Common Pochard Aythya ferina Scientific name definitions

- VU Vulnerable

- Names (52)

- Monotypic

Text last updated May 26, 2016

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Albanian | Kryekuqe e mjeme |

| Arabic | بطة حمراء الراس |

| Armenian | Կարմրագլուխ սուզաբադ |

| Assamese | ডুবডুবি হাঁহ |

| Asturian | Parru europñu |

| Azerbaijani | Qırmızıbaş dalğıc |

| Basque | Murgilari arrunta |

| Bulgarian | Кафявоглава потапница |

| Catalan | morell cap-roig |

| Chinese | 紅頭潛鴨 |

| Chinese (Hong Kong SAR China) | 紅頭潛鴨 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 红头潜鸭 |

| Croatian | glavata patka |

| Czech | polák velký |

| Danish | Taffeland |

| Dutch | Tafeleend |

| English | Common Pochard |

| English (United States) | Common Pochard |

| Faroese | Høvuðreyð ont |

| Finnish | punasotka |

| French | Fuligule milouin |

| French (France) | Fuligule milouin |

| Galician | Pato chupón europeo |

| German | Tafelente |

| Greek | Γκισάρι |

| Hebrew | צולל חלודי |

| Hungarian | Barátréce |

| Icelandic | Skutulönd |

| Italian | Moriglione |

| Japanese | ホシハジロ |

| Korean | 흰죽지 |

| Latvian | Brūnkaklis |

| Lithuanian | Rudagalvė antis |

| Malayalam | ചെന്തലയൻ എരണ്ട |

| Marathi | छोटी लालसरी |

| Mongolian | Улаан хүзүүт шумбуур |

| Norwegian | taffeland |

| Persian | اردک سرحنایی |

| Polish | głowienka |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Zarro |

| Romanian | Rață cu cap castaniu |

| Russian | Красноголовый нырок |

| Serbian | Riđoglava patka |

| Slovak | chochlačka sivá |

| Slovenian | Sivka |

| Spanish | Porrón Europeo |

| Spanish (Costa Rica) | Porrón Europeo |

| Spanish (Spain) | Porrón europeo |

| Swedish | brunand |

| Thai | เป็ดโปช้าดหลังขาว |

| Turkish | Elmabaş Patka |

| Ukrainian | Попелюх звичайний |

Aythya ferina (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- AYTHYA

- ferina

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

42–49 cm (1); male 585–1240 g, female 467–1090 g (2); wingspan 72–82 cm (1). Breeding male has rufous-chestnut head , blackish breast, upper mantle, undertail-coverts, rump and tail, body grey with vermiculations , becoming darker on upperwing-coverts, paler and more uniform silver-grey on flight feathers, with darker tips to primaries and secondaries, and almost white underwing ; bill usually dark grey with black nail and broad, pale grey subterminal band; legs and feet bluish grey, and bright orange-red eyes . Female-like eclipse plumage, but always has greyer body than latter, more contrasting dark breast and no well-defined facial pattern. Female has dull brown head with pale grey eyestripe, throat, lores and cheeks (pattern very variable), greyish-brown body , becoming darker above, wings as male but overall browner; bill dull grey to blackish, with broad black tip and broad, pale grey subterminal band, and eyes warm brown. Very similar to allopatric A. americana but head shape different: male has red iris (yellow in A. americana) and slightly different pattern on bill ; female has different bill colour and whiter flanks than A. americana. Male A. valisineria is larger and overall paler than male of present species, and has blackish wash to head, flatter forehead and much longer, all-dark bill, although note that some of present species can have an all-blackish bill (like A. valisineria) or a narrow, pale, subterminal band and black tip (as in A. americana (3) and some A. fuligula × A. ferina hybrids) (4). Care is also required when faced with potential vagrants of any of these species in also eliminating potential hybrids, which are comparatively frequent (5). Juvenile resembles adult female but has more mottled underparts, duller head lacking eyestripe, has pale grey or white vermiculations on some body feathers, and mantle, breast and flanks are dark grey; appears to take more than one year to achieve full adult plumage; young female distinguished from male by having uniform grey-brown mantle, scapulars and tertials with olive fringes, brown-grey wing-coverts and unflecked white tips to secondaries (2).

Systematics History

Subspecies

Hybridization

Hybrid Records and Media Contributed to eBird

-

Mallard x Common Pochard (hybrid) Anas platyrhynchos x Aythya ferina

-

Red-crested x Common Pochard (hybrid) Netta rufina x Aythya ferina

-

Common Pochard x Ferruginous Duck (hybrid) Aythya ferina x nyroca

-

Common x Baer's Pochard (hybrid) Aythya ferina x baeri

-

Common Pochard x Tufted Duck (hybrid) Aythya ferina x fuligula

Distribution

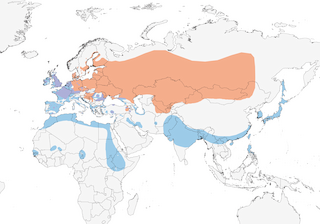

Breeds in W Europe E through C Asia (in band at 40–60° N) to SC Siberia and N China to 120° E. Winters S to N & E Africa, India and S & E Asia.

Habitat

Well-vegetated eutropic to neutral swamps, marshes, lakes and slow-flowing rivers with areas of open water and abundant emergent fringing vegetation (2), but also breeds on saline, brackish and soda lakes, occasionally even in sheltered coastal bays (2). In winter, often on larger lakes, reservoirs, fishponds, mineral extraction pits, brackish coastal lagoons and tidal estuaries, but ranging from oliogotrophic upland waterbodies to lowland eutrophic lakes (2). Recorded to 2690 m in Ethiopia in winter (7).

Movement

Partially migratory, but some individuals may migrate very long distances, with up to 1000 km sometimes covered in just 2–3 days (8), thus although most British-ringed birds originate from Baltic states, Russia, Germany and Finland, there are recoveries during the breeding season as far as 150º E; neverthless, most far eastern breeders doubtless winter in SE & E Asia (2). Birds ringed or recovered in Switzerland have been recovered (or ringed) in S France, C & E Europe and E to lowland W Siberia, and during the breeding season recoveries concentrate in the Russian-Kazakh steppe, while in winter movements regularly occur between Switzerland and the Po Valley, to S France and in a NW direction (8). Breeders in Denmark, Fennoscandia, N Germany, Poland, Baltic states and Russia between 50º N and 60º N (E to 70º E) move W & SW to W Europe (as far as Ireland) and S to NW Africa, while those wintering in E Mediterranean and Black Sea originate from even further E (1). Males generally depart the breeding areas first (by c. 2 weeks), moving through E & S Europe in late Sept and Oct, and W Europe in Oct–Nov, and females perhaps on average moving further as males quickly populate first suitable waterbodies, while return passage (which has advanced among males by 20 days since 1970s) (8) commences as early as Feb (if weather mild), although most birds leave winter grounds in Mar and early Apr, with males again departing first (1, 8). However, in Ethiopia, present overall between late Oct and early Apr, with occasional records from early May and early Jul (7), whereas in N Kenya the species has been seen in Dec–Mar (9). Present throughout year in temperate regions (e.g. C & NW Europe), where within-winter movements in France can be > 100 km (typically to ice-free areas) (10), but some populations winter in sub-Saharan Africa (exceptionally S to Tanzania, Congo (11, 12), Cameroon, Nigeria (13, 14), Ghana (15) and Gambia) (2), Middle East , SW USSR, Indian Subcontinent, SE Asia and Japan . Vagrant to Faeroes, Azores, Canary and Cape Verde Is; also to Philippines, Mariana Is (Guam and Saipan) (16), Hawaii, Pribilof Is, the W & C Aleutians and mainland Alaska (17), once in Saskatchewan (Jun 1977) (18), in California (Feb 1989, Jan–Feb 1991, Jan–Feb and Nov 1992, Dec 1994) and Quebec (May 2008) (17).

Diet and Foraging

Seeds, roots and green parts of grasses, sedges and aquatic plants (especially Chara, but also Potamogeton, Myriophyllum and Ceratophyllum) (2); also small invertebrates (aquatic insects and their larvae, molluscs, crustaceans, worms), amphibians and small fish; bread (19) and potatoes recorded in some parts of range (20). Perhaps some seasonal or sex-/age-related variation in diet, with females and ducklings apparently reliant on chironomid and caddisfly larvae in summer, and these food sources are also particularly important at sites lacking macrophytes and in other seasons (21, 2). Feeds by diving (usually at depths of 1–2·5 m) (1), upending or dabbling on surface, and also filters mud on shore, but some differences in techniques between males and females, with males apparently deeper divers and dominant in agonistic encounters, sometimes displacing females from food-rich sites (22, 2). Sometimes associated with sewage outfalls in winter, where abundant Tubifex and other species taken (2), and also observed directly associating with, and benefiting from, foraging Cygnus columbianus bewickii, but without kleptoparasitizing the swans (23). Frequently crepuscular and may also feed throughout the night, especially in winter (2). Gathers into large flocks, especially during post-breeding moult, when groups of up to 50,000 males can be common in W Europe and Russia (2).

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Vocalizations generally considered weak, low-pitched and inaudible at any distance (1). Males are generally silent, but utter wheezy whistles in display , e.g. nasal “wiwierr” and louder, single, double-noted or tripled “kil-kil-kil” that descend in pitch (1), while female gives soft growl when flushed and various other, mainly monosyllabic, rasping or explosive calls (1); contact calls of ducklings comprise groups of 2–4 notes, and their distress calls are higher-pitched and faster than those of Anas ducks of same age and size (2).

Breeding

Starts Apr/May, especially latter but depending on region, with breeding grounds in Siberia not usually reached before early May (1); in S Spain, broods observed 22 May to 15 Jun in one study (24) and the season appears similar in East Anglia (SE England) (25). Probably seasonally monogamous, with pair-bond typically surviving until first or second week of incubation, although some males will accompany their broods; pair-bonds usually form in winter, although others not until spring (1). In single pairs or loose groups, sometimes in association with Black-headed Gulls (Larus ridibundus), which apparently offer some measure of protection against predators (26), for example, Hooded Crow (Corvus cornix), Common Raven (C. corax) and American mink (Mustela vison) (27); nest is shallow depression in thick heap of grass, reed stems and leaves, lined with down, on ground or over water, concealed in thick vegetation, usually < 10 m from water (2); in Czech Republic, 77% of 380 nests over water, 16% on islets (elsewhere including man-made ones) (28) and the other 7% on dry ground (2). Generally single-brooded, although up to 45% of birds that lost their first clutches attempted replacements in one study (2). Clutch 8–10 green-grey eggs (range 3–22, with clutch sizes declining later in season, although nests containing > 15 eggs probably result of parasitism), size 56–68 mm × 39–47 mm, mass 55–74 g (2); incubation c. 25 (24–28) (2) days; chicks have brown down on upperparts , and yellow on underparts, face and dorsal spots, becoming white on ventral region, weigh 37·2 on hatching (in captivity) (2); fledging 50–55 days, deserted by female at onset of wing moult, and some young may leave own brood to join other female even when very small (1). Intra- and interspecific parasitism common (up to 89% in one study) (29) and moderate levels of egg dumping appear to have little or no effect on success of host (30), with Netta rufina parasitizing this species in Spain (2), and A. fuligula and Anas platyrhynchos have been recorded dumping eggs in nests of A. ferina in the Czech Republic (29), while both A. ferina and Netta rufina may simultaneously parasitize Anas platyrhynchos in the same country (31). In study of breeding success on Czech fishponds, 66% of females nested successfully, 18% unsuccessfully and remainder did not attempt to breed, with large inter-annual differences reflecting climatic conditions, especially drought, when < 33% of birds attempted to breed (2); water levels also proved to be strong determinant of whether birds decided to breed or not in Swedish study (32). Mean brood size on hatching 7·1 (six in replacement clutches) (2). During a Latvian study, yearling females initiated nests later than older birds, while clutch size and brood size declined seasonally, but there was an age-specific increase in breeding performance between one and two years of age such that brood size and duckling mass of yearling females were smaller than those of older females, thus even inexperienced two year olds nested earlier and produced larger broods and ducklings than younger females (33); also found that site fidelity was positively related to breeding success and that fidelity is higher for older females than young birds (34), while duckling survival and recruitment declined with advancing hatch date (35). Same Latvian study found that natal dispersal among marked birds averaged 629 m ± 39 m (range 0–10·6 km) and was much smaller for breeders at 239 m ± 16 m (range 0–9·2 km) (36). Success of 4·42 young reared to fledging per successful pair, and of 1·83 per pair (all pairs) in one study in Germany; hatching success of 56% found in Czechoslovakia. Sexual maturity at c. 1, occasionally c. 2, years, with a 20-year-old captive bird remaining fertile throughout (2) and no evidence of senescence in wild population (37). Annual adult survival was 65% during a Latvian study (34). Longevity record held by British-ringed bird that was recovered when 22 years old (2).

Conservation Status

VULNERABLE. Abundant, with a global population estimated to number 1,950,000–2,250,000 individuals (38). Westwards spread registered during 19th century when colonized Sweden, Finland, Denmark and the Netherlands, followed by Britain (although some evidence species was breeding there from at least 1840s (39) and where still more numerous in S than N) (40), much of C Europe and France in early 20th century, finally Germany, Belgium (1956) and Spain, this expansion apparently the result of drying of C Asian breeding areas, and facilitated by increasing availability of suitable man-made wetlands and specially provided breeding sites (28), as well as the species’ ability to take advantage of new feeding opportunities (2). First bred in Italy in 1952, Greece (1953, on Crete), Iceland in 1954, Norway in 1972, Morocco in 1977 and Portugal in 1995 (1). European breeding population estimated at 198,000–285,000 pairs (41); largest breeding populations are in European Russia (90,000–120,000 pairs in 2008–2011), Poland (20,000–30,000 pairs in 1992–2004), Ukraine (17,300–25,900 pairs in 2000), Finland (10,000–16,000 pairs in 2006–2012) and Czech Republic (9,000–17,000 pairs in 2012) (41). Wintering population in W Palearctic c. 1,600,000 birds, where now common throughout W Europe (this subpopulation numbers c. 350,000 individuals), and C Europe is a particularly important wintering area, including as a refuge for birds from NW Europe during severe weather there (which has been known to lead to starvation of large numbers of present species) (42, 2). Important numbers also in Asia: over 100,000 winter in Japan; c. 30,000–40,000 in Iran; partial counts in winter 1991 yielded 22,000 in Kazakhstan, 96,300 in Azerbaijan (where up to 75,000 were recorded at Gyzylagach State Reserve in winter in late 1990s) (43), 72,784 in Turkmenistan, 124,694 in Pakistan and 36,212 in India . SW Asian population most recently (late 1990s) estimated at 350,000 birds (trends unknown), with a further 100,000–1,000,000 in S Asia, and perhaps 600,000–1,000,000 in SE & E Asia in 1990s, of which c. 500,000 in China, 30,000 in South Korea and 170,000 in Japan (2) (although numbers there have been in decline since) (44, 45). Wintering population in W Mediterranean has decreased by up to 70% in recent decades, although at least some of these birds have doubtless relocated elsewhere, and signs of decline also evident in E Mediterranean, Black Sea and Sea of Azov regions, which areas together may harbour up to 1,000,000 birds in winter (2). Numbers wintering in the UK have declined c. 50% within the 25 years prior to winter 2010/11 (46) (and the most recent estimates of breeding numbers also indicate a decline there (47), but NW European population as a whole appears to be stable and numbers wintering in the Baltic have decreased only slightly in the last two decades (48). Overall European breeding population estimated to be decreasing by 30–49% over three generations (22·8 years) (41), with European winter population following a similar trend. Since Europe holds 35% of global population (40% in winter), such declines are globally significant BirdLife International (2015) Species factsheet: Aythya ferina. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 19/11/2015. . Furthermore, some Asian populations (in Bangladesh, Japan and South Korea) are reported to be decreasing BirdLife International (2015) Species factsheet: Aythya ferina. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 19/11/2015. . Declines probably due to excessive hunting and habitat destruction and change, with eutrophication an important factor in loss of some suitable habitat; this process promotes development of phytoplankton-dominated wetlands, with opaque rather than clear water, leading to decline in bottom flora, especially Chara, on which this species is so dependent (2). On other hand, species has benefited from waste discharge outfalls from food-processing plants, which provide suitable feeding opportunities (2). Sensitive to disturbance during breeding season (2). Not regarded as a species of conservation concern until 2015, when information suggesting that the population has declined rapidly across the majority of its range caused the species to be classified as Vulnerable.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding