Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (50)

- Monotypic

Revision Notes

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Asturian | Mazaricu de Bartram |

| Basque | Kuliska buztanluzea |

| Bulgarian | Прерийник |

| Catalan | territ cuallarg |

| Croatian | prerijska prutka |

| Czech | bartramie dlouhoocasá |

| Danish | Bartramsklire |

| Dutch | Bartrams Ruiter |

| English | Upland Sandpiper |

| English (United States) | Upland Sandpiper |

| Finnish | preeriakahlaaja |

| French | Maubèche des champs |

| French (France) | Maubèche des champs |

| French (French Guiana) | Maubèche des champs |

| Galician | Mazarico do campo |

| German | Prärieläufer |

| Greek | Μπαρτράμια |

| Hebrew | ביצנית זנבתנית |

| Hungarian | Hosszúfarkú cankó |

| Icelandic | Sléttulæpa |

| Italian | Piro piro codalunga |

| Japanese | マキバシギ |

| Lithuanian | Bartramija |

| Norwegian | præriesnipe |

| Polish | preriowiec |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | maçarico-do-campo |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Maçarico-do-campo |

| Romanian | Fluierar cu coadă lungă |

| Russian | Прерийный кроншнеп |

| Serbian | Crnokrili sprudnik |

| Slovak | bartrámia dlhochvostá |

| Slovenian | Travničar |

| Spanish | Correlimos Batitú |

| Spanish (Argentina) | Batitú |

| Spanish (Chile) | Batitú |

| Spanish (Costa Rica) | Pradero |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Ganga |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Praderito Colilargo |

| Spanish (Honduras) | Playero Sabanero |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Zarapito Ganga |

| Spanish (Panama) | Pradero |

| Spanish (Paraguay) | Batitú |

| Spanish (Peru) | Playero Batitú |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Playero Pradero |

| Spanish (Spain) | Correlimos batitú |

| Spanish (Uruguay) | Batitú |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Tibi-Tibe |

| Swedish | piparsnäppa |

| Turkish | Uzun Kuyruklu Düdükçün |

| Ukrainian | Бартрамія |

Revision Notes

Steven G. Mlodinow revised the account. Fernando Medrano contributed to the Migration, Habitat, and Conservation pages as part of a partnership with Red de Observadores de Aves y Vida Silvestre de Chile (ROC).. Peter Pyle contributed to the Plumages, Molts, and Structure page. Arnau Bonan Barfull curated the media. Eliza Wein updated the distribution map. JoAnn Hackos, Daphne R. Walmer, and Robin K. Murie copyedited the account.

Bartramia longicauda (Bechstein, 1812)

Definitions

- BARTRAMIA

- bartramia / bartramii / bartramius

- longicauda

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

On cool August nights you can hear their whistled signals as they set wing for the pampas, to prove again the age-old unity of the Americas. Hemisphere solidarity is new among statesmen, but not among the feathered navies of the sky. A. Leopold — A Sand County Almanac (1).

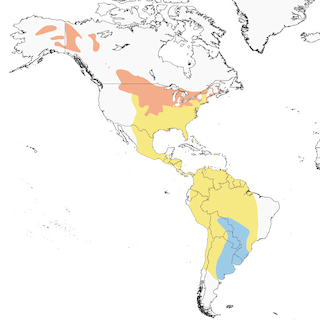

The Upland Sandpiper is a hallmark species of the North American Great Plains, across which its evocative "wolf-whistle" can be heard throughout hot summer days and warm summer nights. Unlike most shorebirds, the Upland Sandpiper eschews wetlands and is almost completely terrestrial. Indeed, it is nearly an obligate grassland species, so much so that is it often considered an indicator species of tall-grass prairie health. Its preference for open spaces led to an extensive eastward range expansion as European settlers cleared eastern forests, but that trend reversed, starting around 1870, due to a boom in market and sport hunting—hunting with no bag limits or closed seasons. Boxcars filled with Upland Sandpiper were shipped to markets. The enforcement of the Migratory Birds Convention Act of 1916 curbed but did not stop this decline, likely due to habitat loss, as ever more grasslands were broken by the plow and crops planted. Fortunately, this trend appears to have reversed, with Breeding Bird Survey data showing an overall 1.4% annual population increase from 1966–2005. Despite the overall upward trend, ongoing habitat loss has led to a decimation of many eastern populations, with the species disappearing as a breeder from some states, and nesting in other states relying heavily on airfields for habitat. That said, the Upland Sandpiper has adapted to novel habitats at some locations and is now relatively common in the blueberry barrens and peatlands of Maine, New Brunswick, and Quebec. Far away from the classic Great Plains haunts, it also breeds in Alaska, Yukon, and Northwest Territories, using open grasslands in alluvial floodplains and moist/wet alpine tundra. The current global population estimate is 750,000 birds.

After breeding, largely in July and August, the Upland Sandpiper embarks upon a relatively leisurely— but lengthy—voyage to southern South America, a jaunt of some 5,000–10,000 km for birds breeding in the contiguous United States and rather longer for those birds breeding near the Arctic. The primary wintering grounds are the grasslands and agricultural fields of northeastern Argentina, Uruguay, southern Brazil, Paraguay, and eastern Bolivia, where the sandpipers generally reside from October/November into March. Northbound migration is a much more hurried affair, averaging perhaps one third the duration of the southbound migration, with birds arriving on their breeding grounds largely in April and May. Illustrative of the spring migration's rush, one northbound PTT-tagged sandpiper flew 7,581 km without pause. Such long distance capabilities mean that occasionally individuals wander far, far away from their intended destination, with records coming from as far afield as Australia, Guam, and Deception Island off the coast of Antarctica.

The Upland Sandpiper often breeds in loose colonies, is generally monogamous, and typically lays four eggs in a shallow scrape. Eggs are brooded for 3–4 weeks before hatching, and the freshly hatched chicks are precocious. Within a week of hatching, those chicks are actively feeding themselves, and within a month or so, they are capable of flight.

The Upland Sandpiper has had a number of common names. Coues initially called it Bartramian Tattler in 1878 (Bartram, in both common and scientific names, honors Alexander Wilson's mentor, William Bartram), a name that was changed by the American Ornithologists' Union to Bartramian Sandpiper in 1886 and then to Upland Plover in 1910, presumably because its habits, habitat, and appearance bore a fair resemblance to grassland plovers. The species' current and more appropriate name was adopted by the American Ornithologists' Union in 1973, although one could argue that Upland Curlew would have been a better choice, because Bartramia and Numenius are sister genera.

Those wishing a glimpse into the species as it was experienced in the 19th century should read the writings of Elliott Coues (2), a surgeon and naturalist on the U.S.-Canada boundary survey in 1873 and 1874, and those by W. H. Hudson (3, 4), who lived on the Argentine pampas until 1874. The first extensive life-history of the Upland Sandpiper, succinct and packed with information, was written by Buss and Hawkins based on observations in Wisconsin during the late 1930s (5).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding