Eurasian Woodcock Scolopax rusticola Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (49)

- Monotypic

Text last updated September 3, 2015

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Albanian | Shapka |

| Arabic | ديك الغاب |

| Armenian | Անտառակտցար |

| Asturian | Arcea euroasiñtica |

| Azerbaijani | Meşə cülütü |

| Basque | Oilagorra |

| Bulgarian | Горски бекас |

| Catalan | becada eurasiàtica |

| Chinese | 山鷸 |

| Chinese (Hong Kong SAR China) | 丘鷸 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 丘鹬 |

| Croatian | šumska šljuka |

| Czech | sluka lesní |

| Danish | Skovsneppe |

| Dutch | Houtsnip |

| English | Eurasian Woodcock |

| English (United States) | Eurasian Woodcock |

| Faroese | Skógsnípa |

| Finnish | lehtokurppa |

| French | Bécasse des bois |

| French (France) | Bécasse des bois |

| Galician | Arcea europea |

| German | Waldschnepfe |

| Greek | Μπεκάτσα |

| Hebrew | חרטומן יערות |

| Hungarian | Erdei szalonka |

| Icelandic | Skógarsnípa |

| Italian | Beccaccia |

| Japanese | ヤマシギ |

| Korean | 멧도요 |

| Latvian | Sloka |

| Lithuanian | Slanka |

| Malayalam | പ്രാക്കാട |

| Mongolian | Буурал хомноот |

| Norwegian | rugde |

| Persian | ابیا |

| Polish | słonka |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Galinhola |

| Romanian | Sitar de pădure |

| Russian | Вальдшнеп |

| Serbian | Šumska šljuka |

| Slovak | sluka hôrna |

| Slovenian | Sloka |

| Spanish | Chocha Perdiz |

| Spanish (Spain) | Chocha perdiz |

| Swedish | morkulla |

| Thai | นกปากซ่อมดง |

| Turkish | Çulluk |

| Ukrainian | Слуква лісова |

Scolopax rusticola Linnaeus, 1758

Definitions

- SCOLOPAX

- scolopax

- rusticola

- Rusticola

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

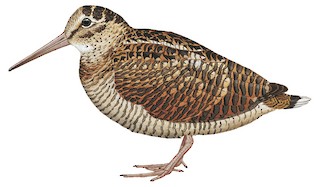

Field Identification

33–35 cm; 131–420 g (mean c. 300 g) (1); wingspan 56–60 cm. Bill long and straight, but relatively shorter than congeners; thick transverse bars on crown, typical for all woodcock species; mainly rufous brown and reddish above providing good camouflage ; broad wings , in flight recalling owl. Plumage somewhat variable; individuals with bill half normal length have been recorded in W Europe, especially since 1970, possibly related to pesticide contamination. Differs from very similar, possibly conspecific, S. mira in having area of whitish feathering around eye , rather than bare skin; rounder head; dark subterminal band on tail; narrower wings and shorter tarsi. Sexes alike, although male tends to have marginally shorter bill and longer tail than female (2). No seasonal variation. Juvenile very similar to adult, but forehead more spotted.

Systematics History

Subspecies

Distribution

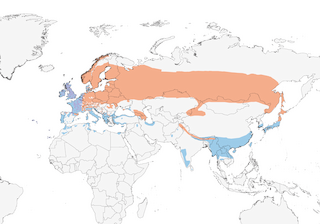

Azores, Madeira, Canary Is and British Is through N & C Europe and C Asia to Sakhalin I and Japan; also Caucasus, NW China and Himalayas (N Pakistan to N Myanmar). Winters from W & S Europe and N Africa to SE Asia. Traditionally considered rare winter visitor to Philippines (Luzon), but recent work indicated that at least some sightings there referred to a previously undescribed species (on Mindanao and Luzon) (see S. bukidnonensis).

Habitat

During breeding season occurs in moist forests , where favours mosaic habitats, and extensive woodland covered by undergrowth of scrub, e.g. of brambles, holly, whin or gorse and bracken; avoids warm and dry areas. Often feeds along streams or springs, or in damp and swampy patches. Recorded to c. 2000 m in breeding season (1). Non-breeding habitat similar to breeding habitat during daytime, but less restricted, e.g. also occupies young conifer plantations, hedgerows and scrub (e.g. in Ireland), but also cane-brakes in marshes, orchards and even sea cliffs on Mallorca (1); avoids habitat with coppice less than seven, or more than 20, years old, or that which lacks coppice; often gathers for roosting and feeding in earthworm-rich permanent grasslands (especially grazed meadows) (3) at night, though use of such areas differs dramatically seasonally, e.g. in UK study 94% of nocturnal radiolocations were on fields in Mar, dropping to 18% in Jul (4). In NE Spain, earthworm abundance is considered to be main criterion in habitat selection at the mesohabitat scale (5).

Movement

Mostly migratory, though perhaps only an altitudinal migrant in Himalayas. Fenno-Scandian and some W Russian birds winter in W & S Europe and N Africa; breeding birds of British Isles and France mainly resident. Satellite-tracking of 20 individuals has shown that birds wintering in N Spain breed on average much further E than previously thought: most were tracked to Russia E of Moscow (6); both ringing recoveries (7) and analysis of stable isotopes in feathers (8) had previously suggested that c. 80% originated from circum-Baltic region. Significant numbers of Russian birds also winter in France (9, 10). Asian breeders winter in Iraq, Iran, Azerbaijan, Afghanistan and India through Indochina to SE China, exceptionally S to Borneo (one definite record, in Sabah, several uncertain reports from Brunei) (11), and occasionally as far N as NE Kazakhstan (12); the few records on Luzon (N Philippines) might reconfirmation, although some relevant specimens from the lowlands (where S. bukidnonensis does not occur) have been lost (13) (there is also a recent possible record on Babuyan Claro) (14). Vagrant to E North America (several records in late 1800s, and one in Jan 1956), with three records from Greenland in 1900s (15); also accidental visitor to Spitsbergen, Bear I, Jan Mayen, Iceland (annual), Cape Verdes (16), Jordan (17) and Arabia S to Oman (1, 18), Bangladesh (19) and Cambodia (20). Timing of autumn departure related to onset of frosts (Oct–Nov); return to breeding grounds, Mar to mid-May, also closely related to temperature, and is therefore becoming earlier as a result of climate change (21). Females migrate first, at least in some areas. Both young and parents often return to previous nesting areas. Migrates nocturnally, usually alone, sometimes in twos and rarely in groups of up to six or more, although birds may be aggregated by weather and/or topography (1). In summer, diurnal home range sizes at two sites in the UK were similar and averaged 62 ha (4).

Diet and Foraging

Mainly animals, with some plant matter, especially in spring (2). Animals include earthworms , insects and their larvae, particularly beetles, but also earwigs; millipedes, spiders, crustaceans, slugs, leeches and ribbonworms. Plant material comprises seeds of buttercups (Ranunculaceae), spurges (Euphorbiaceae), sedges (Cyperaceae), peas (Leguminosae) and grasses (Gramineae) (2), fruits, oats, maize grain and roots and blades of various grasses. Earthworms often dominate diet, but relatively less common on harder soil. Gut contents of 16 birds shot in Iran included insects (37·5%), Myriapoda and gastropods (6·25%) and many seeds (22). Composition of diet and use of habitat may differ between sexes, and chicks (which usually self-feed, except perhaps for brief period after hatching) (23) show strong preference for spiders in some areas (2). However, in UK study, earthworms were most important diet component of adults and chicks in terms of biomass at two sites (50–80%), the rest comprising mainly spiders, harvestmen and beetles (4). Feeds by probing in puddles or damp ground, or by pecking at ground surface, or under leaf-litter and twigs; may use foot-trembling. Often forages at night, especially outside breeding season, when earthworms taken on pasture land may predominate. However, recent French study found that winter foraging strategies vary individually, some birds (34% in one study) remaining faithful to one site, others (48%) moving around a series of core sites and still others (18%) constantly changing locality without returning to the same one, with many birds also foraging diurnally inside forest and only electing to feed nocturnally depending on their success during daylight (83% of birds used meadows on > 70% of nights during a study in W France) (24, 25).

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Male’s roding song (see also Breeding) usually comprises 2–5 slow but accelerating deep croaking or growling sounds, followed by a sudden sneezing note, before the sequence is repeated after a pause of 2–2·5 seconds; accompanying flight is characterized by slow, very deliberate-looking wingbeats, with bill head downwards, over wide area of woodland and adjacent open ground, to which female may respond by giving softer version of sneezing note from ground, or by flying silently at canopy level or below it (male above this), whereupon both birds may give “chhrr” calls; either bird may also give muffled, quick “bibbibbibbibbib”, both in flight, or on ground during courtship. Males are individually variable in terms of their vocal displays, and can be identified in the majority of cases, enabling accurate surveys of numbers of different males within an area (26). In non-breeding seasion, when flushed, or in regular flight, gives a harsh (and snipe-like) “schaap”, including at night.

Breeding

Lays from early Mar to mid Apr, late nests to mid Jul, exceptionally even Sept (2), but young have been recorded as early as mid Mar in UK (27). It has been suggested that later broods are reared by younger individuals (27). Polygynous mating system, with pair-bond generally lasting just 3–4 days (occasionally up to 11) (1); from Feb, male performs self-advertising display flight (roding flight) around dusk and dawn, especially the former, each flight lasting on average 6–8 minutes with birds generally making 2–5 flights per evening, but flights may continue periodically throughout night if moonlit (2). Males faithful to breeding areas (28). Nest a shallow depression in ground concealed by shrubs, 12–15 cm in diamenter and 2–5 cm deep, lined with dead leaves, dry grass and feathers (1). Clutch four eggs (2–5) (2), laid at interval of 24–48 hours, pale buff to pink-brown with brown or chestnut spots (1), mean size 44·2 mm × 33·5 mm (29); normally single brood, very rarely two, and females will often re-lay if first attempt fails, usually in different site up to 10 km away (2); incubation 22 days (17–24) (2), by female only, starting with last egg (29); chick pale pinkish buff with large, ferruginous-brown and chestnut-brown blotches and bands above, mass 16–20 g on hatching (2); fledging 15–20 days, when mass is c. 50% of adult’s (2); female alone cares for young, and occasionally claimed to carry young chicks between feet and belly during flight (see Family Text). On average 2·3 hatchlings and 1·8 fledglings per nest, while clutch survival from laying to hatching has been estimated at 44–50% and chick survival to fledging at 56% in UK (2, 30). Desertion and predation are main causes of failure, at least in UK, where Eurasian Sparrowhawks (Accipiter nisus) and Tawny Owls (Strix aluco) kill adults, egg predators include Eurasian Jays (Garrulus glandarius) and Carrion Crows (Corvus corone), more occasionally wood mice (Apodemus sylvaticus), grey squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) and hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus), while red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and stoats (Mustela erminea) will usually take both the female and eggs (2). Brood parasitism by Ring-necked Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) has also been reported (31). Males start roding in first year and females are capable of breeding at this age (2). Annual adult survival 0·39–0·63, typically lower in first-year birds (which are more susceptible to hunting) by up to 23% (2, 32, 33). Apparently, nine-year cycle exists in numbers of W European wintering birds, peaks coinciding with high proportion of juveniles in population; this might be result of an eight-year cyclical abundance of a major predator or of this predator’s main prey.

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). African and European post-breeding population estimated at 15,000,000–37,000,000 birds (1982); c. 310,000 pairs estimated breeding in Fenno-Scandia (1986), of which 30,000–50,000 in Norway, 50,000–100,000 in Sweden and 100,000–200,000 in Finland (1); elsewhere in Europe, as many as 10,000,000 pairs have been estimated in Russia, and 200,000–240,000 pairs in Belarus (1); population of Asia unknown. Small increases in NW Europe from 1930 to 1970, probably due to climatic changes and population shift from E to W, including doubling of Irish population (from low base) and other increases registered in Belgium (due to cessation of hunting), Denmark, Netherlands and Spain (1), although more recently the British population declined by > 60% during the final third of the last century (34, 35), with an additional decline during 2003–2013 (36). However, on Azores, Canaries and Madeira populations are declining, with breeding now only sporadic on Santa Maria and Graciosa (Azores), and remains fairly common only on La Gomera (37) Decreases also reported from Germany (until mid 1980s, since when population has been stable at 20,000–39,000 pairs) (38), Latvia, Switzerland, Albania, Bulgaria and Ukraine (1). From 1970s, substantial decline in large wintering population in France, probably due to excessive hunting on migration and wintering grounds; decrease in wintering numbers also reported in Italy, but those in Britain (potentially up to 800,000) thought to be stable (1). Up to 3,700,000 individuals hunted annually in Europe, with 1,500,000 in Italy, 1,300,000 in France, 400,000 in W Russia and 200,000 in Britain, and there have been suggestions that such harvests are unsustainable and should be regulated (33). No clear trend in European breeding population; numbers wintering in Morocco seem stable since 1950s; numbers declining in several regions of Russia, with 3–6-fold decreases locally during last 10–15 years; formerly occurred in summer in Azerbaijan, presumably breeding, and might still breed there. Perhaps breeds in N Turkey, where birds observed roding in spring (39), and breeding recently confirmed in Greece (1). Increased fragmentation of woodlands might explain decline in some areas in Britain and C & N Europe; changes in landscapes and intensive agricultural practices are also threat, especially destruction of hedges, decrease of permanent grazed meadows and impoverishment of soils from ploughing and chemical applications, although the species may benefit from development of set-asides, grass field-borders and simplified farm practices (no-tillage and direct sowing) (3). Prolonged cold spells in winter can lead to high mortality, as their feeding sites become frozen (2), and mortality at this season is positively correlated with mean nocturnal temperatures; in France, survival ranged from 74% in winter 1985/86 to 83% in winter 1994/95 (32). Disappearance of permanent grasslands is a threat to wintering birds; in France, this involves 160,000 ha per year. Appearance in recent years of short-billed individuals, which sometimes also show malformations, may be caused by some pesticides having teratogenic effect.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding