Malleefowl Leipoa ocellata Scientific name definitions

- VU Vulnerable

- Names (20)

- Monotypic

Text last updated September 7, 2015

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Catalan | talègol ocel·lat |

| Czech | tabon holubí |

| Dutch | Thermometervogel |

| English | Malleefowl |

| English (United States) | Malleefowl |

| French | Léipoa ocellé |

| French (France) | Léipoa ocellé |

| German | Thermometerhuhn |

| Icelandic | Kjarrhæna |

| Japanese | クサムラツカツクリ |

| Norwegian | malleeovnhøne |

| Polish | nogal prążkowany |

| Russian | Глазчатая сорная курица |

| Serbian | Pegava megapoda |

| Slovak | tabon okavý |

| Spanish | Talégalo Leipoa |

| Spanish (Spain) | Talégalo leipoa |

| Swedish | malleehöna |

| Turkish | Benekli Megapod |

| Ukrainian | Великоніг строкатий |

Leipoa ocellata Gould, 1840

Definitions

- LEIPOA

- ocellata / ocellatum / ocellatus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

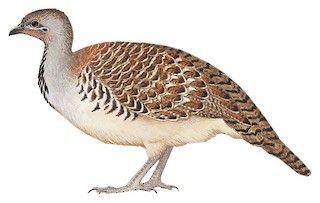

c. 60 cm; male 2000–2800 g (1, 2), female 1520–2050 g. Most distinctive megapode, with pale, patterned plumage ; flattened crest. Predominantly grey-brown below with broad black markings on throat to upper breast , and black, white and chestnut-barred upperparts . Female averages slightly smaller and lighter than male. Iris hazel to brown, orbital skin blue to dusky grey, bill bluish horn to black, and legs and feet blue-grey to blackish brown (2). Immature similar to adult but smaller. Juvenile dull grey-brown, barred cream on upperparts.

Systematics History

E populations sometimes split off into separate race, rosinae. Monotypic.

Subspecies

Introduced to Kangaroo I (off South Australia), where probably now extinct.

Distribution

SW & S Australia E to NW Victoria and EC New South Wales.

Habitat

Woodland and scrub of semi-arid areas in temperate zone, especially areas dominated by dwarf mallee (Eucalyptus), where annual rainfall totals 300–430 mm; less abundant in mallee with lower rainfall of 220–300 mm. Common in areas of mulga (Acacia aneura); also found in areas with other Acacia and Callitris, and in places occurs in dry coastal heath. Optimum habitat apparently has near-complete canopy and often rich layer of shrubs, but is fairly clear at ground level. In NE Victoria, favours patches of tall broombush (Melaleuca uncinata) more than 30 years old. Abundant food required in immediate environs of mound, as male's attention to mound is almost perpetual during certain periods of year (see Family Text). Roosts at extremities of tall shrubs and trees (3).

Movement

Sedentary; male tends mound for 9–11 months of year, at times returning at hourly intervals. In area of low rainfall in South Australia: home range of c. 4 km2; density of 1·1 pairs/ km2. In area of higher rainfall (300–400 mm/year), in New South Wales, during breeding season: males remained within 100 m of mound, females within 250 m. Territory and mound normally abandoned by Apr, but often for little more than one month. Mounds rarely placed on same site during two successive years, but usually within radius of c. 500 m.

Diet and Foraging

Omnivorous, but probably mainly granivorous. Buds, flowers, fruits and seeds of shrubs, especially legumes; also seeds, flowers and leaves of herbs, especially seedlings. Other items recorded include fungi and wide variety of invertebrates, e.g. beetles, cockroaches, dragonflies, bees, ants, spiders; birds do not apparently search actively for invertebrates, which are simply taken whenever encountered. Observations in W New South Wales showed that birds fed on: buds, fruits and seeds (during 73% of observations), especially Cassia eremophila, Acacia and Beyeria opaca (58%); herbs (10%); and insects (17%). In Victoria, observed targets of pecks: 49% herbs; 37% lerps (Glycaspis); 7% fungi (mostly Mycena); and 4% assorted invertebrates; dry weight of crop and gizzard contents of a male in same state heavily biased to two exotic plants: seeds of Silene gallica (c. 49%) and flowers/leaves of Hypochoeris radicata (c. 13·5%), with grit comprising c. 17% (1); in W Victoria, long-term study (26 years) of free-ranging birds recorded total of 19 flowering plants, four fungi and seven invertebrate taxa in diet (4). In South Australia, dry weight of crop and gizzard contents: 53% seeds of Dodonaea bursariifolia, 11% seeds of Cassytha melantha and 22% sand (ingested to help break down food). Considerable seasonal variation in diet: insects mainly in spring; herbs (autumn/winter/spring); buds (winter/spring); flowers (spring/early summer); and seeds (summer/autumn); buds and berries of Beyeria opaca particularly important in spring and summer. Main food types are seeds of legumes in summer, but herbs in autumn and winter. Adults reckoned to require c. 37 g of seeds (300–2200 seeds) per day. Hatchlings can feed on insects on same day as hatching, but some seeds considered important in the diet of adults, e.g. Acacia, are apparently rarely taken by small young (5). See Family Text.

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Most frequently heard is territorial call, usually near nesting mound, a loud booming (by male) rendered “uh-uh-uh-oome-oome-oome”, repeated up to five times and is audible up to 800 m away (2); male lowers head/neck and inflates breast feathers while calling (2). Sometimes pairs duet, with female responding to male's boom with a loud, higher-pitched “waugh waugh” (2). Also gives various grunts (feeding, alarm or mound construction) and low-pitched crooning or clucking (egg-laying) notes (2).

Breeding

Mound building starts Mar–May, but more usually Jun–Aug (2); laying starts mid Sept/mid Oct in W New South Wales. Generally monogamous, with strong pair-bond (lasting at least six years) (2), although male and female generally spend much time apart (2), but one record of polygyny with two females laying 29 and 30 eggs, respectively, in separate mounds ; when one disappeared male remained with the other (6). Mound builder : usually 60–75 cm high, occasionally 150 cm, but 270–450 cm in diameter with circumference of 1350 cm (2). Built mainly by male, using leaves, sticks, bark, debris and sand (usually in areas with good drainage) (2); foundation crater of mound c. 300 cm wide × 90 cm deep; mound temperature relatively constant at c. 29°–38°C (average 33°C), regulated mostly by male ; an abandoned mound retained its 34°C temperature for at least seven weeks (6). Mound tended by male for 9–11 months per year; old mounds (of same or different pair) often dug out and reused, but normally after being left unused for one year or more. Single female normally lays 15–24 eggs (2–34) per season, at average interval of 6·4 days (4–17); incubation averages 62–64 days (49–96). Eggs initially pinkish, but turn buff with age (2). Chick has down above dark brown barred pale buff, below pale brown, with wing feathers well developed; weight at hatching 92–117 g (5), at 20 days 146 g, at 60 days 300 g, at 100 days 450 g, at 200 days 800 g (but can attain this mass prior to 150 days) (3), at 500 days 1580 g (but can be > 1800 g) (3). Hatching success: 79% (for 289 eggs) in zone where no predation of eggs by foxes, though several adults eaten; 49·5% (for 1094 eggs) in area with heavy predation by foxes (37%); 51% (for 530 eggs) in area with limited predation by foxes (5·6%), but many eggs lost in saturated mounds (11%), and many infertile (14%); chick mortality assumed to be very high, even in areas where ground-dwelling predators absent or few (predation by raptors and chilling by rain being major causes of death) (5). Sexual maturity at 3–4 years old (2), in captivity.

Conservation Status

VULNERABLE. Mace Lande: Vulnerable. Total population was thought to number only 1000–10,000 individuals, and to be declining, but at start of 21st century was estimated at c. 100,000 mature individuals. Regionally (under earlier estimate): New South Wales, c. 745 pairs (1985, by which time densities had been reduced tenfold from three decades earlier) (3); Victoria , fewer than 1000 pairs; no figures available for South Australia, but population reckoned to be small; Western Australia presumed to have largest population, but little known; however, some evidence over last decade of a general increase across SW New South Wales and Victoria, numbers may have levelled out in South Australia, and range contraction of 45% reported in Western Australia appears to have been an over-estimate (7). Formerly widespread in suitable habitat from Western Australia to New South Wales and NW Victoria; in 1920s and 1930s also bred as far N as Alice Springs (Northern Territory), and perhaps even further N; now absent or rare in 80% of range: population of SW Northern Territory probably now extinct. Precarious status long ignored, because species locally conspicuous. In New South Wales, range has not apparently shrunk, but population now extremely fragmented; small remnants of mallee in wheatbelt, where species occurs at high densities; larger numbers, at much lower densities, in more intact areas to W, including contiguous reserves of Yathong, Round Hill and Nombinnie, totalling c. 250,000 ha, but most of this is suboptimal habitat; surveys at Round Hill Nature Reserve in 1979–1982 revealed population density of 0·03 pairs/km², as opposed to estimate from 1950s of 0·15–1·54 pairs/km². Main threats are destruction and fragmentation of habitat, effects of grazing livestock, fire and introduced predators, but effects of climate change might also represent a significant threat, at least in parts of range (8). In second half of 20th century much loss of habitat due to conversion for agriculture; extensive clearing of mallee for wheatlands over last century or so; optimum areas of mallee with higher rainfall have mostly been cleared; large areas used for grazing by sheep, and in such areas population of present species found to drop by 80–90%; goats and rabbits also contribute to habitat deterioration. In NE Victoria, cyclical cutting of broombush for fencing material removes a favoured habitat of species; such patches also particularly threatened by periodical bush fires; excessive controlled burning of habitat to improve grazing. Many eggs and young (even subadults) (3) taken by introduced European foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and significant predation by feral cats. Levels of fox predation are significant even in relatively undisturbed habitats: recent study found that overall level of captive-bred Malleefowl survival was better than that recorded in more disturbed habitat in absence of any fox control, but substantially less than that after fox control was implemented (9). Fragmentation of habitat leads to inbreeding, and increases risk of extinction of individual local populations due to catastrophes, natural or man-induced. Several special mallee reserves created; captive breeding in progress, with a view to reintroduction in New South Wales and South Australia (but captive-bred young released into areas with foxes can be quickly wiped out) (3). Extensive survey required, along with constant monitoring of populations; preservation and management of habitat necessary, especially with respect to fire risk (recent study found that the species’ populations are negatively impacted for more than 20–30 years by large fires) (10); competing grazers should be controlled and, in places, removed; introduced predators should be eradicated (baits for foxes using a toxin known to be non-harmful to the birds attempted in various suitable reserves in South Australia, New South Wales, Victoria and Western Australia) (11), although there is recent evidence to suggest that fox baiting is generally not a cost-effective conservation management action (12). See Family Text .

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding