Sooty Shearwater Ardenna grisea Scientific name definitions

- NT Near Threatened

- Names (57)

- Monotypic

Text last updated March 21, 2017

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Malbaartjie |

| Arabic | جلم ماء فاحم |

| Asturian | Pardiella escura |

| Basque | Gabai iluna |

| Bulgarian | Сив буревестник |

| Catalan | baldriga grisa |

| Chinese | 灰水薙鳥 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 灰鹱 |

| Croatian | mrki zovoj |

| Czech | buřňák temný |

| Danish | Sodfarvet Skråpe |

| Dutch | Grauwe Pijlstormvogel |

| English | Sooty Shearwater |

| English (United States) | Sooty Shearwater |

| Faroese | Gráskrápur |

| Finnish | nokiliitäjä |

| French | Puffin fuligineux |

| French (France) | Puffin fuligineux |

| Galician | Pardela escura |

| German | Dunkelsturmtaucher |

| Greek | Αιθαλόμυχος |

| Hebrew | יסעור כהה |

| Hungarian | Szürke vészmadár |

| Icelandic | Gráskrofa |

| Indonesian | Penggunting-laut kelam |

| Italian | Berta grigia |

| Japanese | ハイイロミズナギドリ |

| Korean | 사대양슴새 |

| Latvian | Tumšais vētrasputns |

| Lithuanian | Pilkoji audronaša |

| Norwegian | grålire |

| Persian | کبوتر دریایی دودی |

| Polish | burzyk szary |

| Portuguese (Angola) | Pardela-preta |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | pardela-escura |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Pardela-preta |

| Romanian | Ielcovan brun |

| Russian | Серый буревестник |

| Serbian | Čađavi zovoj |

| Slovak | víchrovník tmavý |

| Slovenian | Črni viharnik |

| Spanish | Pardela Sombría |

| Spanish (Argentina) | Pardela Oscura |

| Spanish (Chile) | Fardela negra |

| Spanish (Costa Rica) | Pardela Sombría |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Pampero oscuro |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Pardela Sombría |

| Spanish (Honduras) | Pardela Sombría |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Pardela Gris |

| Spanish (Panama) | Pardela Sombría |

| Spanish (Peru) | Pardela Oscura |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Pampero Cenizo |

| Spanish (Spain) | Pardela sombría |

| Spanish (Uruguay) | Pardela Oscura |

| Swedish | grålira |

| Turkish | Külrengi Yelkovan |

| Ukrainian | Буревісник сивий |

Ardenna grisea (Gmelin, 1789)

Definitions

- ARDENNA

- grisea

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

The Sooty Shearwater is one of the most common seabirds in the world and easily the most common member of its genus. They breed in enormous colonies in both the south Pacific and Atlantic Oceans on islands off southeast Australia, New Zealand and Tierra del Fuego (South America) where certain breeding congregations can exceed 2.5 million pairs. When not breeding the Sooty Shearwater embarks upon one of largest mass migrations known. Shortly after fledging the population begins to move towards the northwest corner of their respective oceans and following the prevailing winds, eventually move to the east arriving in western North America and Europe late in the local summer. From there they move south back to their breeding grounds. The species is also the only shearwater that can be legally harvested in New Zealand, with the native Maoris taking up to 250,000 chicks for food, soap and oil.

Field Identification

40–51 cm; 650–978 g; wingspan 94–109 cm. Largish dark shearwater with relatively narrow, pointed wings, and pale areas on central underwing . Most of plumage rather uniform sooty-brown to dark greyish , usually darkest on head and on upper surface of primaries and tail, dorsal area may have scaly pattern, especially on scapulars; chin and upper throat slightly paler, rest of underparts from upper chest similar to upperparts but slightly paler; axillaries dark, underwing-coverts paler brownish or grey, with variable amount of white on innermost greater coverts, median and lesser coverts, often whitest on lesser and especially median primary-coverts, many usually with narrow dark shaft-streaks, remiges dark greyish, slightly and diffusely paler at primary bases; iris blackish brown; bill brownish grey to dark grey, sometimes blacker at tip; legs and feet pale flesh, dull pink-flesh or greyish, the outer side of tarsus and outer toe often tinged dusky. Sexes alike. Juvenile as adult, but is in fresh plumage May–Jul when most older birds are in wing moult (1). Most similar to A. tenuirostris but usually has less rounded head with longer bill , usually only slight or no contrast between cap and throat, underwing has large whitish area on carpal contrasting with dark greater primary-coverts and bases of primaries, while in profile at very close range the bill tends to form three broadly equal parts (maxillary unguis, culminicorn and nostril tube), whereas in A. grisea the culminicorn appears longer than the other two parts, although it is unclear how useful this feature might be. From Puffinus mauretanicus and other similar smallish shearwaters by larger size, heavier body, long narrow pointed wings, and plainer dark abdominal area; whitish on underwing prevents confusion with other dark shearwaters, bill colour and proportions additionally assist versus A. carneipes, while long slender bill with no white at its base useful versus some dark Pterodroma.

Systematics History

Subspecies

Distribution

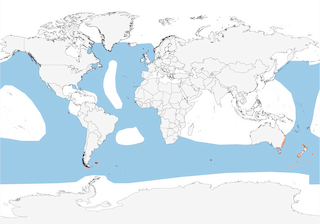

All major oceans except N Indian Ocean, breeding in S Chile and Falkland Is, in Tristan da Cunha (2), and in SE Australia and New Zealand area.

Habitat

Marine ; generally occurs in cold offshore and pelagic waters; satellite-tracking studies in US waters (i.e. during the non-breeding period) over two different years found that the species spent 68% and 46% of time over continental shelf (< 200 m) waters, 27% and 43% of time over the slope (200–1000 m), and 5% and 11% of time over continental rise and abyssal regions (>1000 m), respectively (3). Breeds on slopes, often covered with dense vegetation , usually Poa tussock but also Olearia forest (4), mainly near sea but also inland, up to 1500 m above sea-level, typically on islands but also mainland headlands (4).

Movement

Transequatorial migrant, moving into N Pacific (where more abundant) and N Atlantic ; non-breeders depart first, followed by breeders in mid Apr and fledglings on average c. 1 month later (4). Migratory pathways are generally poorly known, although in Pacific there are records from Papua New Guinea (5), New Caledonia (6), Tonga, Samoa, Fiji, Kiribati, Cook Is, Society Is and Marquesas (7, 8). Large numbers first head into NW sector of respective ocean, arriving late Apr/early Jun, then progressively move E following prevailing winds to reach W coasts of North America and Europe late in local summer, with return migration commencing in late Aug and completed by early Dec (4); many thus complete wide loop before returning to breeding islands; however, non-breeders were suspected (9) (and have been recently confirmed through satellite-tagging) (10) to perform figure-of-eight loop totalling 64,000 km over the Pacific, E to the Peru Current (Jan–Apr?), NW to N Pacific (Mar–May), then E to California Current (May–Oct, though present from Mar and peak numbers only until Aug, with juveniles arriving from Jun), and finally SW through C Pacific back to New Zealand (Aug–Dec) (1), covering up to 910 km/day (10), whereas breeders cover c. 29,000 km (4). In Pacific, particularly large concentrations have been observed E of Japan, off Kurils (May–Oct) and Gulf of Alaska region (1), as well as within 100 km of California, in Monterey Bay (> 5,000,000 birds, at least formerly; see Status and Conservation), but also in Hecate Strait, British Columbia (4, 1). Occasionally recorded inland in SW USA (especially at Salton Sea) and off W North America small numbers remain beyond Nov, even throughout boreal winter, sometimes as far N as British Columbia; generally uncommon to rare further S, off Middle America, at any season, mainly Mar/Apr and Sept/Oct (1). Most South American birds may move fairly directly up and down W coasts of Americas, perhaps especially during years of poor productivity in Humboldt Current (1), although large numbers have been observed only as far N as C Chile in Jun (4) and at least some obviously move N in Atlantic, reaching E North America (N as far as SE Baffin I and SW Greenland) by Apr (mainly present Jun–Sept), thereafter mainly moving E across N Atlantic in Jul–Sept (where concentrations noted over Rockall Bank and around Faeroes, and recorded as far N as Bear I) (11), before moving S again (4), with signficant passage recently recorded off Gabon in Oct (12) (occasionally entering Baltic with records as far as Poland, Finland and Latvia, penetrates Mediterranean as far as Israel, and recorded well inland, for example in Switzerland) (11, 13, 14), although some appear not to cross Atlantic, instead remaining off NE North America until about Nov, much more rarely Dec (exceptionally Jan–Apr), and only very occasionally enters Caribbean or Gulf of Mexico (15, 16) (although records there are year-round), with exceptional inland records in USA (as far as Alabama) (1). Records in the W Mediterranean have sharply increased during the last decades, being mostly in spring (40% in Mar–May) (17). In E Atlantic recorded as late as Jan in Gulf of Guinea (18). Some birds remain in Southern Ocean over winter, for example off New Zealand (19) and in South African waters, especially off S & W coasts, where the species is also present at other seasons (presumably non- or failed breeders), but perhaps also pre-breeders from New Zealand colonies (20). Generally reported not to move N in Indian Ocean, but recorded in Gulf of Eilat in spring and summer (though overland passage between Mediterranean and Red Sea is known) (21, 22) and is vagrant off Oman (eight records, Apr–Oct) (23), Iran (Jun 2008) (24), United Arab Emirates (eight records, all since 1995) (25) and to Kenya (May 2004) (26), with two undocumented records from Sri Lanka often regarded as referring to another species (27). During breeding season, New Zealand breeders feed over S Pacific and Tasman Sea, but also travel S to Antarctic pack ice (4). Recent satellite tracking efforts during this period has revealed the extraordinary dispersal abilities of this species: during pre-laying exodus, one male flew a minimum of 7700 km over 34 days, another flew 4200 km during 28 days and the minimum distance covered by a female was 3700 km during 16 days; pre-breeders mainly frequented waters < 1000 m deep, and during the mid-breeding period a male flew a minimum of 18,000 km in 36 days, while the female flew 4100 km in 13 days (28).

Diet and Foraging

Mainly small shoaling fish, cephalopods (Onychoteuthis, Gonatus, Loligo opalescens) and crustaceans, proportions varying with season and locality, although most available data are from non-breeding season (4); fish include anchovies (Engraulis), spawning capelin (Mallotus villosus), young of Helecolenus/Neosebastes and Cololabis saire. During breeding season, diet apparently dominated by euphausiid crustacea, especially Nyctiphanes australis, and myctophid fish, with the former caught during short foraging trips and the latter on longer trips during chick-rearing period (4), while other foods at this period include arrow squid (Nototodarus sp.) and amphipods (Hyperiella antarctica) (29). Feeds mainly by pursuit-plunging and diving from heights of 3–5 m and regularly reaching 30–40 m below surface (exceptionally 67 m) (30), sometimes also by surface-seizing and hydroplaning. Frequently associates in large numbers with other seabirds, especially other Procellariiformes, penguins, gulls, cormorants (e.g. Imperial Shag Phalacrocorax atriceps) (31), pelicans (1) and terns, as well as sometimes with cetaceans (6). Birds sometimes attend trawlers in large numbers (> 2000 birds) (19), probably mostly juveniles.

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Noisy at colonies, but probably mostly silent at sea (6). Mostly vocalizes on ground or from burrow, but only comparatively rarely in flight, with the main call, a repeated eerie cat-like howling “wheeoohar”, hoarse moaning “der-rer-ah” or a higher-pitched “coo-roo-ah”, made partly through inhalation and partially by exhalation; male calls are perhaps higher-pitched, while in courtship pairs duet (4).

Breeding

Starts late Sept/early Oct with return to colony, followed by pre-laying exodus of c. 14 days, egg-laying from mid Nov to early Dec in New Zealand (with little inter-annual variation, and two-thirds of eggs laid 20–24 Nov on Snares), hatching from mid Jan and fledging in late Apr/early May (4). Monogamous, although pair-bonds are suspected to survive just one season; defends burrow entrance (6). Highly colonial , at densities of up to 1·9 burrows/m² in Poa tussock and 1·2/m² in Olearia forest (4), but more typically 0·3–0·9 burrows/m² (32), sharing breeding grounds with White-faced Storm-petrels (Pelagodroma marina), Pachyptila vittata, Common Diving-petrels (Pelecanoides urinatrix), Grey-backed Storm-petrels (Garrodia nereis) and Pterodroma axillaris on South East I (Chathams) (33); nests in self-excavated burrows up to 3 m long (4), with sparse lining, sometimes in cavities, and can be out-competed for nest-sites by Snares Penguins (Eudyptes robustus) on archipelago of same name (6). Single white egg , mean size 77·4 mm × 48·3 mm, mass 95 g (4); incubation 53–56 days, with stints of 4–9 days; chicks have smoky grey down with paler underparts, brooded for 2–5 days and then fed on average every 0·35 days, the adults alternating between short (1–3 day) and long (5–15 day) trips, delivering mean meals of 96 g and 193 g, respectively (4); fledging 86–106 (mean 97) days at mean weight of 746 g, while it has been suggested that peak mass is achieved around 70 days (4). Mass at fledging appears to influence future survival prospects: of fledglings with a mass in range 564–900 g, 5·4% were recaptured compared to 13 of fledglings in the range 901–1415 g (34). Sexual maturity probably at 5–9 years, although first return to colonies is any time between age two and ten years (mean 4·8 years), while mean age of first breeding has been calculated at 7·7 years (35). Estimates of annual survival prior to two years old 0·54 at Taiaroa Head, South I, and 0·41 at the Snares during same study (35). Adult survival c. 93% (4).

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened. Currently considered Near Threatened. Abundant and widespread, with total population of several million birds, including perhaps 4,000,000 pairs in New Zealand alone and 20,000,000 birds in total, although there is evidence for a decline over past c. 3 decades (4). Probably 2,750,000 breeding pairs on Snares Is (1970/71), but 2,060,000 pairs in 1996–2000, a decline of c. 37%, while other colonies in New Zealand region are also decreasing (as partially indicated by beached bird surveys) (36) or have not responded to predator control (4); has been suggested that at least some mainland colonies are no longer extant (37). Elsewhere, colonies on 17 Australian islands all small (< 1000 pairs) and totalling just 1300–3500 pairs (38), with c. 10,000–20,000 pairs in the Falklands (39), but many more in S Chile, where some colonies are estimated to number up to 200,000 pairs (4) and recently confirmed to breed on Tristan da Cunha, with breeding also suspected on Inaccessible I (6). Numbers present in California Current during non-breeding season have declined by 90% over the past 20 years (40), with for example daily counts in 1970s of up to 10,000 declining to just c. 10 birds in 1990s, although it has been suggested that numbers have shifted to W & C Pacific tracking cooler waters (4, 1). Only petrel species that can legally be sold in New Zealand area; important commercial exploitation, with up to 250,000 young taken yearly by local Maoris (who typically select larger and better-developed chicks) (41), mostly for food but also for soap and oil. Recent research has focused on whether this harvesting is truly sustainable as long assumed (42). Some predation by alien fauna, including cats, rats, pigs and Wekas (Gallirallus australis) (43); natural predators have included Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus) (44). Several thousand birds drown in gill nets in N Pacific each year and driftnets were formerly estimated to take 350,000 birds annually (4). Elimination of introduced predators from breeding islands recommended, but it has been suggested that recent declines are associated with climate change (4) and especially fisheries bycatch (45) with, for example, total of 98% of 1231 dead procellarids recovered as bycatch and examined by researchers in New Zealand waters being this species (46). A mass mortality event was recorded in the coast of C Peru in 2010 (47).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding