South America: a dead bird found in Dec 2001 on a research vessel 150 km off the coast of Espírito Santo state, SE Brazil (3).

Diet and Foraging

Invertebrates , also seeds and berries in autumn and winter. Animal foods include adult and larval beetles (Coleoptera) of at least eight families, adult and larval hymenopterans (ants, ichneumons, sawflies), adult and larval flies (Diptera), caterpillars, bugs (Hemiptera), orthopterans (crickets, mole-crickets), dragonflies (Odonata) and mayflies (Ephemeroptera), spiders, sandhoppers (Amphipoda), small crabs, millipedes (Diplopoda), small molluscs, earthworms and marine worms. Plant foods include fruits and/or seeds of cotoneaster (Cotoneaster), hawthorn (Crataegus), heaths (Ericaceae), strawberry (Fragaria), alder buckthorn (Frangula), ivy (Hedera), holly (Ilex), juniper (Juniperus), apple (Malus), pine (Pinus), cherry (Prunus), pear (Pyrus), buckthorn (Rhamnus), currant (Ribes), rose (Rosa), madder (Rubia), bramble (Rubus), elder (Sambucus), rowan (Sorbus), yew (Taxus), viburnum (Viburnum) and vine (Vitis), also various root crops. In spring and summer wide range of invertebrates taken, depending on local availability, but few studies. Autumn and winter diet much better known. In SW Iceland, prior to autumn migration, c. 800,000 fruits/ha available, mostly (c. 90% of fresh weight) Empetrum nigrum, with Vaccinium uliginosum, Arctostaphylos uva-ursi, Vaccinium myrtillus and Rubus saxatilis; E. nigrum most important component of diet (70–80% of fruits ingested), followed by V. uliginosum (c. 20%), while R. saxatilis avoided; mean width of seeds in droppings suggests preference for large E. nigrum fruits (having higher pulp-to-seed weight ratio). Autumn migrants on Holy I, in NE England, took mainly snails, and in three areas of S Britain 86% of 166 records of fruit-eating involved hawthorn; birds in field in E Britain, Oct–Feb, took 67% surface items and 33% subsurface items (in contrast to T. pilaris). In winter, diet in S France fleshy fruits (grapes, juniper berries, madder), gastropods and arthropods; in S Spain, 88 stomachs of birds wintering in olive groves held 86% vegetable matter by biomass (of which 97% olives), remainder made up by beetles and larvae, also the crop-damaging homopterans Euphyllura olivina and Chrysomphalus dictyospermi. Food brought to nestlings in N Sweden largely earthworms (77–96% of 3199 feedings over five years), supplemented mainly by flies and caterpillars; of 102 feedings in S Finland, 67% small earthworms, 27% adult insects (mainly mayflies, also beetles, dragonflies, flies) and 5% insect larvae. Forages mostly on ground and in low bushes.

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Song , by male from prominent high perch, a series of simple and rather monotonous phrases , each sweet and descending with final softer, twittery, drier, varied burbling chatter, “trúi-trúi-trúi trip-trr-bziriri-rrit”; at least 27 dialects noted in areas of S Norway, where males sing one particular dominant song type. Subsong, by flocks on migration and in winter, a low twittering chorus. Calls include distinctive drawn-out high-pitched buzz, “dssssi” or “srieh”, as contact and hence irregularly, but very frequently at night on migration (becoming, in other contexts, a clearer “shriii”); also abrupt “chup” or “chittick” when feeding or going to roost in winter, hard sharp rattling “trrrt trrrt trrrt” when nest in danger, and loud chuckling “di-dju-dju-dju”.

Breeding

Early Apr to late Jul, with some latitudinal variation, from mid-May in Iceland; double-brooded. Generally solitary, but in optimal habitats may form loose colonies (or territories so small that appearance colonial), e.g. 8 nests in 0·075 ha of young spruce (Picea) in SE Finland (average nesting territory less than 100 m²); sometimes group nests within T. pilaris colony, and occasionally nest-site in close proximity to T. merula and T. philomelos. Nesting territory less than 1 ha and often less than 0·5 ha, but forages sometimes beyond borders in additional area up to 1·5 ha. Nest a bulky cup of grass , moss and twigs , bound with mud and bits of vegetation, lined with fine grass stems and leaves, placed on ground in thick vegetation or low in bush or tree or on rotten stump; of 451 nests in Swedish Lapland, 34% in tree, 28% on ground in vegetation, 17% in stump, 13% in juniper bush, and 8% on ground under juniper bush; 59% of 360 nests 0–0·5 m above ground, 23% 0·5–1 m up, 13% 1–2 m up, 5% higher. Eggs 4–6, rarely 3 or 7, pale blue to greenish-blue with fine reddish-brown speckling and mottling; incubation period 10–14 days, mostly 12–13 days; nestling period 12–15 days; post-fledging dependence 14 days; male may continue to feed young while female initiates second clutch. Of 259 nests in Swedish Lapland, 32% lost, mainly to crow (Corvidae) predation, hatching success of 286 eggs 81%, fledging sucess 69%, overall success 62%; in Finland, hatching success 69%, fledging success 73%, overall success 50%. Causes of mortality of ringed individuals in NW Europe are domestic predator 12%, human-related (accidental) 12%, human-related (deliberate) 57%, other 19%.

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened. Currently considered Near Threatened. Generally common. Global population very roughly calculated to be c. 65,000,000–130,000,000 individuals BirdLife International (2015) Species factsheet: Turdus iliacus. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 27/10/2015. . Total population in Europe in mid-1990s estimated at 4,997,089–6,515,929 pairs (great majority in Fennoscandia, particularly Finland), with additional 100,000–1,000,000 pairs in Russia. By 2000 total European population (including European Russia) revised to 16,000,000–21,000,000 pairs and considered generally stable. In 2000s, estimated 13,200,000–20,100,000 pairs in Europe, of which 10,000,000–15,000,000 in Russia, 1,300,000–1,800,000 in Finland, 1,000,000–1,500,000 in Norway, 510,000–1,190,000 in Sweden, 100,000–200,000 in Iceland (race coburni), 100,000–150,000 in Estonia and 45,000–100,000 pairs in Belarus (4). Numbers, however, locally or regionally very variable owing to effects of harsh and mild winters, and of unfavourably cold summers, such that Finnish population fell from 2,700,000 pairs 1973–1977 to 1,500,000 pairs 1986–1989. Apart from variable weather and perhaps long-term climate-change, the only threat is illegal trapping in the Mediterranean (5). Since 1930, steady expansion S through Baltic states and into Ukraine; since 1960s, outposted breeding population in Scotland. Nevertheless, European population is estimated to have decreased by 25–30% over last 15·6 years (three generations); breeding population in European Russia has declined by >20% since 2000 and by >30% since 1980 (4) BirdLife International Globally Threatened Bird Forums . Monitored European population shows similar long-term and short-term trends (6) BirdLife International Globally Threatened Bird Forums . Only c. 40% of the species’ global breeding range is in Europe, but European Russian trends are thought likely to be mirrored to at least some degree E of Urals BirdLife International Globally Threatened Bird Forums . Density in optimal habitat may reach 0·7–1·2 pairs/ha (70–120 pairs/km²), and in suburban parks in Russia may extrapolate to 50–250 pairs/km²; normally much lower, 0·06–0·4 pairs/ha (6–40 pairs/km²), and always lower in conifers than in deciduous tracts; in S Finland, 18 pairs/km² overall, ranging from 3·3 in Vaccinium-floored mixed woodland to 94 in grassy-floored broadleaf woodland. Not considered of conservation concern until 2015, when evidence of declines led to listing as Near Threatened.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding