Pied Kingfisher Ceryle rudis Scientific name definitions

Text last updated July 8, 2013

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Bontvisvanger |

| Arabic | صياد السمك أبقع |

| Armenian | Խայտաբղետ ալկիոն |

| Assamese | পখৰা মাছৰোকা |

| Azerbaijani | Ala balıqcıl |

| Catalan | alció garser |

| Chinese | 斑翡翠 |

| Chinese (Hong Kong SAR China) | 斑魚狗 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 斑鱼狗 |

| Croatian | pjegavi vodomar |

| Czech | rybařík jižní |

| Danish | Gråfisker |

| Dutch | Bonte IJsvogel |

| English | Pied Kingfisher |

| English (United States) | Pied Kingfisher |

| French | Martin-pêcheur pie |

| French (France) | Martin-pêcheur pie |

| German | Graufischer |

| Greek | Κήρυλος |

| Gujarati | કાબરો કલકલિયો |

| Hebrew | פרפור עקוד |

| Hindi | "चित्ता किलकिला," |

| Hungarian | Tarka halkapó |

| Icelandic | Skjaldþyrill |

| Italian | Martin pescatore bianconero |

| Japanese | ヒメヤマセミ |

| Lithuanian | Margasis tulžys |

| Malayalam | പുള്ളിമീൻകൊത്തി |

| Marathi | कवड्या धीवर |

| Norwegian | terneisfugl |

| Odia | ଦୋବ ମାଛରଙ୍କା |

| Persian | ماهی خورک ابلق |

| Polish | rybaczek srokaty |

| Portuguese (Angola) | Pica-peixe-malhado |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Guarda-rios-malhado |

| Punjabi (India) | ਕਿਲਕਿਲਾ |

| Romanian | Pescăraș pestriț |

| Russian | Малый пегий зимородок |

| Serbian | Vodomar šarac |

| Slovak | rybárec strakatý |

| Slovenian | Črnobeli pasat |

| Spanish | Martín Pescador Pío |

| Spanish (Spain) | Martín pescador pío |

| Swedish | gråfiskare |

| Telugu | నీటి బుచ్చిగాడు |

| Thai | นกกระเต็นปักหลัก |

| Turkish | Alaca Yalıçapkını |

| Ukrainian | Рибалочка строкатий |

Ceryle rudis (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- CERYLE

- rudis

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

25–30·5 cm; male 68–100 g, female 71–110 g. Distinctive medium-sized kingfisher with black-and-white plumage. Male nominate race black crown and crest, white stripe above eye, black eyeband to hindneck, white throat and collar; black upperparts with white edgings, rump barred black and white, white patch on wing-coverts ; white below with two black breastbands, the upper broad and often almost broken in middle, lower one narrower; bill almost entirely black; iris dark brown; legs and feet blackish. Adult female only single breastband, narrower and often broken in centre. Juvenile like female, but brown fringe to feathers on lores, chin, throat and breast. Race leucomelanurus has blacker upperparts, black spots on flanks and side of throat; <em>insignis</em> like previous but longer bill; travancoreensis even blacker upperparts, more black spots on flanks and side of throat, longer bill.

Systematics History

Editor's Note: This article requires further editing work to merge existing content into the appropriate Subspecies sections. Please bear with us while this update takes place.

Authorship of race travancoreensis previously given erroneously as Whistler & Kinnear (1). Populations from Turkey and Levant countries E to SW Iran described as race syriacus, but differences from nominate considered questionable; further study needed. Four subspecies recognized.Subspecies

Ceryle rudis rudis Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Ceryle rudis rudis (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- CERYLE

- rudis

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Ceryle rudis leucomelanurus Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Ceryle rudis leucomelanurus Reichenbach, 1851

Definitions

- CERYLE

- rudis

- leucomelanura / leucomelanurus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Ceryle rudis travancoreensis Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Ceryle rudis travancoreensis Whistler, 1935

Definitions

- CERYLE

- rudis

- travancoreensis / travancoriensis / travencoreensis

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Ceryle rudis insignis Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Ceryle rudis insignis Hartert, 1910

Definitions

- CERYLE

- rudis

- insignis

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

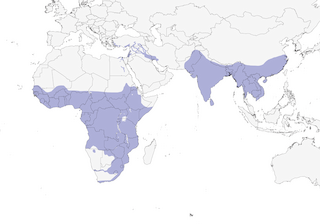

Distribution

Editor's Note: Additional distribution information for this taxon can be found in the 'Subspecies' article above. In the future we will develop a range-wide distribution article.

Habitat

Small and large lakes, large rivers, estuaries, coastal lagoons, mangroves and sandy and rocky coasts, dams and reservoirs with either fresh or brackish water; also streams and smaller fast-flowing rivers, marshes and paddyfields, and even feeding from roadside ditches. Requires waterside perches such as trees, reeds, fences, posts, huts and other man-made objects; large papyrus swamps in Uganda and the centre of open floodplains in Zambia are avoided. From coast to 2500 m in Rwanda, coast to 1800 m in India.

Movement

Generally sedentary. Many reports of seasonal changes in abundance, but these likely to be in response to changes in food availability rather than regular movements. Will arrive within a few days when dry rivers start flowing or when ephemeral pans fill. In non-breeding season, local movements can extend over several 100s of km. Also some observations of mass movements, but some of these may be of birds flying to large roosts of over 100 individuals. In Malawi, females tended to remain on nesting areas associated with rocky shores, while males tended to disperse farther, into areas with sandy shores. One bird ringed in Ethiopia was recovered in Uganda, 760 km away. A few records from Cyprus, Greece, SE Russia, Spain, Sicily and Poland.

Diet and Foraging

Largely fish in Africa, including Engraulicypris argenteus, Haplochromis, Barbus and Clarius at L Victoria; Haplochromis, other cichlids, Barbus paludinosus in Botswana; in South Africa, Ambassis natalensis, Gilchristella aestuarius and many other species in Kosi Estuary, and also Sarotherodon mossambicus at L St Lucia; Barbus, Alestes and cichlid species in Zambia, and cichlids Cyrtocara eucinostomus and Pseudotropheus zebra in Malawi. Preferred size range of fish 25–60 mm, but those up to 133 mm and 26 g are taken. Aquatic insects may supplement this, and dragonfly nymphs (Anisoptera) were 24% of all prey items on Kafue Flats, in Zambia; also winged insects, e.g. adult dragonflies, alate termites (Macrotermes); and grasshoppers (Ruspolia flavovirens), water beetles (Dytiscidae, Gyrinidae), water scorpions (Nepidae), water-bugs (Notonectidae, Corixidae, Belostomatidae); 2 birds flushed from a carcass in Tanzania were probably feeding on maggots. In the Sundarbans of India, fish included Mugil parsa, Ambassis, Puntius and Mystus, with crabs and crayfish (17% of prey) and aquatic insects (26%) also taken. Frogs, tadpoles and molluscs also recorded, though latter may be secondarily ingested. Average daily food intake estimated to be 18·4 g (24·6% of body weight), representing 7·2 fish/bird/day; 2 hand-reared juveniles near to fledging also had daily intake of 24–26% of body weight, but younger captive nestlings ate 34·5 g/day (45% of body weight). Pellets consisting of undigested bones and insect sclerites are produced at night and during resting periods during day, prior to resuming foraging. Hunts by scanning from perch , bobbing head and flicking tail, and then diving down, hitting water with a splash, returning with prey carried crosswise in its bill. Small fish may be swallowed in flight; larger ones (over 55 mm) taken back to perch and bashed repeatedly, up to 113 times for a 9-cm Tilapia, before being swallowed head first. Also regularly hovers, before plunging down to take prey in water; in still, calm conditions hovering used for 20% of dives, increasing to 80% in windy conditions. In Malawi, hovering was used for 98% of foraging on sandy beaches where perches rare, but for only 5% on rocky shores where perches common. Hovering allows it to go out over 3 km from shoreline; flies low over water then rises 2–10 m, with body nearly vertical, bill held down and wings beating rapidly; may move or drop down slightly and resume hovering before diving down; if successful, will swallow prey on the wing without prior beating on branch. Feeding success was 55% for dives from a perch and 41% from hovering on L Victoria, but only 18% on L Malawi with no differences between foraging methods. On L Kariba, usual daytime feeding patterns with 4–5 peaks were moved to dawn and dusk to take advantage of sardine (Limnothrissa miodon) rising to surface; in Kashmir, was most active 08:00–09:00 and 16:00–18:00 hours. On land it will take termites on the wing, and will also dive to the ground to catch insects. Seen to hover over a clawless otter (Aonyx capensis), presumably watching for displaced fish. Sometimes uses hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) as a perch.

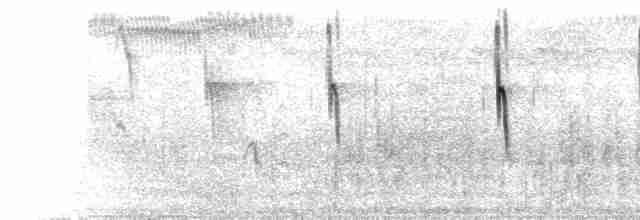

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Alert call, frequently given in flight or from perch, “kwik-kwik” or “chirruk, chirruk”; alarm low-pitched “trrr trrr trrr”; distress call shrill, rapidly repeated “preepreepreepree”; contact call, arriving or leaving nest or roost, “tréétiti, tréétiti”; advertising call, given in defence of nest-site or perch, high-pitched “chíckkerker”; aggressive call shrill repeated “shreeur”; appeasement “werk...werk. werk.. werkwerkerkerk erk”; begging call brief repeated “pi-chee”; courtship-feeding calls soft warbled sounds and chirps; copulation call very soft “pirree”.

Breeding

Lays in Aug–Sept in Turkey, in Jun in Iraq, in Mar–Jun in Kashmir; mainly Feb–Apr in N India and mainly Nov–Apr in SE, in Mar–May in Sri Lanka, in Oct–Dec in Myanmar, in Dec–Mar in Thailand, and in Feb–May in SE China; in Mar–May in Egypt, in Sept–Apr in Senegambia, in Nov–Mar in Ghana and Nigeria, in Dec and May in Ethiopia; all months but mainly Mar–Jul in E Africa; in Feb–Dec (mainly Jun) in Zambia, in Jun–Sept in Malawi, in Jul–Apr (mainly Sept–Oct) in Zimbabwe, in Apr–Oct in N Botswana and Namibia, and in Aug–Apr in South Africa. Breeds in pairs, or in family groups consisting of primary helpers (1-year-old son of one or both of nesting pair) and/or secondary helpers (unrelated males which not breeding), seldom more than 1 primary helper but can be several secondary in areas with poor food resources; primary helper involved at onset of breeding, bringing food to one of the pair, also helps to mob predators, joins in communal displays and helps to feed nestlings; secondary helpers initially driven off by male but more likely accepted soon after eggs hatch, particularly if food scarce. Solitary or in colonies of usually under 20 nests, but up to 100 reported in Zambia, colonial nests 0·5–5 m apart and defended by pair. Initial displays include aerial chases of 3–8 birds high over colony, then landing and displaying on open land with wing-spread posture and advertising calls, sometimes leading to a fight; male courtship-feeds female during nest-digging, laying and incubation; mating usually near nest, often follows courtship feeding. Nest in earthen bank, over water or up to 1 km from it, occasionally in flat grassy ground; excavated by pair and any primary helper by jabbing at soil with partially opened bill and then kicking soil backwards with legs; digging of tunnel usually takes c. 26 days (11 days to 11 weeks) and up to 80% of short holes without an egg chamber are dug; definitive nest-tunnel usually 1–2·5 m long, longer in sandy soil, straight, horizontal or slightly inclined, and ends in unlined chamber 45 cm long, 24 cm wide and 15 cm high; nestlings dig soil from walls for sanitation, so chamber becomes wider and lower with time. Clutch 1–7 eggs, usually 4–5, laid daily, starting c. 3 days after burrow complete; incubation period 18 days, starting with first egg, so hatching asynchronous over c. 3 days; female parent incubates and broods exclusively at night and also major part of day, assisted by male; young hatch blind and naked, initially fed mainly by male parent and any helpers, later also by female; nestlings fledge at 23–26 days, and 14 days later can fish for themselves, but stay with parents for several months. Breeding success 45–50%; in E Africa, first-year mortality of males was 51%, and for adults average annual mortality was 45% in males and 54% in females. Sexually mature in first year, but some males do not breed until second year or later. Yearling females do not return to natal colony, and fewer adult females than males return to breed in same colony.

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened. Widespread, and one of the most numerous kingfishers in the world. Densities of 9–16 individuals/km were reported along the Kazinga Channel in Uganda, and 3–6/km on L Malawi. On lakes of Uganda, Rwanda and elsewhere, densities of 2 birds/km of shoreline or less are more typical. Numbers have increased with the introduction of fish-stocking and fish-farming in several areas, and populations increased at Kampala, Uganda, by using sandpits for nesting. Has probably benefited from the construction of dams in many areas. Decreases in populations reported from parts of Syria, Israel and Egypt. In Botswana survived the spraying of endosulphan to control tsetse flies (Glossina), but elsewhere has been badly affected by the use of poisons to kill fish and Red-billed Queleas (Quelea quelea). Use of pesticides in sugar-growing areas of SE Zimbabwe may have led to widespread decline.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding