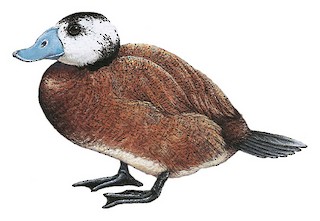

White-headed Duck Oxyura leucocephala Scientific name definitions

- EN Endangered

- Names (43)

- Monotypic

Revision Notes

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Albanian | Rosa kokëbardhë |

| Arabic | بط ابيض الراس |

| Armenian | Սպիտակագլուխ բադ |

| Asturian | Balbasña tiestablanca |

| Azerbaijani | Göydimdik ördək |

| Basque | Ahate buruzuria |

| Bulgarian | Тръноопашата потапница |

| Catalan | malvasia capblanca |

| Chinese (SIM) | 白头硬尾鸭 |

| Croatian | čakora |

| Czech | kachnice bělohlavá |

| Danish | Hvidhovedet Skarveand |

| Dutch | Witkopeend |

| English | White-headed Duck |

| English (United States) | White-headed Duck |

| Finnish | valkopääsorsa |

| French | Érismature à tête blanche |

| French (France) | Érismature à tête blanche |

| Galician | Malvasía de cabeza branca |

| German | Weißkopf-Ruderente |

| Greek | (Ευρωπαϊκό) Κεφαλούδι |

| Hebrew | צחראש לבן |

| Hungarian | Kékcsőrű réce |

| Icelandic | Eirönd |

| Italian | Gobbo rugginoso |

| Japanese | カオジロオタテガモ |

| Latvian | Baltgalvas zilknābis |

| Lithuanian | Baltagalvė stačiauodegė antis |

| Mongolian | Ямаан сүүлт нугас |

| Norwegian | hvithodeand |

| Persian | اردک سرسفید |

| Polish | sterniczka |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Pato-rabo-alçado |

| Romanian | Rață cu cap alb |

| Russian | Савка |

| Serbian | Beloglava plavokljuna patka |

| Slovak | potápnica bielohlavá |

| Slovenian | Beloglavka |

| Spanish | Malvasía Cabeciblanca |

| Spanish (Spain) | Malvasía cabeciblanca |

| Swedish | kopparand |

| Turkish | Dikkuyruk |

| Ukrainian | Савка білоголова |

Revision Notes

Alfredo Salvador, Juan A. Amat, and Andy J. Green revised the account. Peter Pyle contributed to the Plumages, Molts, and Structure page. Eliza Wein generated the map.

Oxyura leucocephala (Scopoli, 1769)

Definitions

- OXYURA

- oxyura

- leucocephala / leucocephalos / leucocephalus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

This species account is dedicated in honor of José Antonio Torres Esquivias, whose efforts made possible the survival of the White-headed Duck in Spain.

“For a moment we return to the white-faced ducks—no European bird-form less known, or more extravagant. With heavy, swollen beaks, quite disproportionate in size and pale waxy-blue in colour, with white heads, black necks, and rich chestnut bodies, their tiny wings (as well as the sheeny silken plumage) recall those of grebes, but they have long stiff tails like cormorants, and are more tenacious of the water than either of those. To push them on wing is well-nigh impossible. They seek safety in the middle waters and there abide, ignoring threats.” Unexplored Spain (1).

The White-headed Duck is a stifftail with a highly fragmented distribution in the central and southwestern Palearctic, from south of Lake Baikal in the east, to northwestern Africa and the Iberian Peninsula in the west. Populations in north-central Asia are migratory, and spend the winter in the Middle East, Türkiye, and southeastern Europe. There are sedentary populations in Spain and northwestern Africa. This charismatic bird is used as a flagship for wetland conservation in several countries in its range, and reintroductions have been attempted in Hungary, Italy, France, and Mallorca Island (Balearic Islands, Spain).

It is a highly aquatic species that is found in a variety of wetlands throughout the year, including natural and man-made habitats, and they exhibit seasonal variations in habitat use. The bulbous base of the bill contains large salt-excreting glands, which are considered an adaptation to brackish and saline habitats. It breeds in a variety of wetlands, including freshwater, brackish, alkaline, and eutrophic lakes with emergent vegetation used for nesting. Wintering sites generally have a larger surface area and lower cover of emergent vegetation compared to breeding sites, and include saline lakes in regions where freshwater ones freeze. The White-headed Duck shows adaptations for diving and the main food sources of adults and immatures are midge larvae (Diptera, Chironomidae) and seeds of aquatic plants.

The mating system of the White-headed Duck is characterized as male-dominance polygyny, in which males compete for females by sorting out positions of dominance. Courtship behaviors are increasingly intense, from relaxed flotilla-swimming to head–high–tail–cock, sideways hunch, kick–flap, and side–ways–piping. During the early breeding season, the males move to open water close to emergent vegetation selected for nesting. In these areas, fighting between males is common and dominance hierarchies are established. First breeding takes place when females are two years old. Females nest over water and their eggs are very large in relation to female size, which may be related to semi-parasitic nesting or to highly precocial ducklings that are tended by the female only for 1–3 weeks.

Considered globally Endangered, it is extinct as a breeder in Europe with the exception of Spain. It has undergone an estimated decline in numbers of 34.4% between 2005 and 2013, and is threatened by competition and hybridization with the introduced Ruddy Duck (Oxyura jamaicensis), habitat alteration, drainage, droughts, and competition with introduced populations of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) and other cyprinids. Other important threats are hunting, ingestion of lead shot, and drowning in fishing–nets.

There are numerous aspects of the natural history of White-headed Duck that are poorly known. The breeding success of males has not been analyzed by means of genetic studies of paternity. Another aspect that remains unstudied is mate selection by females. There are few data about parasitic nesting. Genetic studies of nest maternity would be important to understand nest parasitism. Studies on the effects of both parental and creching behavior on chick survival are needed. Future studies on dispersal and adult survival would be helpful. Migratory routes, stopover sites and destinations are not well-known, and more information is needed. Data on population sizes of this species are inadequate and coordinated censuses are required. The role of White-headed Duck as a dispersal vector for aquatic plants and invertebrates has not been studied.

Knowledge of the White-headed Duck was improved by the work of Amat and Sánchez (2) and the comparative studies of stifftail ducks made in captivity by Montserrat Carbonell (3), largely overlooked until their publication (4).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding