Venezuelan Flowerpiercer Diglossa venezuelensis Scientific name definitions

- EN Endangered

- Names (19)

- Monotypic

Text last updated July 15, 2015

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Catalan | punxaflors de Veneçuela |

| Dutch | Rouwberghoningkruiper |

| English | Venezuelan Flowerpiercer |

| English (United States) | Venezuelan Flowerpiercer |

| French | Percefleur du Venezuela |

| French (France) | Percefleur du Venezuela |

| German | Dunkelhakenschnabel |

| Japanese | ミヤマハナサシミツドリ |

| Norwegian | venezuelablomsterborer |

| Polish | haczykodziobek wenezuelski |

| Russian | Траурный цветокол |

| Serbian | Venecuelanska bušilica |

| Slovak | kvetárik tmavý |

| Spanish | Pinchaflor Venezolano |

| Spanish (Spain) | Pinchaflor venezolano |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Robanéctar Negro |

| Swedish | venezuelablomstickare |

| Turkish | Venezüela Çiçekdeleni |

| Ukrainian | Квіткокол венесуельський |

Diglossa venezuelensis Chapman, 1925

Definitions

- DIGLOSSA

- venezuelae / venezuelana / venezuelanus / venezuelense / venezuelensis

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

The male Venezuelan Flowerpiercer is basically black with a small white tuft on the flanks, whilst the female is olive-brown above with a yellowish-olive head and buffy-brown underparts. Considered to be globally Endangered given an incredible paucity of modern records, despite having been common in the first part of the 20th century, the Venezuelan Flowerpiercer is endemic to the northeast corner of the country. It inhabits montane, evergreen forest edge, secondary forest, and second-growth scrub, at elevations of 1525–2450 m on the Cordillera de Caripe, and lower altitudes on the nearby Paria Peninsula. Some authorities have speculated that the species might perform seasonal movements, and it is also possible that the Venezuelan Flowerpiercer possesses some highly specialist microhabitat requirement, yet to be determined.

Field Identification

Systematics History

Subspecies

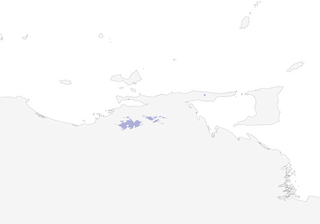

Distribution

NE Venezuela: Cordillera de Caripe, in N Sucre (from E slope of Cerro Peonía E to Cerro Turumiquire, on Monagas border); also slopes of Cerro Negro (on Sucre–Monagas border), and Cerro Humo (Paria Peninsula).

Habitat

Borders of humid montane forest, also young to older second growth and shrubby and bushy areas adjacent to forest. At 1525–2450 m in Turimiquire Massif; 1675–1775 m on Cerro Negro; sightings down to 885 m at Melenas, on Paria Peninsula.

Movement

Diet and Foraging

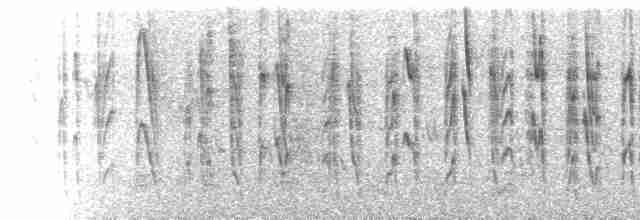

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Breeding

Conservation Status

ENDANGERED. Restricted-range species: present in Caripe-Paria Region EBA. Very local; declining. Known only from a small number of localities in Turimiquire Massif and Paria Peninsula in extreme NE Venezuela. A fairly large number of specimens were taken from Cerro Turimiquire as recently as 1963, but the number of sightings since that time is small. Two six-week ornithological expeditions to the Paria Peninsula (Cerro Humo, 1994 (1), and Cerro El Olvido, 1988 (2) ) during wet season failed to find the species. Recent sightings (post-2000), involving only a handful of birds, come from only three localities: Quiriquire ("Piedra 'e Mole'") in Serranía de Turimiquire, Cerro Negro in Cordillera de Caripe and Cerro Humo in Paria Peninsula. Known to occur in Paria Peninsula (IUCN Cat. II; 375 km2) and El Guácharo (IUCN Cat. II; 627 km2) National Parks. However, legal enforcement and management are lacking in both parks; for example, in Paria Peninsula, there are only two or three park guards, no vehicles or boats, a minimal budget and little political support (3, 4). Widespread deforestation for agriculture and cattle pastures evident in Cordillera de Caripe, and extensive forest damage taking place even in El Guácharo National Park. Most of Cerro Negro (within park boundaries) now completely denuded or devoted to shade coffee plantations. In Serranía de Turimiquire, deforestation for coffee, bananas, mango and citrus is occurring, although considerable intact forest still present; largest remaining forest block (Piedra 'e Mole') measures c. 80 km2 (5). Cerro Humo faces similar forest degradation and uncontrolled burning. Use of home-made shotguns by adult hunters and catapults by children is widespread and common in Paria Peninsula. Extent to which this species is able to survive in areas of regrowth vegetation or in coffee plantations, which increasingly threaten to overwhelm almost all of the native forest remaining in its range, is not known. Other members of its genus tend to thrive, or at least survive, in cultivated areas and gardens with flowers, even in settled areas, but that seems not to be the case with present species and an assessment of its habitat requirements is needed urgently. A recent paved road from Güiria to tip of Paria Peninsula (at Macuro) will almost certainly lead to loss of habitat as human settlement follows. A proposed gas pipeline over Paria Peninsula, running from gas fields on N shore to cryogenics facilities on S shore, represents an additional serious threat (3, 4). Considered Endangered at the national level in Venezuela (6).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding