Brown Creeper Certhia americana Scientific name definitions

Text last updated September 3, 2013

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Bulgarian | Американска дърволазка |

| Catalan | raspinell americà |

| Croatian | američki puzavac |

| Dutch | Amerikaanse Boomkruiper |

| English | Brown Creeper |

| English (India) | American Treecreeper |

| English (New Zealand) | American Brown Creeper |

| English (United States) | Brown Creeper |

| French | Grimpereau brun |

| French (France) | Grimpereau brun |

| German | Amerikabaumläufer |

| Icelandic | Trjáfeti |

| Japanese | アメリカキバシリ |

| Norwegian | amerikatrekryper |

| Polish | pełzacz amerykański |

| Russian | Американская пищуха |

| Serbian | Američki puzić |

| Slovak | kôrovník lesný |

| Slovenian | Rjavi plezalček |

| Spanish | Agateador Americano |

| Spanish (Honduras) | Trepadorcito de Ocotal |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Trepadorcito Americano |

| Spanish (Spain) | Agateador americano |

| Swedish | amerikansk trädkrypare |

| Turkish | Amerika Tırmaşıkkuşu |

| Ukrainian | Підкоришник американський |

Certhia americana Bonaparte, 1838

Definitions

- CERTHIA

- certhia

- americ / americana / americanum / americanus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

“The brown creeper, as he hitches along the bole of a tree, looks like a fragment of detached bark that is defying the law of gravitation by moving upward over the trunk, and as he flies off to another tree he resembles a little dry leaf blown about by the wind.”Tyler 1948a: 56

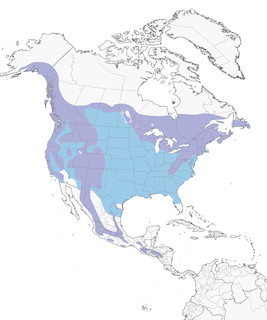

One of the continent's most inconspicuous songbirds, the Brown Creeper is the only treecreeper in North America. Its cryptic coloration and high-pitched vocalizations make it difficult to detect, yet it is widely distributed in coniferous, mixed, and deciduous forests throughout North America, from Alaska and Canada south to northern Nicaragua. In its endless pursuit of bark-dwelling invertebrates, it begins at the base of a tree trunk, climbs upward, sometimes spiralling around the trunk until it nears the top, then flies to the base of a nearby tree to begin the process again. This creeper uses its slender, decurved bill to glean invertebrates—mainly insects, spiders, and pseudoscorpions—from furrows in the bark. It was not until 1879 that naturalists discovered its unique habit of building its hammock-like nest behind a loosened flap of bark on a dead or dying tree.

The sole representative of its family in North America, the Brown Creeper is almost indistinguishable from its Old World counterpart, the Eurasian Treecreeper (Certhia familiaris), and they were long considered conspecific. In the last decade, the systematics of treecreepers were investigated using vocalizations, morphological traits, and molecular data. These studies have confirmed that Brown Creeper and Eurasian Treecreeper should be treated as separate species.

Although the Brown Creeper is found in a variety of forest habitats, it favors forest stands with an abundance of dead or dying trees for nesting and large live trees for foraging. It is most abundant in mature and old forests in summer but uses a wider variety of wooded habitats in winter. In recent decades, its numbers have increased in northern hardwood forests, possibly as a result of reforestation and the widespread mortality of trees due to gypsy-moths (Lymantria dispar) and other alien insect pests. Its breeding range appears to be expanding in mid-Atlantic states, the Midwest, Georgia, and California, although local extirpations are known due to habitat loss in New York, Michigan, and the lower Colorado River Valley. This creeper is often considered a year-round resident throughout its breeding range, but northern and high-altitude populations migrate. It is territorial during the breeding season, but in winter often joins mixed-species foraging flocks and roosts communally with other Brown Creepers.

Populations of this species have declined since presettlement times in northwestern Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) forests owing to loss of mature and old-growth trees (Raphael et al. 1988), and in southwestern ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa; Brawn and Balda 1988b) owing to loss of mature pines. Current population-trend information indicates the species is stable in most areas in North America. North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) trend data, however, should be viewed with caution owing to the low number of individuals counted on routes and biases associated with roadside surveys. It is highly likely that creeper numbers have continued to decline in the West as a result of timber-harvesting practices. Degradation of habitat via the harvesting of large, live trees, salvage-logging practices that remove dead or dying trees, and the increasing fragmentation of forests, particularly in western North America, are the greatest known threats to current populations. Loss of large trees to exotic insects and diseases and the eventual loss of large snags in eastern forests could also affect creepers negatively. Partners in Flight groups are concerned about Brown Creepers in Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Montana, and the southern Blue Ridge and Sierra Nevada because of the negative effects of logging and forest fragmentation and the association of this species with large trees and a rare community type.

Despite the Brown Creeper's widespread distribution, more research is needed on almost every aspect of its biology, especially for Mexican and Central American populations. Key studies of this species include a comprehensive nesting study (Davis 1978a), geographic variation in song (Baptista and Johnson 1982, Tietze et al. 2008), song analysis and taxonomic relationships (Baptista and Krebs 2000), systematics (Webster 1986, Unitt and Rea 1997, Tietze et al. 2006, Manthey et al. 2011a,b), foraging ecology (Franzreb 1985, Morrison et al. 1987, Lundquist and Manuwal 1990, Weikel and Hayes 1999), and habitat use and requirements (Raphael and White 1984, Mariani 1987, Siegel 1989, Mariani and Manuwal 1990, Keller and Anderson 1992, Adams and Morrison 1993, Freemark et al. 1995, Hejl et al. 1995, Poulin et al. 2008).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding