White-winged Redstart Phoenicurus erythrogastrus Scientific name definitions

Text last updated January 12, 2017

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Armenian | Կարմրափորիկ կարմրատուտ |

| Azerbaijani | Qırmızıqarın odquyruq |

| Bulgarian | Кавказка червеноопашка |

| Catalan | cotxa de Güldenstädt |

| Chinese (SIM) | 红腹红尾鸲 |

| Croatian | bjelokapa crvenrepka |

| Czech | rehek bělokřídlý |

| Danish | Bjergrødstjert |

| Dutch | Witkruinroodstaart |

| English | White-winged Redstart |

| English (India) | White-winged Redstart (Güldenstädt's Redstart) |

| English (United States) | White-winged Redstart |

| Finnish | vuorileppälintu |

| French | Rougequeue de Güldenstädt |

| French (France) | Rougequeue de Güldenstädt |

| German | Riesenrotschwanz |

| Greek | Φοινίκουρος του Καυκάσου |

| Hebrew | חכלילית אדומת-בטן |

| Hungarian | Hegyi rozsdafarkú |

| Icelandic | Hlíðaskotta |

| Japanese | シロガシラジョウビタキ |

| Korean | 흰날개딱새 |

| Lithuanian | Ledyninė raudonuodegė |

| Mongolian | Цээжмэг гал сүүлт |

| Norwegian | hvitvingerødstjert |

| Polish | pleszka kaukaska |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Rabirruivo-de-touca-branca |

| Romanian | Codroș caucazian |

| Russian | Краснобрюхая горихвостка |

| Serbian | Crvenotrba crvenrepka |

| Slovak | žltochvost bielohlavý |

| Slovenian | Beloglavi pogorelček |

| Spanish | Colirrojo de Güldenstädt |

| Spanish (Spain) | Colirrojo de Güldenstädt |

| Swedish | bergrödstjärt |

| Turkish | Büyük Kızılkuyruk |

| Ukrainian | Горихвістка червоночерева |

Phoenicurus erythrogastrus (Güldenstädt, 1775)

Definitions

- PHOENICURUS

- phoenicurus

- erythrogaster / erythrogastra / erythrogastrus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

18 cm; 21–29 g. Male nominate race has black face to upper breast, back and wings, white crown and large wing patch, rufous-orange rump and tail, rufous-orange lower breast to undertail-coverts; black bill and legs. Female is plain mid-brown with dull rufous-orange tail (dusky central feathers), slightly buffy wingpanel. Juvenile is brown with buff spotting above, buff with brown mottling below, densest on breast, tail as female; young male has white wing patch. Race <em>grandis</em> is paler.

Systematics History

Editor's Note: This article requires further editing work to merge existing content into the appropriate Subspecies sections. Please bear with us while this update takes place.

Species name is latinized Greek adjective, and must therefore agree. Two subspecies recognized.Subspecies

Phoenicurus erythrogastrus erythrogastrus Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Phoenicurus erythrogastrus erythrogastrus (Güldenstädt, 1775)

Definitions

- PHOENICURUS

- phoenicurus

- erythrogaster / erythrogastra / erythrogastrus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Phoenicurus erythrogastrus grandis Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Phoenicurus erythrogastrus grandis (Gould, 1850)

Definitions

- PHOENICURUS

- phoenicurus

- erythrogaster / erythrogastra / erythrogastrus

- grandis

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

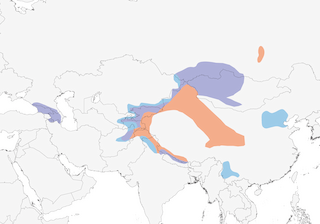

Distribution

Editor's Note: Additional distribution information for this taxon can be found in the 'Subspecies' article above. In the future we will develop a range-wide distribution article.

Habitat

Breeds in alpine zone (above upper tree-line and dwarf-scrub zone) near permanent snows, in dry streambeds, boulder-strewn alpine meadows, stonefields and screes with some trees and herbs, flat parts of high passes, mountain gorges, at 3600–5200 m, occasionally to 5500 m, but mainly (Himalayas) 3900–4800 m; requires combination of rugged rocky terrain and patches of cold-tolerant vegetation. Winters in rocky, scrubby hillsides near streams and riverbeds, rocky moraines, and thickets in valley bottoms, at 1500–4800 m, with great partiality to Hippophae thickets.

Movement

Much of Caucasus population winters in upper R Terek basin, but timing and distance travelled vary with age, possibly sex, and weather: juveniles descend first, Sept in highest areas, Oct–Nov elsewhere, some adults not descending until mid-Dec; return in Mar. Some vertical movements in Himalayas, where some travel farther, perhaps in nomadic fashion; in Ladakh (where a scarce breeder) movements of migrants, possibly originating in Tibet, begin mid-Sept, numbers building steadily to peak passage towards end Oct, and still considerable in early Nov. In Pakistan and China males recorded as remaining at upper elevations, while females descend lower. Russian montane birds descend mid-Sept to mid-Oct and ascend Apr to early May. A summer visitor in EC Afghanistan. Populations in NE part of range to Baikal basin also fully migratory, apparently moving long distance S to NE China.

Diet and Foraging

In summer exclusively invertebrates, mostly insects (in particular moths) and spiders; berries prime and perhaps usually sole food in winter, in particular those of sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides), but midges also seen to be taken near water in Jan–Feb. Invertebrate food includes adult and larval beetles of at least seven families, grasshoppers, bush-crickets, bugs, adult and larval lepidopterans, adult and larval flies, ants, ichneumon flies, spiders, centipedes and earthworms; plant food (other than Hippophae) includes fruits and seeds of juniper (Juniperus), docks and knotweed (Polygonaceae), buttercups (Ranunculus), barberry (Berberis), joint pine (Ephedra), legumes, sedges, grasses and leaves. Stomachs of birds from C Asia, spring to autumn, commonly held beetles, but often also small seeds and leaves; chironomid midges appear important in Caucasus region in Jan–Feb, although winter diet mainly fruit. Forages in short flights from perch ; more “nomadic” than congeners, continually moving on to new perch, rather than returning to well-established one, and perhaps more frequently aerial; also sometimes scavenges from dead animals. In one set of observations berries were taken from ground, rather than on bush. Males wintering at high elevations sometimes feed in snow.

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Song , from prominent perch or in display-flight, a series of short clear melancholy whistled phrases mixed with variety of quiet chirps, clicks and twitters, interspersed with mimicry: a rapid whistled “tit-tit-titer” followed by wheezy burst of short notes, very like song of P. ochruros. Calls include “drrrrt” in intraspecific aggression, weak “lik” or “tsee” in contact, harder “tek” or “tak-tak-tak” in mild agitation, last two combined to loud “tseee-tek-tek” frequently repeated in agitation near nest.

Breeding

Jun–Jul in Caucasus and C Asia. Nest a bulky cup of grass and wool, lined with animal hair and feathers, placed well inside crevice in cliff or deep under rocks, amid screes and often adjacent to moraine sediment, often near permanent snow-line. Eggs 3–5, blue (nominate) or white (race grandis) with reddish speckles; incubation period 12–16 days; nestling period 14 days (two studies) or 21–22 days (two studies); post-fledging dependence at least 7 days.

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened. In 2000, European population (Caucasus) estimated at 1200–6000 pairs, and generally stable. Common in Caucasus and C Asia; casual in Armenia. Locally common in N Pakistan; fairly common in China. Breeding densities generally fairly low, e.g. three pairs in 3 km² and one pair in 4 km² in Caucasus, rising to eight pairs in 2·5 km² in one area of Russia, and in Pamirs pairs typically 900–1000 m apart. Key threat in Caucasus is recent reduction in quantity and range of Hippophae rhamnoides owing to building development; in Caucasus winter densities of 3·8 birds/ha recorded in Hippophae thickets; conservation of stands of this plant is urgent in upper Terek basin. Similar considerations may apply in other parts of species’ range, since evidently Hippophae has remarkable capacity to draw concentrations of this species from very wide areas. In one area of Hippophae covering 0·6 ha in Ladakh, as many as 25 individuals were present.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding