Cape Griffon Gyps coprotheres Scientific name definitions

- VU Vulnerable

- Names (27)

- Monotypic

Text last updated March 18, 2017

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Kransaasvoël |

| Bulgarian | Капски лешояд |

| Catalan | voltor del Cap |

| Czech | sup kapský |

| Danish | Kapgrib |

| Dutch | Kaapse Gier |

| English | Cape Griffon |

| English (South Africa) | Cape Vulture |

| English (United States) | Cape Griffon |

| Finnish | kapinkorppikotka |

| French | Vautour chassefiente |

| French (France) | Vautour chassefiente |

| German | Kapgeier |

| Hebrew | נשר הכף |

| Icelandic | Höfðagammur |

| Japanese | ケープシロエリハゲワシ |

| Norwegian | kappgribb |

| Polish | sęp przylądkowy |

| Russian | Капский сип |

| Serbian | Kapski sup |

| Slovak | sup plavý |

| Slovenian | Kapski jastreb |

| Spanish | Buitre de El Cabo |

| Spanish (Spain) | Buitre de El Cabo |

| Swedish | kapgam |

| Turkish | Kap Akbabası |

| Ukrainian | Сип капський |

Gyps coprotheres (Forster, 1798)

Definitions

- GYPS

- gyps

- coprotheres

- Coprotheres

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

95–110 cm (1); 7070–10,900 g, mean 9350 g; wingspan 228–255 cm (1). Pale plumage contrasts with dark spots along trailing edge of wing-coverts and dark flight-feathers; underparts cream to white (1). Most like G. fulvus but relatively shorter-winged and longer-tailed (1), and neck and bill colour differ. Female is on average barely larger than male (1). Bill black at all ages; adult has eye golden to ivory-coloured, neck and coracoid skin patches blue, and cere blue-grey (1). Juvenile is pale brown, with buff-scaled upperparts, whitish-streaked underparts and ruff, and has eye brown and neck pink; moults to first immature plumage at 10–12 months, and reaches adult plumage only after 6–7 years, although already considerably paler in second year, with orange-brown eyes, latter not becoming yellow until sixth year (1).

Systematics History

Subspecies

Distribution

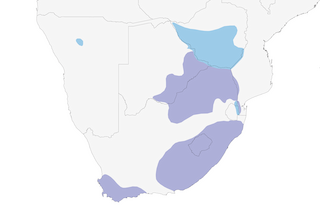

S Africa. Centred on SE Botswana and NE South Africa, and on Lesotho and E South Africa; locally in S Western Cape. Formerly bred also in Namibia, W & S Zimbabwe, W & S Mozambique (where now scarce) and Swaziland; rarely wandering N to Zambia.

Habitat

Open grassland, steppe and, historically, karooid vegetation, in the proximity of mountains for orographic lift and cliffs for roosting and nesting sites. Peripheral N colonies in bush savanna. Recorded from sea-level to at least 3000 m (1).

Movement

Most remain within foraging range of c. 100 km of nesting and roosting colonies, but some evidence of local migrations, e.g. species present in E Cape Midlands (South Africa) only during non-breeding season, and origin (breeding area) of these is as yet unknown (5). There may also be some seasonal effect on foraging range: during winter, at onset of breeding, foraging sites in a South African study were twice the distance from the colony as those used in summer, and a similar propensity to wander farther in winter has been noted in Namibia (6). Some disperse, apparently randomly, over long distances throughout S African subcontinent (e.g. into Angola, Zambia and C Mozambique), especially juveniles which concentrate in nursery areas remote from colonies and regularly range 400–500 km from natal area, more exceptionally 1226 km, reaching as far N as S Zambia and S DRCongo (1). One radio-tagged juvenile from tiny colony in C Namibia that was tracked for six months flew initially to Etosha National Park, from where it wandered into Angola, then to the Okavango of Botswana, and also made a short excursion into Zambia (6). In South Africa, aside from roost sites vulture feeding stations are the most important environmental variable that explains vulture movements; however, the birds range over areas without supplementary food and their mean home range values are comparable to those measured before the inception of feeding stations (7).

Diet and Foraging

Carrion and bone fragments of larger carcasses, mainly soft muscle and organ tissue; in much of range now reduced to feeding on dead sheep, goats, cattle, etc (1). Colonial and gregarious, feeding and fighting among other vultures to obtain flesh, even inserting the long bare neck under the skin or crawling into the rib cage. Dominant over, despite frequently being outnumbered by, G. africanus (1). Often soars in groups (both high and low) (1), using behaviour of conspecifics as an aid to locate food, but also follows Terathopius ecaudatus, Pied Crows (Corvus albus) and White-necked Ravens (Corvus albicollis), as well as jackals and dogs (1). After feeding, usually bathes communally at favourite sites.

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Generally silent except around nest, when gathering at carcasses and at roosts, and calls include a hiss of dominance and an extended, drawn-out nasal bellow, as well as chattering, grunting and asthmatic squeals (1).

Breeding

Laying Apr–Jul, but overall season lasts until Jan (or even Mar) (1). Monogamous (8). Displays consist solely of mutual soaring close to nest-sites and some shallow dives (9). Breeds in colonies of 2–1000 pairs (rarely more than a few hundreds (8), and most colonies in South Africa now fewer than 21 pairs) (10). Nest a platform of sticks, bracken and grass (9) (45–100 cm wide and 20–30 cm deep), densely lined with grass and leaves (1), 15–150 m above ground on open ledge of cliff face (1); some pairs recently reported as nesting in trees at tiny colony in Namibia (6); nest may be reused by same pair in subsequent seasons (9), but more usually a new one is constructed, and nests may be spaced just 2–3 m apart at large colonies (8). Clutch 1 white (9) egg (rarely two), 83·2–98 mm × 63·2–72·5 mm, c. 240 g (9); incubation by both sexes (9), change-over intervals of 1–2-days (8), period 53–59 days (1); chick has white down; parents take turns with care of egg and chick; fledging period c. 125–171 days (8). No records of two chicks fledging (9). In Botswana, productivity known to increase with colony age; over eight-year study in 1990s, eggs laid in at least 436 of 477 nests (91·4%) at Mannyelanong, where chicks survived to mid-season (60–80 days old) in 327 nests (75% of eggs), and fledged in 248 nests (56·9% of eggs laid and 52% of pairs attempting to breed), whereas in E Botswana eggs laid in at least 1825 of 2101 nests (86·9%) and chicks survived to mid-season in 1272 nests (69·7% of eggs) (11); in 1997–1999, of 990 eggs laid in 1108 nests, chicks fledged in 384 nests (38·8% of eggs laid and 34·6% of pairs attempting to breed) (11). Known to have lived for more than 11 years.

Conservation Status

ENDANGERED. CITES II. Has small population seemingly in continuing decline. Considered Vulnerable until 2015, when evidence of more rapid declines came to light, causing elevation of threat status. At least 83 colonies and 4400 breeding pairs estimated to remain in 1994, but has undergone range retraction and loss of peripheral colonies since then; declines (of up to 10% per five years) continue at some major colonies. Estimated global population in 2006 was 8000–10,000 individuals, approximating to 5300–6700 mature individuals; in 2013 estimate revised to 4700 pairs, or 9400 mature individuals BirdLife International (2015) Species factsheet: Gyps coprotheres. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 04/11/2015. . Believed that 18 “core” colonies now hold 80% of current population (12). Even some colonies that increased during 1980s have since declined (13). Overall declines of 92% over three generations (48 years) thought to be occurring (14) BirdLife International (2015) Species factsheet: Gyps coprotheres. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 04/11/2015. .; however, magnitude of global trend obscured by regional variation, e.g. some South African populations are reported to be increasing (15) BirdLife International (2015) Species factsheet: Gyps coprotheres. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 04/11/2015. . Current best estimates of numbers per range state as follows: in South Africa minimum of 630 pairs at 143 historical roosting sites/colonies (62 of them probably now inactive) and 2000 individuals, all in E Cape, with 39% of colonies known in 1987–1992 now inactive or used only for roosting (10) (total in E South Africa thought to have decreased by 60–70% during 1992-2007, and numbers still decreasing throughout country); in Botswana c. 600 pairs (at least 100 pairs at Mannyelanong in SE and c. 500 pairs in E of country) (11); Lesotho has c. 552 pairs at c. 47 colonies BirdLife International (2015) Species factsheet: Gyps coprotheres. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 04/11/2015. , Mozambique 10–15 pairs (near Swaziland border) BirdLife International (2015) Species factsheet: Gyps coprotheres. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 04/11/2015. , and this species is now extinct in Swaziland (small population died out in 1980s or earlier) and as a breeder in Zimbabwe (isolated roost of up to 150 non-breeders persisted through 1990s, but species apparently declined to extinction) and probably lost also from Namibia BirdLife International (2015) Species factsheet: Gyps coprotheres. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 04/11/2015. , where just one tiny colony known in mid-2000s and this being maintained to some extent by establishment of two "vulture restaurants" to supplement the naturally available food (6); in Namibia more than 2000 present in 1950s, but by 2000 only 6–12 individuals remained and, although 16 released in Oct 2005, this vulture now considered extinct in that country BirdLife International (2015) Species factsheet: Gyps coprotheres. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 04/11/2015. . This is the most studied, monitored and conserved of African vulture species. Historically affected by elimination of carnivores (e.g. hyenas) and game, possibly initiating skeletal abnormalities (osteodystrophy) in chicks, through lack of bone flakes in diet; provision of "restaurants" at which crushed skeletons provided to birds has yielded dramatic decline in osteodystrophy in this species (16). Has recently been subject to persecution and inadvertent poisoning, exposure to agro-chemicals (17), loss of foraging habitat due to anthropogenic factors (spread of agriculture, etc.) (17), collection for traditional medicines (especially in South Africa) (17), human disturbance at roosting/breeding sites (17), electrocution on powerlines (quantified at c. 80 individuals per annum in Eastern Cape, South Africa) (18) and drowning in high-walled water tanks (sometimes en masse) (19). Ingestion of poison in baits left for pests (not vultures) causes further mortality, and possible that diclofenac (a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug often used for livestock), fatal to Gyps species when ingested at livestock carcasses, could also be a big problem; in 2007, diclofenac found on sale at veterinary practice in Tanzania, and reported that a Brazilian manufacturer in that country has been aggressively marketing the drug for veterinary purposes and exporting it to 15 African countries; a single poisoning incident can kill up to 100 vultures, making the species highly susceptible to sudden local declines. In some parts of range, e.g. Magaliesberg (in NE South Africa), many fatalities associated with flying into powerlines and electrocution, this being one of main factors behind continuing decline in South Africa; estimate of c. 80 vulture deaths per year at powerlines in Eastern Cape considered lower than true figure. In addition to provision of food and bone flakes at vulture restaurants, and attempts to control limiting agents, conservation efforts have included a successful intervention to prevent military planes approaching colonies too closely (20). Not obviously affected by pesticides. Legally protected throughout range. Some colonies situated within protected areas. A number of conservation organizations have managed to raise awareness among farming communities in South Africa of this species’ plight, and in some regions of that country electricity supplier has introduced a new design of pylon which reduces electrocution risk to large birds. Wind farms may also pose a threat; a study using satellite tracking data coupled with a population viability model suggests that wind farm development in the Lesotho Highlands is likely to result in accelerated population decline and extinction (21). Supplementary feeding at “vulture restaurants” may have slowed declines in some areas; establishment of restaurant thought to have helped to promote recolonization of former colony at Nooitgedacht, in South Africa, and another may have contributed to this species' recovery in Magaliesberg, but degree to which this vulture is dependent on artificial food sources not yet fully studied; supplementary feeding known to have significantly increased survival rate of first-years in Western Cape Province in 1990s. Farmers in Namibia have been made aware of benefits brought by vultures and disadvantages of poisoning carcasses, and education centre and education programme for schools have been set up. Continuous monitoring of all populations essential, and continued public-awareness programmes and supplementary feeding important if this species is not to decline further.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding