Baikal Teal Sibirionetta formosa Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (39)

- Monotypic

Text last updated July 29, 2016

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Asturian | Zarceta del Baikal |

| Bulgarian | Байкалско бърне |

| Catalan | xarxet del Baikal |

| Chinese | 巴鴨 |

| Chinese (Hong Kong SAR China) | 花臉鴨 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 花脸鸭 |

| Croatian | šarenoglava patka |

| Czech | čírka sibiřská |

| Danish | Sibirisk Krikand |

| Dutch | Siberische Taling |

| English | Baikal Teal |

| English (United States) | Baikal Teal |

| Finnish | siperiantavi |

| French | Sarcelle élégante |

| French (France) | Sarcelle élégante |

| German | Gluckente |

| Greek | Σαρσέλα της Βαϊκάλης |

| Hebrew | שרשיר סיבירי |

| Hungarian | Cifra réce |

| Icelandic | Kvakönd |

| Italian | Alzavola asiatica |

| Japanese | トモエガモ |

| Korean | 가창오리 |

| Lithuanian | Baikalinė kryklė |

| Mongolian | Байгалийн нугас |

| Norwegian | gulkinnand |

| Polish | bajkałówka |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Marrequinha-formosa |

| Romanian | Rață mică de Baikal |

| Russian | Клоктун |

| Serbian | Sibirska krdža |

| Slovak | kačica pestrá |

| Slovenian | Formoški kreheljc |

| Spanish | Cerceta del Baikal |

| Spanish (Spain) | Cerceta del Baikal |

| Swedish | gulkindad kricka |

| Thai | เป็ดเปียหน้าเหลือง |

| Turkish | Sarı Yanaklı Ördek |

| Ukrainian | Чирянка-квоктун |

Sibirionetta formosa (Georgi, 1775)

Definitions

- SIBIRIONETTA

- formosa

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

39–43 cm; male 360–520 g, female 402–505 g (1); wingspan 65–75 cm (2). Slightly larger than Anas crecca, with proportionately longer wings and tail, and all plumages share distinctive wing-pattern and entirely dark grey (and quite narrow) bill. Male unmistakable , with white supercilium reaching nape, curving black line from eye to throat, dull brown upperparts with long, rufous and white-fringed scapulars , pinkish breast , vertical white breast-stripe and grey flanks, dark grey bill, grey to yellowish legs and feet, and brown eyes; has eclipse plumage, which is very similar to that of adult female, but richer rufous and often retains dark line from eye to throat . Female differentiated from other teals by round whitish mark behind bill, encircled by dark border, with dark eyestripe , warm breast and often has dark and pale marks on lower cheeks; female Spatula querquedula lacks round, white loral spot and has unbroken supercilium. Juvenile resembles female with less well-defined facial pattern, and has underparts spotted or streaked brown, lacking rufous tones, and male may have paler base to bill.

Systematics History

Subspecies

Hybridization

Hybrid Records and Media Contributed to eBird

-

Baikal Teal x Falcated Duck (hybrid) Sibirionetta formosa x Mareca falcata

-

Baikal Teal x Northern Pintail (hybrid) Sibirionetta formosa x Anas acuta

-

Baikal x Green-winged Teal (hybrid) Sibirionetta formosa x Anas crecca

Distribution

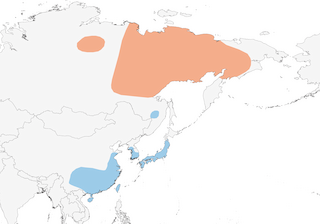

E Siberia from Yenisey Valley E to Kamchatka and Sea of Okhotsk coast. Winters mainly in Japan, South Korea and mainland China; rare winter visitor to Taiwan and Hong Kong.

Habitat

Rivers, small lakes, pools and marshes in well-wooded country or in Arctic tundra. Winters in freshwater or brackish wetlands, floodplains, rice fields (3) and meadows. Mainly in lowlands, but recorded to at least 2650 m in winter (4).

Movement

Migratory: winters (mainly between mid Nov to late Feb or early Mar) (1) in E & SE China (S to Guandong and Yunnan), South Korea and S Japan (mainly on Honshu ) (4), although arrives in Korea as early as mid Sept (1) and recorded on Hokkaido (N Japan) and in NE China (Heilongjiang) as late as May and Jun, respectively (4); rarely winters S to Taiwan (5), Hainan (6) and Hong Kong, with a few individuals (probably vagrants) venturing as far W as Pakistan (seemingly none recent) (4), N & NE India (mainly Bihar, West Bengal and Assam, but also S to Gujarat) (4), Nepal (Oct 1984, Feb 1987, Feb 1989) (4) and Bangladesh (Jan 1995, Feb 2001, Feb 2011, Dec 2012, Feb 2013) (7, 8), but also recorded in Myanmar (Jan–Feb 2000), Thailand (Feb 1990, Jan 1992, Jan–Feb 2000) (4) and Philippines (Jan–Feb 2016) (9), as well as in SW Russia (Tomsk, Baraba steppe) (10). Migrates mainly through middle and lower Amur Valley in autumn, rather than via coast, thus very few records on Hebei (NE China) coast at this season (dated 25 Aug–16 Sept) (11), while in spring huge numbers (up to 86,000) have been observed at L Khanka on China/Russia border and in Daubikhe Valley (1), and species was formerly common at this season through L Baikal region (30 Apr–3 Jun; in autumn, 19 Aug–29 Sept) (12). Recorded in NE China (Inner Mongolia) as early as Jul (4). Routes of birds wintering in Japan recently studied using satellite telemetry; four teals were captured in winter and, in spring, they crossed the Sea of Japan in late Mar and used stopovers on Khanka Plain and Three Rivers Plain for c. 1 month, arriving at their breeding sites in Sakha Republic, Russia, in early Jun, and commencing autumn migration in early Sept, moving S via the same route as far as Three Rivers Plain, but thereafter moving to W South Korea for several weeks, before one finally returned to the same site as they were captured in Japan, in Jan (13). Vagrants have been reported from W Europe (as far as Britain and Spain) (14) and North America (chiefly Pacific coast, between Aleutians and California , in autumn, occasionally in winter and spring and inland to Arizona) (15), but probably at least some of these have involved escapes from captivity (species was first introduced to Europe c. 1840) (10). However, in Europe, recent records in Essex (male, Jan 1906) and Suffolk, E England (first-winter male, Nov 2001) (16) and Denmark (first-winter, Nov 2005) (17) have been accepted as involving wild birds following stable isotope analysis (18, 19); nine other British records are considered unacceptable as wild birds or otherwise unproven (20). European records also available from Spitsbergen, Ireland (Jan 1967), France (17–22 records, including five in Nov 1836), Belgium (14–15 records), Netherlands (nine records generally considered to be of wild birds) (21), Germany (1910), Switzerland (Mar 1992), Norway (Mar–Apr 1979), Sweden (nine records, all considered to be escapees), Finland (Nov 1950), Poland (two records), Italy (nine records) and Malta (Apr 1912) (10, 22).

Diet and Foraging

Seeds, leaves, stems and other vegetative parts of grasses, sedges, aquatic plants and crops (e.g. rice in winter) (1); also aquatic invertebrates (molluscs, insects). Stomach contents in South Korea and Russia comprised split rice, soybeans, grains of Echinochloa orizoides, seeds of wild cereals and herbs such as Panicum grus-galli, Trifolium and Polygonum aviculare (1). On migration in Russia feeds on seeds of Ruppia and Zostera, but on breeding grounds switches to feeding on horsetails, fresh grass leaves and some invertebrates, while prior to autumn migration the birds took sedge seeds and invertebrates; at L Khanka, on stopover prior to arriving on wintering grounds, seeds of hydrophilic plants were important (Panicum grus-galli, Trifolium, Digitaria linearis, Viola, Polygonum and Setaria) (4). In Japan, birds may roost up to 10 km from foraging sites (4). Feeds by dabbling from water surface, head dipping and upending; also on foot , looking for acorns in woods and even for grain and seeds on roads at night. Extremely active while foraging, moving in large groups of up to 1000 birds, which may remain in one area for as short a period as 20 minutes (4). Highly nocturnal on wintering grounds, being largely inactive during daytime but becoming more active in late afternoon (4, 22).

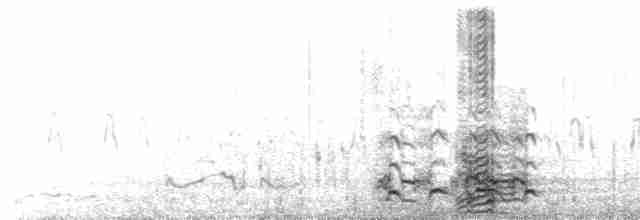

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Occasionally in autumn, but more frequently in spring, males incessantly produce deep, chuckling “wot-wot-wot” (sometimes given in flight) and “ruk-ruk” in display, while females utter low “quack” or “kweck”, and a soft, repeated “geg-geg-geg” when encouraging male to copulate, while female’s “Decrescendo” call is only infrequently given and comprises long note followed by c. 5 shorter, descending ones; species is often rather quiet in midwinter, but large flocks emit low, rumbling noise, reminiscent of distant, busy roadway, audible up to 500 m away if weather still (1).

Breeding

Poorly known. Arrives on breeding grounds between late Apr and May, with egg laying in late May S of Arctic Circle or early–mid Jun in forest-tundra zone, with eggs hatching third week of Jun in Yakutia and young fledging first week of Aug (1). In single pairs or loose groups; nests on ground, concealed among vegetation including willow bushes (4), usually near water. Clutch 4–10 pale greyish-green eggs, size 45–52·5 mm × 32–38 g, mass c. 31 g (1); incubation c. 24–25 days (captivity) by female alone (1); chicks have dark brown down above, yellow below, cared for by female alone (1); fledging period unknown (1). Sexual maturity probably achieved at one year (1).

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern), but until recently treated as Vulnerable by BirdLife International. CITES II. Protected in Russia, Mongolia, Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong and some provinces in China; listed in Red Data books of South Korea, Russia and Yakutia, while some important sites are protected, including L Bolob and L Khanka (Russia), Geum R (South Korea) and Katano (Japan). Population currently considered to be increasing following decades of decline, with just 20,000–40,000 thought to survive in 1980s (1). Supporting view that genuine population increase has taken place in South Korea (rather than shift in main wintering grounds), analysis of counts at 38 sites annually since 1999 indicate increase from a yearly average of 11,533 in 1999–2003 to 314,994 in 2005–2009, and this is believed to be linked to the availabilty of newly reclaimed land as well as a decline in hunting. Formerly considered commonest duck in NE Asia, but declined markedly due to overhunting (e.g. 50,000 taken by just three men over 20 days in Japan in 1947) (1), pollution, pesticide use (especially in Russia) (1) and habitat destruction (principally for agricultural development); after 1908 thousands were imported to Europe from China, and imports continued until at least the 1980s (22). Previously widely distributed in Japan where it was common to abundant winter visitor, with flocks of 100,000 near Osaka; now only uncommon winter visitor, with fewer than 10,000 birds in whole of Japan by 1980, only c. 2000 in late 1980s and just c. 700 during mid 1990s (1). In China, locally abundant in Yangtze Valley and Fujian in early 20th century, but numbers wintering in first-named region now c. 20,000 at most (1), with just 28 counted in this region in early 2004 (23); however, 27,000 at Nansi Hu in late 1980s (24), in Jan 2006 flock of 8000–10,000 birds at Chongming Dongtan National Nature Reserve, Shanghai (25) and in 2006/07 a flock of 50,000 was at Yancheng National Nature Reserve, with result that national population estimate is currently 91,000. However, largest modern-day counts are from South Korea, where numbers have risen from 18,000 individuals in winter 1991, to 210,000 in 1999, 300,000–400,000 in winter 2001/02 and > 400,000 in 2002–2003 (including single flock of c. 400,000 in Nov 2003) (1), while, more recently, these totals have been eclipsed by 658,000 during surveys in 2004, including c. 600,000 on lower Geum R, and c. 1,060,000 in Jan 2009, with concentrations of > 20,000 at six different sites. Habit of forming dense aggregations in winter renders species susceptible to infectious diseases; 10,000 birds were found dead owing to avian cholera in Oct 2002 (1). Part of decline in 1960s and 1970s can be attributed to changes in breeding grounds, with westernmost part of range (Ob, Yenisey and Taz drainages) apparently now largely abandoned (1), and almost no recent records in Buryatia (26).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding