Fieldfare Turdus pilaris Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (45)

- Monotypic

Text last updated January 13, 2013

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Albanian | Tusha e madhe e fushës |

| Arabic | سمنة الحقول |

| Armenian | Սինակեռնեխ |

| Asturian | Malvñs paniegu |

| Azerbaijani | Xallı qaratoyuq |

| Basque | Durdula |

| Bulgarian | Хвойнов дрозд |

| Catalan | griva cerdana |

| Chinese (SIM) | 田鸫 |

| Croatian | drozd bravenjak |

| Czech | drozd kvíčala |

| Danish | Sjagger |

| Dutch | Kramsvogel |

| English | Fieldfare |

| English (United States) | Fieldfare |

| Faroese | Fjalltrøstur |

| Finnish | räkättirastas |

| French | Grive litorne |

| French (France) | Grive litorne |

| Galician | Tordo real |

| German | Wacholderdrossel |

| Greek | Κεδρότσιχλα |

| Hebrew | קיכלי אפור |

| Hungarian | Fenyőrigó |

| Icelandic | Gráþröstur |

| Italian | Cesena |

| Japanese | ノハラツグミ |

| Korean | 회색머리지빠귀 |

| Latvian | Pelēkais strazds |

| Lithuanian | Smilginis strazdas |

| Mongolian | Дуулгат хөөндэй |

| Norwegian | gråtrost |

| Persian | توکای پشت بلوطی |

| Polish | kwiczoł |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Tordo-zornal |

| Romanian | Cocoșar |

| Russian | Рябинник |

| Serbian | Drozd borovnjak |

| Slovak | drozd čvíkota |

| Slovenian | Brinovka |

| Spanish | Zorzal Real |

| Spanish (Spain) | Zorzal real |

| Swedish | björktrast |

| Turkish | Tarla Ardıcı |

| Ukrainian | Чикотень |

Turdus pilaris Linnaeus, 1758

Definitions

- TURDUS

- turdus

- pilaris

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

24–28 cm; 81–141 g. Gregarious, noisy large thrush. Has grey head and rump , brownish-chestnut mantle, back and upperwing-coverts, blackish tail, blackish lores, cheeks, malar and neck patch; white below, breast with orange-buff wash and black streaks , flanks with buff wash and black spots ; white underwing-coverts ; bill yellowish, dark tip; legs blackish. Sexes similar. Juvenile is more uniform brownish-grey above with buff scapular streaks, much stronger spotting below .

Systematics History

Subspecies

Distribution

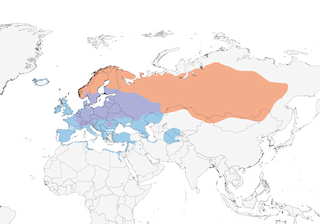

N & C Europe E through C Siberia, N Kazakhstan, Altai and Sayan Mts to Aldan Basin and Transbaikalia; winters in W & S Europe, N Africa and SW Asia.

Habitat

Typically mixed habitat, mainly part-wooded and part-open country , commonly using trees for breeding and roosting, hedges and open ground for foraging; in particular, areas of permanent grass cover much preferred to temporary grass crops, winter cereals, stubble or bare ground; in extreme conditions may forage along beach high-water mark. Breeds in boreal forests of mixed pine (Pinus) and birch (Betula), also scrub, clearings, parks and gardens; in high latitudes extends in relatively small numbers beyond tree-line into alpine heathland and tundra scrub, and even to entirely bleak grassy islands in extreme N. Elevational limits unpredictable; in E Alps, in Europe, highest known breeding site was at 1300 m, but by 1984 breeding occurred at 2310 m. Winters mostly in lowlands, in often more open habitats, including grassy and cultivated fields, especially rough pasture and arable land within easy reach of tall trees and thick hedgerows, also moorland edges, woodland edges and orchards; roosts communally in conifers, deciduous woods, shrubs, reeds and hedgerows (often with other Turdus species), sometimes on ground in open. Outside breeding season favours watersheds with large, low-lying floodplains which provide good winter resources of soil invertebrates and fruit.

Movement

Migratory, but movements essentially irruptive and nomadic, so that overall nature of these complex and variable. In Norway, autumn and winter temperatures, and rowanberry production, influence degree of emigration; in some years significant proportion of breeding population remains in the country. In autumn, early migrants (Jul–Aug) mainly birds of the year, with bulk of adults moving later (mainly Sept–Nov). Migrates both by day and by night, mostly in small parties, sometimes large loose flocks. From breeding areas in N Europe migrates W & S (initially often WSW, then increasingly S) to winter in S Europe ; longest recorded migration by four juveniles, which flew 6100 km from E Siberia to W France. Some, however, remain in more N areas, and mid-winter movements of large numbers may occur there, evidently as conditions in certain quarters become harsher. Presence in winter in N Africa dependent on weather, common when winter in Europe harsh but rare or absent when mild there; generally Oct–Mar, but very variable. In Israel, where absent or common depending on year and weather, passage mainly mid-Nov to mid-Dec and Feb. In S of its winter range tends to be irregular in numbers, with influxes determined by weather farther N, e.g. major influxes in Italy in 1936/37, 1952/53 and 1965/66. Little evidence of site-fidelity or flyway-fidelity, with few retraps of ringed individuals at same stations; one ringed in E Germany in Feb 1979 was in Greece in Feb 1981, and another wintering W Germany visited Cyprus in following year. Some Asian breeders winter in China, and the species is now known to pass through Mongolia. In spring, males tend to move back towards breeding areas well in advance (typically a week) of females; first-years tend to be later than older birds. Spring arrival on breeding grounds in Germany late Feb to late Mar; in Norway arrivals span second week Apr to third week May, depending on latitude and altitude. Records from non-breeding parts of range in Jun and Jul suggest oversummering non-breeders. Vagrants or occasionals recorded S to Atlantic islands, Arabia, India and Japan; casual in Canada.

Diet and Foraging

Invertebrates, and fruits found mainly in bushes and hedgerows. Invertebrates found mainly in and on soil in open fields, include earthworms , snails, slugs, leeches, millipedes (Diplopoda), centipedes (Chilopoda), harvestmen (Opiliones), spiders, beetles (Coleoptera), bugs (Hemiptera), crickets (Orthoptera), caterpillars, flies (Diptera), ants (Hymenoptera) and dragonflies (Odonata), very rarely (e.g. in near-freezing weather) small fish; fruits, berries and seeds eaten in winter, also shoots and buds in spring. Vegetable material extensive, variable with geography and season, includes fruits and/or seeds of apple (Malus, including M. sylvestris), barberry (Berberis vulgaris), bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus), cowberry (V. vitis-idaea) and cranberry (V. oxycoccus), bird cherry (Prunus padus) and other cherries and plums including blackthorn (P. spinosa) and gean (P. avium), black bryony (Talus communis), bramble (Rubus fruticosus), cloudberry (R. chamaemorus), dewberry (R. caesius) and raspberry (R. idaeus), buckthorn (Rhamnus catharticus), cotoneaster (Cotoneaster cornubia), crowberry (Empetrum nigrum), currant (Ribes, including R. uva-crispa), elder (Sambucus nigra), Viburnum including guelder rose (V. opulus), hawthorn (Crataegus), holly (Ilex aquifolium), honeysuckle (Lonicera periclymenum), ivy (Hedera helix), juniper (Juniperus), lime (Tilia cordata), mezereon (Daphne mezereum), mistletoe (Viscum album), oleaster (Elaeagnus angustifolia), olive (Olea europaea), pear (Pyrus communis), pinks (Dianthus), privet (Ligustrum), rose (Rosa, including R. canina), rowan (Sorbus aucuparia), sea-buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides), shadbush (Amelanchier), snowberry (Symphoricarpos rivularis), spindletree (Euonymus europaeus), strawberry (Fragaria), sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus), whitebeam (Sorbus), virginia creeper (Parthenocissus), vine (Vitis), yew (Taxus baccatus), sedges and grasses. Key elements are local abundance and food quality; in one winter study in UK, fed on the smallest number of different fruits, taking just twelve species, of which only four (forming 96% of all records) were highly important, in changing temporal sequence, hawthorn crucial in Oct–Nov, replaced by hips of dogrose Dec–Feb and ivy Mar–May, with holly important in very cold weather. In other studies, other fruits have figured as major foods. A key food in Scandinavia is rowan, which superabundant in some years (can then delay migratory populations until stocks significantly depleted). Among invertebrates, takes more in-soil items than on-soil ones, and earthworms commonest prey in summer quarters (Sweden), while in winter (Britain) food 37·5% insects, 36% fruits and seeds,14·5% earthworms, 5% other plant material, 4·5% slugs, 2·5% other invertebrates. In another study of winter diet in UK, 44% on-soil items (flies, beetles, spiders) and 56% in-soil items (earthworms, centipedes, slugs, beetle and tipulid larvae); as spring advanced, on-soil prey items became larger and their proportion in diet increased to 75%, indicating that size of prey was critical in foraging choice. Study in Norway found invertebrates to be main food in spring and autumn, but with change in composition from (spring) earthworms, adult beetles and ants, supplemented by berries of heath (mainly cowberry) and juniper, to (autumn) adult beetles, harvestmen and ants, supplemented by berries of crowberry and rowan; earthworms particularly important to females in spring; also, earthworms preferentially fed to young, along with tipulids, stoneflies (Plecoptera) and caterpillars. Forages mainly on ground , but also in trees and bushes; rarely hawks insects in air. Very rarely, scratches in leaf litter in manner of T. merula. In observations of feeding on fruit, used hovering in only 1·2% of attempts.

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Song a tuneless chattering scratchy medley of squeaks, chuckles, wheezes, trills and chitters with harsh call notes admixed; sometimes given in flight at start of breeding season. Subsong fainter, more guttural and warbling. Call a loud 2-note or 3-note “shak-shak-shak”; “huii-huit” on migration, soft “quok” as warning at ground predator, deep “wu wu” in threat, agitated “tjetjetjetje” in alarm.

Breeding

Early Apr to late Aug throughout range, varying with latitude, in N areas timing linked to disappearance of snow cover; commonly double-brooded in Switzerland, rather rarely so elsewhere. Monogamous, pairing rapid and courtship without ceremony; extra-pair copulations probably very common; conspecific brood parasitism occurs, in one study 11·5% of nests had eggs laid by another female. Sometimes solitary breeder, especially in S of range, but commonly in colonies with nests 5–30 m apart, largest known colonies (in Norway) containing hundreds of pairs, but most much smaller, and breeding dispersion such that sometimes difficult to judge whether nesting colonial or solitary; fluctuations in colony size result from different causes of mortality, nest predation selecting for larger colonies (mobbing of predators more effective), but chick starvation (caused by over-exploitation of local resources) and adult predation selecting for smaller colony size; fluctuations in position of colony site presumably relate to local conditions. Territory size variable, usually very small, especially for pairs in middle of colony; solitary nesters may defend c·1 ha, whereas colony-nesters usually defend only the nest tree (rarely ever two nests in same tree). Nest a bulky, untidy cup, deeper at higher latitudes than at lower ones, made of twigs , roots, moss, lichen, grass and leaves, lined with animal hair, rootlets and fine grass, and cemented with mud; placed in fork of tree or against trunk or on branch, usually towards upper levels of tree and normally at least 2 m off ground, occasionally on ground, sometimes in cliff face; usual nest heights 7–10 m in C & E Europe, whereas average in Scandinavia and Russia 4–5 m (owing either to lower trees or to lower human density, or both, in latter areas); larger females tend to nest higher than do smaller ones, and larger eggs found in higher-placed nests than in lower ones, suggesting that fitter individuals select greater heights in trees, but nests in colonies tend to be at same heights and in same tree species; in areas with sparse tree cover, nests sometimes placed on beam of abandoned building, bridge strut, window sill, fence, pylon or roof; up to 71% of colonies in N Norway associated with breeding Merlins (Falco columbarius), as a means of harnessing the raptor’s aggression towards potential predators. Eggs 3–7, usually 5–6 (5 commoner at lower latitudes, 6 at higher, but number decreasing with altitude), pale blue with fine speckles, spots and blotches of reddish-brown; incubation, often starting from third egg, 12–15 days, average 13 days; nestling period 12–15 days; post-fledging dependence generally c. 15 days, but up to 30 reported; fledglings spend first 4 days close to nest until better able to fly. Of 758 nests in Germany, 40% produced fledged young, average 1·8 young per nest and 4·6 young per successful nest; average number of fledglings per successful nest in Norway, 1967–1975, varied from 3·7 to 5·05. Nest predation very common, and adults attack avian predators (raptors, crows) with aggressive dive-bombing flights, often terminating with faecal spraying; mammalian nest predators are frequently successful despite mobbing, especially at larger colonies; ground-nesting pairs in alpine heathland much less aggressive and more discreet, presumably because nests far less conspicuous; body condition of adults, variable with year, also influences degree of aggression. Annual mortality 60–70% in Switzerland, 61–65% in Finland; causes of mortality of ringed individuals in NW Europe are natural causes 10%, human-related (accidental) 13%, human-related (deliberate) 58%, other 19%.

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened. Common. Global population many tens of millions, with substantial increase in numbers in Europe in past 100 years and no known commensurate decline elsewhere in range; but numbers vary annually, and extrapolations highly speculative. Colonized Germany 1850–1900, Switzerland 1923, Greenland (apparently) 1937, Hungary 1947, Iceland 1950, French Jura 1953, Denmark 1960, Romania 1966, Britain 1967, Italy and Belgium 1968, Netherlands 1972, former Yugoslavia 1975, Greece early 1980s, Macedonia 1986. National population estimates include 560,000 pairs in Finland, 1,500,000 pairs in Sweden and probably similar figure in Norway, 1,000,000 pairs in Germany, 10,000 pairs in Belgium (in 1983) and a similar figure in France, and 700 pairs in Netherlands (in 1990), yielding a speculated 5,000,000 pairs for W Europe. In 2000, total European population judged to be 14,000,000–24,000,000 pairs and considered generally stable. Given a breeding range of c. 10,000,000 km² and breeding density of 1–3 pairs/km², a global population of up to 60,000,000 adults is possible, with twice this number predictable at end of a good breeding season. Capacity for population increase notable, e.g. mean increment in Belgium, 1968–1983, was 670 pairs per year. Estimated wintering total in UK 1,000,000 individuals. Recently colonized subalpine zone of Altai Mts. In S Greenland, a few bred since 1937 but apparently exterminated by severe winters in 1960s; possibly still breeds.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding