Red Kite Milvus milvus Scientific name definitions

Revision Notes

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Albanian | Huta bishtgërshërë e kuqerreme |

| Arabic | حدأة حمراء |

| Armenian | Կարմիր ցին |

| Asturian | Milñn real |

| Azerbaijani | Qırmızı çalağan |

| Basque | Miru gorria |

| Bulgarian | Червена каня |

| Catalan | milà reial |

| Croatian | crvena lunja |

| Czech | luňák červený |

| Danish | Rød Glente |

| Dutch | Rode Wouw |

| English | Red Kite |

| English (United States) | Red Kite |

| Faroese | Reyðgleða |

| Finnish | isohaarahaukka |

| French | Milan royal |

| French (France) | Milan royal |

| Galician | Miñato real |

| German | Rotmilan |

| Greek | Ψαλιδιάρης |

| Hebrew | דיה אדומה |

| Hungarian | Vörös kánya |

| Icelandic | Svölugleða |

| Italian | Nibbio reale |

| Japanese | アカトビ |

| Latvian | Sarkanā klija |

| Lithuanian | Rudasis peslys |

| Norwegian | rødglente |

| Persian | کورکور حنایی |

| Polish | kania ruda |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Milhafre-real |

| Romanian | Gaie roșie |

| Russian | Красный коршун |

| Serbian | Riđa lunja |

| Slovak | haja červená |

| Slovenian | Rjavi škarnik |

| Spanish | Milano Real |

| Spanish (Spain) | Milano real |

| Swedish | röd glada |

| Turkish | Kızıl Çaylak |

| Ukrainian | Шуліка рудий |

Revision Notes

In this revision, Tim S. David revised the sections that comprise the Systematics page (Geographic Variation, Subspecies, Related Species, Nomenclature, and Fossil History).

Milvus milvus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- MILVUS

- milvus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

The Red Kite (Milvus milvus), with its striking rufous plumage and bold wing pattern occupies a wide variety of open habitats throughout Europe, including open woodlands, pastures, farmland, scrub, and wetlands. It is closely related to the similar Black Kite (Milvus migrans), with which it occasionally hybridizes; the taxonomy between these two species is confused, and requires further study. The species is migratory in the northern portion of its range, with many migrating to southern France and the Iberian Peninsula. They feed on a range of prey items, including small mammals, birds, fish, invertebrates, and carrion, and in some places garbage dumps provide an important source of food. They nest in stick platform nests in trees, where females mostly incubate the eggs and brood and feed the chicks, though the male does most of the hunting. While they are widespread through Europe, there have been severe population declines, especially in the south of its range in Spain and France, but also in Germany and other portions of its range. However, in other areas of its range, it is increasing, such as in Sweden and the United Kingdom, where a reintroduction program was hugely successful.

Field Identification

60–72 cm (1); male 757–1,221 g, female 960–1,600 g (1); wingspan 143–171 cm (1). Larger than Black Kite (Milvus migrans), and redder brown; tail more clearly forked and reddish on top; head whiter ; underwing shows larger, whiter patches on primaries. Juvenile has paler body, darker head, and less rusty colored tail. Subspecies fasciicauda smaller and darker.

Systematics History

Originally described as Falco milvus Linnaeus, 1758 [type locality = "Europe, Asia, Africa"]. The genus Milvus was described by de Lacépède in 1799.

Geographic Variation

Slight geographic variation and much individual variation. A recent genetic study found no significant phylogeographic structure across the European range of this species but an alarmingly low genetic diversity (2).

The most significant geographic form is the much debated Cape Verde Kite (Milvus milvus fasciicauda). This intriguing form used to be found in Northwestern Cape Verde Islands. Its morphology appears to be intermediate between Black Kite (Milvus migrans) and Red Kite, resulting in a form distinctive from both. Some authors have suggested that it could be the result of the hybridization between these two species, while others have hypothesized that this population could belong to an ancestral stock prior to the divergence between Red Kite and Black Kite (1). The relationships of this taxon have been further confused by the misidentification of Black Kites occurring on the same archipelago (but not the same islands) as Cape Verde kites fasciicauda (3, 4, 5). A recent genetic analysis found fasciicauda embedded within milvus (4). Based on this absence of monophyly, the validity of the taxon has been disputed. However, the genetic distance between Milvus taxa is generally small, possibly due to incomplete lineage sorting, while the morphological differences are relatively large (4, 5, 2, 6). On the other hand, some authors have afforded fasciicauda the rank of species in 1990s and 2000s (7, 8). Regardless of its taxonomic status, this form constitutes a challenge to the classification of Milvus kites. Sadly, it has not been recorded in a recent extensive survey and is now probably extinct (9, 4, 5).

Subspecies

Two subspecies tentatively recognized, of which one is probably extinct.

Red Kite (Red) Milvus milvus milvus Scientific name definitions

Systematics History

Falco milvus Linnaeus, 1758. [type locality = "Europe, Asia, Africa"].

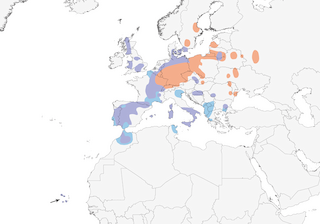

Distribution

Southern Sweden east to Ukraine and southwestern Russia, and south through central Europe to western and central Mediterranean Basin; Britain (Wales, reintroduced Scotland and England); maybe Caucasus; formerly Canary Islands.

Identification Summary

Larger and redder than fasciicauda, with longer, more pointed wings and a longer tail with a deeper fork. More rufous overall, except on the head, which is whitish-gray with dark streaks. There is much individual variation in this subspecies (e.g., in the extent of tail barring). The inner webs of primaries are virtually all-white (pale gray with dark marbling in fasciicauda).

Milvus milvus milvus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- MILVUS

- milvus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Red Kite (Cape Verde) Milvus milvus fasciicauda Scientific name definitions

Systematics History

Milvus milvus fasciicauda Hartert, 1914. [type locality: Santo Antão, Cape Verde].

Distribution

Cape Verde Islands, where almost surely extinct (10).

Identification Summary

Smaller and browner overall than nominate, with shorter, more rounded wings. The tail fork is shallower than in nominate, and the tail somewhat shorter. Less pronounced rufous edgings on upperparts, reddish crown and nape (gray-white in nominate), less rufous underparts, and inner webs of primaries basally pale gray with darker gray marbling (virtually all-white in nominate) (11, 1, 12, 8). In some aspects, this form is somewhat intermediate between Red Kite and Black Kite (Milvus migrans).

Milvus milvus fasciicauda Hartert, 1914

Definitions

- MILVUS

- milvus

- fasciicauda

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Related Species

The Red Kite is sister to the Black Kite (Milvus migrans). The two species are closely related and are not reciprocally monophyletic in some genetic analyses (13, 3, 4). The genus Milvus currently includes two species, but its internal taxonomy is still confused and other species may be recognized in a near future. Milvus kites are closely related to Haliastur kites, but not to the other genera of kites (e.g., Elanus, Ictinia, Harpagus, etc.) (14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19). These two genera are placed by most authors with Haliaeetus (sea-eagles) in the subfamily Haliaeetinae, a group most closely related to hawks of the Buteoninae subfamily (20, 21, 16, 17, 18); these two subfamilies are sometimes combined into a larger and more inclusive Buteoninae (19). Milvine kites (Milvus and Haliastur) and sea-eagles share many morphological and ecological characteristics, notably their affinity to humid areas. They probably split from their closest relatives between 9.8 and 15.7 mya (18).

Milvus milvus and Milvus migrans regularly hybridize in the wild (22, 23).

Nomenclature

The name "Red Kite" refers to the warm colors of this species. It is called Milan royal in French and Milano real in Spanish, which means "Royal Kite" in both cases. The generic and specific name milvus is the Latin word for "kite" (24).

Fossil History

The Red Kite is known from Quaternary deposits of Europe (25).

Distribution

Editor's Note: Additional distribution information for this taxon can be found in the 'Subspecies' article above. In the future we will develop a range-wide distribution article.

Habitat

Open wooded land; varied country, including forests or woods mixed with farmland, pasture, or heathland. Normally at low or medium altitudes, but occurs in woods at up to 2,500 m in Morocco. In winter, tends to occupy more open areas, e.g., farmland without trees, wasteland, scrub, and wetlands; also in winter, roosts in groups of up to 100 or more in clumps of trees, which may be traditional sites, although sedentary adults seem to continue roosting on or near their nests. Historically occurred in cities, e.g., urban scavenger in London (England) in 16th century; still quite closely associated with man, visiting rich feeding areas on edges of towns, e.g., rubbish dumps .

Movement

Mainly migratory in northern and central Europe, although showing an increasing tendency to overwinter in these areas, including southern Sweden, as well as in Switzerland and Germany. Wintering in France was first recorded in 1964 but 5,800 wintered there in 2007 (26). Populations in the south of range and Wales are sedentary, as well as the other increasingly widespread populations in the British Isles, with varying degree of dispersal of juveniles. The vast majority of migrants winter in southern France and especially in the Iberian Peninsula, passing through the western Pyrenean passes, where some 10,000 individuals are recorded on autumn migration (27, 28). Only a few individuals migrate to northern Africa, mainly via Gibraltar (28); however, recorded south even to southern Africa.

Diet and Foraging

Wide range of food types, but essentially carrion and small or medium-sized mammals and birds; diet varies according to local availability, with proportionally more prey captured during breeding. Carrion includes sheep and other livestock, dogs, cats, chickens and their eggs, and all sorts of small animals, including animals knocked down on roads and those wounded by hunters. In Doñana (southern Spain), Graylag Goose (Anser anser) and other Anatidae are important source of carrion owing to their abundance in winter. Mammals hunted include rodents (voles, rats, mice, hamsters, muskrats), insectivores (moles, shrews), lagomorphs (rabbits, hares); birds, especially juveniles, include Corvidae (magpies, jackdaws, crows), Black-headed Gulls (Larus ridibundus) in Wales, and thrushes, larks and starlings. Reptiles, amphibians, and fish generally much less important, as are (at least in terms of weight) invertebrates, e.g. beetles, grasshoppers, and earthworms, which are all taken on the ground, and alate ants, taken on the wing. Forages mainly in open areas, with low flapping or gliding flight, or by diving on to terrestrial prey from higher, soaring flight. Often visits rubbish tips in search of offal and waste from abattoirs; from nest will travel up to 8 km to hunt, and from roost moves much farther afield. GPS tracking in Germany has found home range sizes between 4.8 and 507 km² in successfully breeding males (n = 27) and between 1.1 and 307 km² in successfully breeding females (n = 12); across years, the median home range size of all males ranged between 21 and 186 km² , depending on prey availability, and for individual males at the same nest site, the home range size varied up to a factor of 28 across years; birds with very large home ranges had only one fledgling, which indicates that resources were scarce (29). Some reintroduced birds in England are now being fed deliberately by householders in their gardens (30).

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Often silent away from nest. Commonest call between partners a mewing "weee-oo," not unlike that of Common Buzzard (Buteo buteo) but higher and perhaps shriller; often repeated in short fast series.

Breeding

Laying March–May. Nest a platform of sticks, often with rags or plastic incorporated, and normally lined with wool, built in fork or on wide side branch of tree, coniferous or broadleaf, in forest, wood, or clump of trees; each pair normally has several nests, using same one each year or alternating. Clutch 1–4 eggs, normally 2, sometimes 3, laid at interval of 3 days; replacement laying occurs; incubation essentially by female, starting with first egg, period 31–32 days per egg; female also broods and feeds chicks, though male brings most food; chicks have buff-colored first down, reddish-tinged second down; fledging 50–60 days; chicks fed by adults for at least 2–3 weeks after leaving nest. Success: 1 or 2 chicks fledge, very occasionally 3. First breeding sometimes at 2 years, normally later, up to 7 years. Can live to 26 years (38 years in captivity). Adult survival rate possibly 95% in Wales.

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened. Currently considered Near Threatened. Cape Verde Islands form fasciicauda (quite possibly not even a valid taxon) probably now extinct (5), and all scavenging raptors in that archipelago are under threat owing to poisoning, persecution, and declines in availability of carcasses (31); imminent extinction of all kites in Cape Verdes was evident in 1999, when just two fasciicauda individuals and one Black Kite (Milvus migrans) were found (9).

Nominate subspecies confined as a breeder to western Palearctic. BirdLife puts global population at 21,000–25,500 pairs. European population (95% of breeding range) in first decade of 2000s c. 19,000–23,000 pairs, majority in Germany (10,500–12,500), France (2,300–3,000) and Spain (1,900–2,700), which together hold more than 75% of global population (32). All three main populations declined between 1990 and 2000, during which period the species suffered overall decline of nearly 20%. In Germany, populations in northern foothills of Harz Mountains, the most densely populated part of range, decreased by estimated 50% during 1991–2001. In France, numbers appear stable in southwestern and central parts of country and in Corsica, but have decreased in northeastern region and in northern and eastern Massif Central, with suggested decline of up to 80% in some areas between 1980 and 2000, during which time this kite’s range in France contracted by 15%; national survey in 2008 indicated reduction in breeding numbers of more than 20% over the six years since 2002 (33); January 2007 survey indicated wintering population in France of nearly 6,000 individuals, most in Pyrenees. In Spain, the breeding population fell by 46% from 1994 to 2004, with some indications of recovery since (34, 35). Surveys of wintering birds in Spain in 2004 indicate c. 50% decline since 1994, this downward trend having apparently continued in more recent years (35). The Balearic Islands population, which is resident, fell from 41–47 breeding pairs in 1993 to 27 in 2004, but subsequent conservation measures allowed recovery to 38 pairs in 2007. In rest of range numbers since 1990s appear stable or, as in e.g. United Kingdom, Sweden, Poland, and Switzerland, increasing. For example, Swedish population grew from 30–50 pairs in 1970s to 1,800 pairs in 2007 (32), with rate of increase recorded as 13% annually during 1998–2006, and has been suggested that Sweden’s carrying capacity could be 5,000–10,000 pairs; in Denmark, increased from 17 pairs in 2001 to 81 pairs in 2009. United Kingdom population fell to extreme low during 1900s, when confined to small area of Wales, but combination of conservation action and (from 1989 onwards) a large-scale, widespread, and enormously successful reintroduction project in Scotland and England led to huge increase in recent decades, numbers reaching estimated minimum of 1,600 breeding pairs in 2008 (32) and probably more than 2,200 pairs in 2010 (36); with high breeding success and annual survival, this population still increasing rapidly, and future carrying capacity of United Kingdom estimated at c. 10,000 pairs. In total, population has decreased in recent years following rapid declines of resident breeders in Iberia and in numbers of migrants wintering in Spain. In earlier decades majority of global population wintered in Spain, but increasing numbers now remain on northern European breeding grounds. Populations overwintering outside Spain are, on the whole, increasing and, although significant declines likely to continue in southern Europe and, therefore, in total global population, growth in numbers in northern populations expected ultimately to exceed declines in Iberia.

Perhaps most serious and persistent threat to this species is illegal poisoning (designed to kill predators of livestock and game animals) and indirect poisoning from pesticides, and secondary poisoning through consumption of rodents killed by rodenticides spread on farmland to control voles, especially in wintering ranges in France and Spain; poisoning by pesticides considered primary threat in area of eastern France where bromadiolone widely used to control water voles (Arvicola terrestris) during plagues of latter (37); illegal poisoning and persecution a serious threat also in northern Scotland, where 40% of birds found dead between 1989 and 2006 had been poisoned (38). Reductions in number of grazing livestock, along with intensification of farming leading to chemical pollution, landscape homogenization, and ecological impoverishment, are also threats to the species (32). Proliferation of windfarms a potentially serious hazard, and more research required in order to assess level of threat that these pose; present species a frequent victim at turbines, and recent Swiss study found that growth rates of kite population decreased progressively with increasing number of turbines and that spatial distribution of turbines was critical for survival of populations (39). Electrocution at and collision with powerlines are further threat factors, if less serious, as also are hunting and trapping, egg-collecting, and, at least locally, road traffic, while deforestation can have adverse effects in some places; competition with Black Kite, generally a more successful species, a possible problem in some areas (1), and in Spain and France a reduction in number of open refuse dumps likely to have adverse effect on this and other scavengers. This species is closely monitored in most of its range. Since 2007, following success of the reintroductions in United Kingdom, further such projects have been attempted in two regions of north-central Italy and in Ireland (first recorded breeding attempt in Republic of Ireland in 2009).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding