White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla Scientific name definitions

Revision Notes

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Albanian | Shqiponja e detit |

| Arabic | عقاب البحر بيضاء الذيل |

| Armenian | Սպիտակապոչ արծիվ |

| Asturian | Pigargu raublancu |

| Azerbaijani | Ağquyruq dəniz qartalı |

| Basque | Itsas arrano buztanzuria |

| Bulgarian | Морски орел |

| Catalan | pigarg cuablanc |

| Chinese | 白尾海鵰 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 白尾海雕 |

| Croatian | štekavac |

| Czech | orel mořský |

| Danish | Havørn |

| Dutch | Zeearend |

| English | White-tailed Eagle |

| English (United States) | White-tailed Eagle |

| Faroese | Havørn |

| Finnish | merikotka |

| French | Pygargue à queue blanche |

| French (France) | Pygargue à queue blanche |

| Galician | Pigargo europeo |

| German | Seeadler |

| Greek | (Ευρωπαϊκός) Θαλασσαετός |

| Hebrew | עיטם לבן-זנב |

| Hungarian | Rétisas |

| Icelandic | Haförn |

| Italian | Aquila di mare |

| Japanese | オジロワシ |

| Korean | 흰꼬리수리 |

| Latvian | Jūras ērglis |

| Lithuanian | Jūrinis erelis |

| Malayalam | വെള്ളവാലൻ കടൽപ്പരുന്ത് |

| Mongolian | Цагаан сүүлт нөмрөг бүргэд |

| Norwegian | havørn |

| Persian | عقاب دریایی دم سفید |

| Polish | bielik |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Pigargo |

| Romanian | Codalb |

| Russian | Орлан-белохвост |

| Serbian | Belorepan |

| Slovak | orliak morský |

| Slovenian | Belorepec |

| Spanish | Pigargo Europeo |

| Spanish (Spain) | Pigargo europeo |

| Swedish | havsörn |

| Thai | นกอินทรีหางขาว |

| Turkish | Ak Kuyruklu Kartal |

| Ukrainian | Орлан-білохвіст |

Revision Notes

Shawn M. Billerman revised the Systematics page, and standardized the account with Clements taxonomy. Peter Pyle contributed to the Plumages, Molts, and Structures page.

Haliaeetus albicilla (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- HALIAEETUS

- albicilla / albicillus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

74–92 cm (1); male 3,100–5,400 g, female 3,700–6,900 g (1); wingspan 193–244 cm (1). White tail, yellow bill , and yellow irides as in Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), but head and neck pale buff rather than pure white, contrasting much less with rest of plumage; upperparts fairly pale, wing coverts and upper back yellowish-brown; tail wedge-shaped. Female averages ca. 15% larger and 25% heavier than male (1). Juvenile blackish-brown, with tail, head, bill and irides all dark; whitish markings on axillaries; gradually attains adult plumage over 5–6 years, but tail not white until 8th year; bill yellow after 4–5 years.

Plumages

The White-tailed Eagle has 10 full-length primaries (numbered distally, from innermost p1 to outermost p10), 14 to 15 secondaries (numbered proximally, from innermost s1 to outermost s11 or s12, and three tertials numbered from distally, from t1 to t3), and 12 rectrices (numbered distally on each side of the tail, from innermost r1 to outermost r6. Accipitrid hawks, including the White-tailed Eagle, are diastataxic (see 2), indicating that, through evolution, a secondary has been lost between what we now term s4 and s5. Wings are long and broad, with p8–p7 the longest, followed by p6, p9, p10, and p5 (3), with p5–p10 notched on the outer web and p5–p9 emarginated on the inner web as in the congeneric Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) (4). The following descriptions are based on those of Dement'ev and Gladkov (5), Cramp and Simmons (3), and Forsman (6), along with examination of Macaulay Library images; see these references, Forsman (7), and Pyle (4) for age-determination criteria in Haliaeetus eagles. See Molts for molt and plumage terminology. Sexes are alike in all plumages; definitive appearance is usually assumed at the Fifth to Seventh Basic Plumage (3, 6).

Natal Down

Natal down is present primarily from March to June, when the young are in the nest. Hatchlings appear to be covered with gray prepennae. In Bald Eagle the first down is replaced beginning at days 9 to 11, with a second (preplumulae) down that is thick, woolly, and darker gray to slate in color (8, 9) and this appears to be the case for White-tailed Eagle as well (see image below). The gray prepennae down may remain longest on the nape and wings (see image).

Juvenile (First Basic) Plumage

Present primarily from July to December or July to June, depending on presence of Preformative Molt (see Molts). Juveniles are generally dark brown to blackish brown throughout, with variable amount of buff to whitish mottling, particularly among upperwing coverts, underwing coverts, and underparts. Feathers of upperparts with pale bases that can be exposed when feathers are ruffled. Scapular centers may be washed gray. Upperwing coverts are cinnamon with variably broad dark tips creating mottled buff panels across the wings; uppertail coverts also buff to cinnamon with dark tips. Rectrices with white centers, variably mottled dark brown, and with broad dark fringes. Remiges dark with pale centers, especially to the secondaries. Underparts and underwing coverts dark brown, the throat usually paler; white feather bases are usually evident creating lightly mottled pale appearance to these tracts. Juvenile remiges and rectrices are longer and more tapered or pointed at the tips than basic feathers.

Formative Plumage

This plumage has not been described for White-tailed Eagle but is found in most accipitrid hawks including Bald Eagle (10), where it is present primarily from December into August. In that species, Formative Plumage is similar to Juvenile Plumage but with up to 20% of the upperpart and underpart body feathers replaced, appearing newer and darker (upperparts) or with increased white markings (underparts) than the remaining older and faded juvenile feathers. By the first spring the crown may become bleached to buffy brown, contrasting with blackish-brown auriculars. Formative feathers typically grown in well before commencement of the Second Prebasic Molt and can be replaced again at that molt (10).

Second Basic Plumage

This is generally equated with "First Immature" plumage in life-cycle terminology (see Molts). Present primarily from October (when fresh) to July (when worn) with transitional (molting) birds present from April to November, resulting in variable plumage appearance throughout the second molt cycle. Second Basic Plumage is similar to Juvenile plumage except body feathering more mottled pale or whitish due to a mixture of juvenile and variably worn formative feathers that are more extensively white at the bases. Feathers of the nape, back, uppertail coverts, and underparts are primarily white with variably dark feather tips, creating a largely mottled white appearance. The upperwing and underwing coverts have increased white mottling. Flight-feather molt is incomplete, with with 4 to 7 juvenile outer primaries and 3 to 12 juvenile secondaries (among s2–s4 and s7–s13) usually retained, very worn, and contrasting with fresher, broader, and shorter replaced inner primaries and other secondaries; juvenile secondaries are typically > 20 mm longer than basic secondaries (3). These mixed feather generations can result in an uneven trailing edge to the wing in flight. The rectrices are usually completely replaced during this molt and are broader and more truncate than juvenile feathers, with cleaner white centers but still showing broad dark fringes; look for 1 or more juvenile rectrices to occasionally be retained, perhaps most often among r2 and r5.

Third Basic Plumage

This is generally equated with "Second Immature" plumage in life-cycle terminology (see Molts). Present primarily from October (when fresh) to July (when worn) with transitional (molting) birds present from May to November, resulting in variable plumage appearance throughout the third molt cycle. Third Basic plumage can be very similar to Second Basic Plumage with some darker body feathers may molt in, creating less of a white-mottled appearance. Most birds retain some juvenile secondaries and (less often) juvenile primaries, the best means of identifying Third Basic Plumage. One to 3 or more juvenile outer primaries (among p8–p10) and 1 to 6 or more juvenile secondaries among s3–s4 and s8–s11 can be retained, along with varying numbers of both second-basic and third-basic feathers molted in sequence (see images below). Retained juvenile secondaries are browner and stand out for their length. Some faster-maturing birds in Third Basic Plumage may have replaced all juvenile remiges and are inseparable from other predefinitive plumages with dark in the rectrices (e.g., Fourth through Seventh Basic Plumages, below). On the other hand, some slower-maturing individuals in Fourth Basic Plumage may continue to retain juvenile feathers; study is needed on molt-retention patterns in these cases.

Fourth Basic through Seventh Basic Plumages

These are generally equated with "Third Immature" to "Sixth Immature" plumages in life-cycle terminology (see Molts). Present primarily from October (when fresh) to July (when worn) with transitional (molting) birds present from May to November, resulting in variable plumage appearance throughout the third molt cycle. Some to most individuals in Fourth Basic Plumage and most in Fifth through Seventh Basic Plumage resemble Definitive Basic Plumage, with no juvenile remiges remaining, except that the head can be darker brown, variable amounts of pale or white mottling occur through the underpart feathering (including undertail coverts) and underwing coverts, and variable amounts of dark fringing or markings remaining in the rectrices. Primaries and secondaries with 2 to 4 generations or "sets," in Staffelmauser (or stepwise) patterns, those sets among the primaries identified by boundaries between more-worn distal and fresher adjacent proximal feathers (11). Occasional birds in Sixth and some birds in Seventh Basic Plumages may be indistinguishable from Definitive Basic Plumage (detailed study on known-age birds needed). The number of sets and exact patterns of replacement from Staffelmauser may help distinguish birds in these plumages but otherwise variation in maturation rates usually precludes accurate assignment to a specific predefinitive plumage.

Definitive Basic Plumage

Definitive Basic Plumage is generally equated with "Adult" plumage in life-cycle terminology (see Molts). Head and neck pale grayish-buff with diffuse duskier streaking and often slightly darker brown feathers from the lores to the auriculars forming an indistinct mask. The paler head contrasts with darker brown upperparts, the feathers fringed pale forming scaled appearance when fresh. Shorter uppertail coverts dark, sometimes mottled white; longer uppertail coverts white with dark bases and tips; rectrices white, the (usually obscured) basal portions mottled dark. Upperwing coverts pale grayish with dark fringes to darker brown, the greater coverts often darker. Multiple generations and/or protracted molts can result in variation in wear and fading to the upperpart feathers and upperwing coverts, creating a highly mottled appearance; feathers can become yellowish brown when worn. Remiges dark brown, the middle primaries (~p4–p9) with pale gray portions to inner webs at the bases. Breast dark brown, contrasting with paler buff-brown of head including chin, throat, and often upper breast; remaining underparts and underwing coverts variably dark brown or mottled with paler brown or (sometimes) visible whitish feather bases. Basic remiges show 2 to 4 sets of basic feathers in Staffelmauser patterns (12, 4; see Molts); replacement sets of primaries are identified by the presence of a worn feather immediately distal to a fresher proximal feather, while secondaries show mixed generations of feathers in various sequences (13, 6, 14, 15, 11, 4).

Molts

General

Molt and plumage terminology follows Humphrey and Parkes (16), as modified by Howell et al. (17). Under this nomenclature, terminology is based on evolution of molts along ancestral lineages of birds from ecdysis (molts) of reptiles, rather than on molts relative to breeding, location, or time of the year, the latter generally referred to as “life-cycle” molt terminology (18). In north-temperate latitudes and among passerines, the Humphrey-Parkes (H-P) and life-cycle nomenclatures correspond to some extent but terms are not synonyms due to the differing bases of definition (19). Prebasic molts often correspond to “post-breeding“ or “post-nuptial“ molts, preformative molts often correspond to “post-juvenile“ molts, and prealternate molts often correspond with “pre-breeding“ molts of life-cycle terminology; however, for diurnal raptors, the Preformative Molt is undefined in many species and the Second Prebasic Molt is often referred to as the "post-juvenile" molt (20). In general, for species that suspend prebasic or preformative molts for migration or undergo extensive molts on winter grounds, there is often a lack of correspondence between H-P and life-cycle terms (19). The terms prejuvenile molt and juvenile plumage are preserved under H-P terminology (considered synonyms of first prebasic molt and first basic plumage, respectively) and the former terms do correspond with those in life-cycle terminology. As with the congeneric and closely related Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), the White-tailed Eagle appears to exhibit a Modified Basic Strategy (c.f. 17, 21), including incomplete prebasic molts and a limited preformative molt in some individuals, but no prealternate molts (5, 22, 6; cf. also 20, 15, 4).

Second and later prebasic molts exhibit a Staffelmauser (or stepwise) sequence and pattern of flight-feather replacement (12, 13, 23, 14, 11, 4). Replacement proceeds distally among the primaries (p1 to p10) and their corresponding primary coverts; proximally from secondaries s5 and s1; and bilaterally from the second tertial (t2). During Staffelmauser, prebasic molts are incomplete, with each subsequent molt continuing where the previous molt arrested and new waves often initiated, resulting 2–4 waves and generations of basic feathers by the time definitive appearance is achieved (see images below and under Second and later Basic Plumages). Molt of rectrices in Accipitridae proceeds most often in the sequence r1–r6–r3–r4–r2–r5 (4), but variation in the order of rectrix molt also occurs; up to 6 rectrices can be retained, resulting in the presence of up to two feather generations during second and later cycles. Prebasic Molts occur primarily following breeding, from June into November, but sporadic continuation of molt through February or later can occur.

Prejuvenile (First Prebasic) Molt

The only complete molt. It occurs primarily from April into July in the nest. Little detailed information on this molt for White-tailed Eagle. In Bald Eagle, flight feathers emerge at 2 to 3 weeks of age; body feathers begin emerging with the humeral tract at day 24 to 31, followed by feathers on head and back at four to five weeks, feathers of the lateral ventral surface at 4 to 6 weeks, and feathering on tarsi last at 6 to 8 weeks; Juvenile Plumage completes growth at about 11 to 14 weeks of age, usually postfledging, though outer primaries and rectrices may require two or more additional weeks to complete growth (8, 24).

Preformative Molt

The Preformative Molt in Accipitrid raptors has only recently recognized; it occurs primarily from December into April and includes body feathers scattered over the head and body (10). This molt has sometimes been considered early commencement of Second Prebasic Molt but appears to be a separate inserted first-cycle molt, homologous with the preformative molt of other raptors and involving feathers that are replaced again during the Second Prebasic Molt (10). In Bald Eagle, Preformative Molt includes up to 40% of body feathers being replaced by May; examination of Macaulay Library images suggests that this molt occurs in White-tailed Eagle, but that the percentage of feather replacement may be less (see images under Formative Plumage).

Second Prebasic Molt

Often equated with the "Post-juvenile" molt but sometimes the "First Immature" molt in life-cycle terminology. Occurs primarily from April into November of the second calendar year, averaging earlier than this molt in adults due to lack of breeding constraints. It includes some to most or all body feathers, upperwing secondary coverts, and rectrices. Some juvenile rump feathers and greater coverts may be retained as well. Three to 6 inner primaries (and corresponding primary coverts) and 6–11 secondaries (inlcuding the tertials) are usually replaced, leaving 3 to 6 juvenile outer primaries (and their coverts) and 4 to 9 or more juvenile secondaries among s2–s4 and s7–s12 are retained, similar to the extent of this molt in Bald Eagle (15, 4). Molt of the tertials commences shortly after p1 is dropped, and molt of the outer secondaries (s1 or s5) commences sometime in midsummer (May to July), after molt of primaries has reached p4 or p5. Reports that this or subsequent Prebasic Molts can occasionally be complete requires verification.

Third Prebasic Molt

Often equated with the "First Immature" or "Second Immature" molt in life-cycle terminology. Incomplete, primarily April to November. Similar in timing and extent to the Definitive Prebasic Molt, although may commence earlier, on average, due to the lack of breeding constraints in most two-year-old eagles. Includes most to all body feathers and upperwing secondary coverts, and typically 3 to 4 or more primaries (and corresponding primary coverts), 6 to 8 or more secondaries, most to all rectrices (3,7). Molt of flight-feathers resumes where the Second Prebasic Molt arrested and can also include the commencement of new molt waves at p1, s1, s5, the tertials, to continue a Staffelmauser pattern among remiges (11,4). Sometimes, 1 to 3 juvenile primaries (among p8–p10) and 1 to 6 secondaries (among s3–s4 and s7–s10) can be retained after the Third Prebasic Molt, but all juvenile body feathers and rectrices are typically replaced by this molt, those being retained being second basic.

Definitive Prebasic Molt

Often equated with the "Adult" molt in life-cycle terminology. By the Fourth Prebasic Molt strategies have stabilized, matching the Definitive Prebaisc Molt, even though definitive plumage appearance is not achieved by some birds until after the Fifth–Seventh Prebasic Molts (see Plumages). Definitive Prebasic Molt is incomplete and occurs primarily from May or June into December, although it can extend through February in some individuals, perhaps more commonly in those birds that breed successfully (leaving less time to molt) and winter in the southern portions of the range. As in Bald Eagle, the molt of flight feathers can likely commence on the breeding grounds (including during incubation at nest sites), complete on the wintering grounds, and can be suspended for chick-feeding, migration, or for periods in early winter (15, 4). Extent of remex replacement as in Third Prebasic Molt but more variable, with fewer feathers replaced in successfully breeding individuals than those that skip or fail breeding and have more time to molt. Replacement of flight feathers typically proceeds in 2 to 4 waves through the wing in Staffelmauser patterns, resulting in 2 to 4 "sets" of feathers following completion of molt (11, 4). Rectrices at various positions can be retained in birds that molt fewer remiges, resulting in 2 generations of feathers, often among r2 and r5 but at other positions following consecutive incomplete rectrix molts.

Bare Parts

Based on information in Dement'ev and Gladkov (5), Cramp and Simmons (22), and Forsman (6), along with examination of Macaulay Library images; for reference see those according to age in the Plumage section.

Bill, Cere, and Gape

In adults, the bill and cere are bright yellow. In nestlings, the cere can be dusky gray and the bill is mostly black; the gape can be swollen and bright yellow (see image under Juvenile Plumage). During the first year the cere becomes pale yellow before attaining brighter yellow color of adults. The bill remains mostly black, variably transitioning to yellow over the first 2–4 years.

Iris

In adults the iris is bright and pale yellow to grayish-yellow. In nestlings and juveniles the iris is dark, gradually becoming yellowish-brown, brownish-yellow, and dull yellow over the first 3–4 years before reaching the coloration of adults.

Tarsi and Toes

At all ages the tarsi and toes are yellow, perhaps being duller or pinker in nestlings. The claws are black.

Systematics History

Close relationship with Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) supported by genetic data (25, 26, 27), with the two sometimes considered to form a superspecies (e.g., 28, 29). Greenland population sometimes separated as subspecies groenlandicus on grounds of larger average size as here (29, 30), but species varies clinally, increasing in size from southeast to northwest, so many authorities treat the species as monotypic (e.g., 28, 1).

Subspecies

Haliaeetus albicilla groenlandicus Scientific name definitions

Systematics History

Falco Albicilla Linnaeus, 1758, Systema Naturae, ed. 10, p. 89. Type locality given as Europe (31).

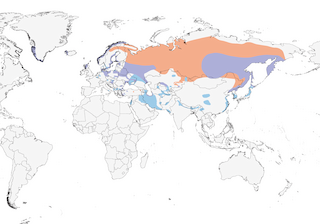

Distribution

Western Iceland; northern and central Eurasia south to Greece and Turkey, southern Caspian Sea, Lake Balkhash, and northeastern China. Winters south to northern Mediterranean, Israel, Persian Gulf, Pakistan, northern India, northern Myanmar, and southeastern China.

Haliaeetus albicilla groenlandicus Brehm, 1831

Definitions

- HALIAEETUS

- albicilla / albicillus

- groenlandica / groenlandicus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Haliaeetus albicilla albicilla Scientific name definitions

Systematics History

Haliaëtos Groenlandicus Brehm, 1831, Handbuch der Naturgeschichte aller Vögel Deutschlands, p. 16. Type locality given as Greenland (32).

Distribution

Western Greenland.

Identification Summary

Similar to nominate albicilla, but larger on average (1).

Haliaeetus albicilla albicilla (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- HALIAEETUS

- albicilla / albicillus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Distribution

Southwestern Greenland; western Iceland; northern and central Eurasia south to Greece and Turkey, southern Caspian Sea, Lake Balkhash, and northeastern China; formerly to lower Yangtze River and very likely Egypt (33); has bred on Attu Island (western Aleutian Islands, Alaska). Winters south to northern Mediterranean, Israel, Persian Gulf, Pakistan, northern India, northern Myanmar, and southeastern China.

Habitat

Diverse aquatic habitats, both freshwater and marine: coasts, rocky islands, lakes, large rivers and large marshes. From desert to Arctic biomes. For nesting and roosting requires proximity to sea cliffs or forests, the latter ideally with tall trees. Rarely far from coast or large stretches of water; normally in lowlands (1, 34). Frequents commercial fish farms and carp ponds in some areas (1).

Movement

Mainly migratory in north and east of breeding range; sedentary elsewhere, including Greenland, Iceland, and Norway. Juveniles more dispersive and gregarious; in winter can form flocks of tens of birds (even 100) in good feeding or roosting areas (e.g., 72 on Hortobagy Plain, Hungary, in December 1993). In winter, straggles south from southern Sweden through central Europe, rarely to southern Europe; in Asia, movements poorly known, with birds occurring from Middle East to eastern China and Japan . Adults leave northern breeding areas later (October) and return earlier (February–April) than juveniles. Two adults fitted with satellite transmitters during winter on Hokkaido, Japan, departed for the breeding grounds on the Kamchatka Peninsula in late February, moving north along the west coast of Asia; they began southward migration from 10–12 October, flying south down the Kamchatka Peninsula and then crossing the Sea of Okhotsk to Hokkaido (35). An adult female fitted with a GPS datalogger in Germany had a home range of 8.22 km2 (minimum convex polygon method) from July to January (36).

Diet and Foraging

Wide range of food types, including fish , birds and, less often, mammals; prey normally medium-sized. Fish probably main prey in many areas; some taken dead or dying, others normally caught without plunge ; species that swim near surface most important, e.g., lumpsucker (Cyclopterus lumpus) and Gadidae at sea, and pike (Esox lucius) in fresh water. Avian prey mainly seabirds and waterbirds, particularly species that dive, which are attacked on water (37), sometimes being chased to exhaustion by pair of eagles; also catches ducks in flight (38). During breeding often steals chicks and sometimes eggs from colonies, particularly of eiders and other Anatidae, auks, shags, gulls, and coots. Mammals include rodents, rabbits and hares, and ungulates (sheep, goats and deer); almost exclusively taken as carrion, although young individuals sometimes hunted. Also steals from birds, e.g. Osprey (Pandion haliaetus), other birds of prey, and cormorants. Has learned to take offal from fishing boats and exploits easy fishing in fish breeding ponds. Data on seasonal diet composition and food availability of seven territorial pairs in northeastern Germany, combined with analyses of stomach contents of 126 individuals found dead during 1996–2008 throughout Germany, revealed fish as primary prey, and waterfowl and carcasses of game mammals comprising large part of alternative dietary components: the eagles used individual foraging tactics (adjusted to local food supply) to maximize profitability and, when fish availability declined sharply, they switched to waterfowl and carrion, with consumption of game-mammal carrion increasing in autumn and winter (39). Recent suggestions that reintroduced population in Scotland have adverse effects on resident Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) population appears unfounded: present species took more sheep and aquatic/coastal food items, whereas Golden Eagle fed more on galliforms, lagomorphs, and other terrestrial prey; no evidence that it had any long-term effect on breeding productivity or abundance of latter (40).

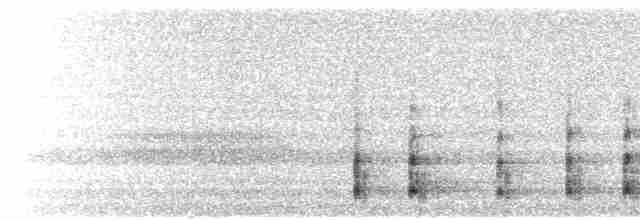

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Mainly vocal during breeding season, a series of piercing yelps, "kyo-kyo-klee-klee-klee-klee...," to which the bird’s partner often responds immediately with a similar series. Also single yelps, “kleee” or a gull-like “kyueew,” in a variety of contexts.

Breeding

Laying dates vary considerably with latitude: January in south of range; April–May in Arctic regions. Nests mainly on ledges of sea cliffs or on high trees , rarely on ground ; tree nest placed in fork or touching trunk. Each pair normally has 2–3 nests, which are used alternately; enormous structures of sticks and branches, which in time can become several meters deep and wide; cup lined with materials such as moss, grass, lichens, ferns, seaweed, or wool. Twelve tree nests in Kazakhstan averaged 107 cm × 148 cm across and 13.2 m above ground (41); 10 tree nests in Czech Republic ranged from 18–35 m above ground (42). Usually 2 eggs (1–3), laid at interval of 2–4 d; average dimensions 74.7 mm × 57.1 mm (33); incubation 38 d (perhaps 34–46) per egg, starting with first egg; adults share incubation and care of young; chicks have first down gray, second down gray-brown; fledging 70–90 d; young depend on adults at least 30 d more. Breeding failure can be very high; 1–2 (very occasionally 3) chicks fledge, with averages of 0.2–1.1 per breeding pair and 1.1–2.0 per successful pair; 13 young fledged from 12 nesting attempts in Czech Republic in 1998 and 1999 (42). Low juvenile mortality. Sexual maturity at 5 years old, maybe younger. Can live to 27 years old (42 in captivity).

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). Previously considered Vulnerable. CITES I. Marked decline historically from 1800s, with drastic reduction and extinction from extensive areas, including British Isles, Faeroes, western Europe, and most of Mediterranean. Trend reversed, with recolonizations in different periods of 1900s, becoming generalized from 1980s. In Lithuania, for example, population recovered from 0 to 120 pairs between 1985 and 2011 (43). By early 1990s, species was increasing in most of Europe and stable or with slight increase in former USSR, but in decline and seriously threatened in southeastern Europe. Total numbers not accurately known, depending considerably on estimates from former USSR, with largest population of possibly 5,000–7,000 pairs. Figures available for early 1990s include: ca. 1,500 pairs in Norway; 1,000 pairs in European Russia, where greatest density on lower Volga, with 250–300 pairs; 245+ pairs in Poland; ca. 200 pairs in Germany; ca. 100 pairs in Sweden; 80 pairs in Finland; 50–90 pairs in Byelorussia; and 50–60 pairs in Baltic republics. In 2015, BirdLife International estimated that 9,000–12,300 pairs nested in Europe, including 150–200 in Greenland, 220–250 in Estonia, 226–271 in Hungary, 450 in Finland, 628–643 in Germany, 550–700 in Sweden, 1,000–1,400 in Poland, 2,000–3,000 in Russia, and 2,800–4,200 in Norway. Asian populations little known, with maximum of 20 pairs in Japan, and maybe 15–25 pairs in Turkey (1980s). Main causes of decline were direct persecution, use of poisoned baits and habitat destruction, especially drainage and forestry; from mid-1900s century, seriously affected by pollution with organochlorine pesticides and heavy metals, particularly in Baltic, with significant reduction in breeding success. In German study, autumn and winter increase in consumption of game-mammal carrion positively correlated with seasonal increase in incidence of lead poisoning throughout the country (stomachs of lead-poisoned eagles contained predominantly ungulate remains); results indicate that carcasses of game mammals were major sources of lead fragments, and link between feeding ecology and lead poisoning is the response of raptors to changing food supply or poor habitat quality, leading to scavenging on lead-contaminated carrion (39). Recovery has been based on active protection, including guarding of nests and supply of uncontaminated food in winter; also favored by drop in levels of some toxins. Threats continue to varying degrees, and habitat is subject to tourist development and privatization of land for development. On the basis of a 10-year dataset on reproductive success at 47 nests before and after presence of a windfarm in western Norway, nests within 500 m of turbines experienced a significant decline in reproductive success, mostly owing to territory abandonment but also from nesting adults being killed in collisions with turbines (44). Various reintroduction projects successfully started: first breeding on Rhum (western Scotland) in 1985 and in southern Bohemia in 1986; steady increase in breeding pairs, with 1988 totals of 11 in Scotland and 9 in Czechoslovakia, and chicks have been successfully raised to fledging. By 2005–2010, Scottish population had grown to 37–44 pairs (45).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding