Black-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus erythropthalmus Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (45)

- Monotypic

Text last updated April 13, 2018

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Bulgarian | Черноклюна кукувица |

| Catalan | cucut becnegre |

| Croatian | crnokljuna kukavica |

| Czech | kukačka černozobá |

| Danish | Sortnæbbet Gøg |

| Dutch | Zwartsnavelkoekoek |

| English | Black-billed Cuckoo |

| English (United States) | Black-billed Cuckoo |

| French | Coulicou à bec noir |

| French (France) | Coulicou à bec noir |

| German | Schwarzschnabelkuckuck |

| Greek | Μαυρόραμφος Κούκος |

| Haitian Creole (Haiti) | Ti Tako bèk nwa |

| Hebrew | קוקיה שחורת-מקור |

| Hungarian | Feketecsőrű esőkakukk |

| Icelandic | Regngaukur |

| Italian | Cuculo occhirossi |

| Japanese | ハシグロカッコウ |

| Lithuanian | Raudonakė amerikinė gegutė |

| Norwegian | svartnebbgjøk |

| Polish | kukawik czarnodzioby |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | papa-lagarta-de-bico-preto |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Papa-lagarta-de-bico-preto |

| Romanian | Cuc cu cioc negru |

| Russian | Черноклювая пиайя |

| Serbian | Crnokljuna američka kukavica |

| Slovak | kukavka čiernozobá |

| Slovenian | Črnokljuni kukavec |

| Spanish | Cuclillo Piquinegro |

| Spanish (Argentina) | Cuclillo Ojo Colorado |

| Spanish (Costa Rica) | Cuclillo Piquinegro |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Primavera de pico negro |

| Spanish (Dominican Republic) | Pájaro Bobo Pico Negro |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Cuclillo Piquinegro |

| Spanish (Honduras) | Cuclillo Pico Negro |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Cuclillo Pico Negro |

| Spanish (Panama) | Cuclillo Piquinegro |

| Spanish (Paraguay) | Cuclillo ojo colorado |

| Spanish (Peru) | Cuclillo de Pico Negro |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Pájaro Bobo Piquinegro |

| Spanish (Spain) | Cuclillo piquinegro |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Cuclillo Pico Negro |

| Swedish | svartnäbbad regngök |

| Turkish | Kara Kuyruklu Guguk |

| Ukrainian | Кукліло чорнодзьобий |

Coccyzus erythropthalmus (Wilson, 1811)

Definitions

- COCCYZUS

- erythropthalma / erythropthalmos / erythropthalmus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

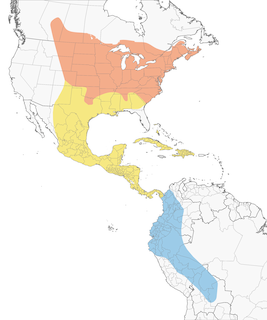

Graceful in flight but skulky and retiring in habit, the Black-billed Cuckoo is among North America's most elusive birds. It is frequently confused with the more common Yellow-billed Cuckoo (Coccyzus americanus), with which it shares similarities in plumage, behavior, and vocalizations. Although both species occur sympatrically through much of their ranges, the Black-billed Cuckoo has the more northerly distribution. In addition, Black-billed Cuckoo is more closely associated with densely wooded habitat and occurs more frequently within coniferous vegetation.

The Black-billed Cuckoo is rarely seen during migration and on overwintering grounds in South America due to its silent and secretive manner. As a result, its nonbreeding distribution remains poorly defined. In North America, it is among the later migrants to return each spring; arrival on breeding grounds is announced by its staccato, repetitive call— cu-cu-cu cu-cu-cu —uttered as individuals fly overhead on late spring evenings. Vocal night flights increase as breeding commences. These flights, in concert with its quiet, sluggish behavior during the day, have led some ornithologists in the past to suggest that the Black-billed Cuckoo is partially nocturnal in summer.

Like other cuckoos, the Black-billed Cuckoo exhibits unusual breeding behavior. The onset of nesting is apparently correlated with insect outbreaks, particularly those of caterpillars and cicadas. Furthermore, localized food abundance has been linked to increased clutch size and nesting success and to the frequency of brood parasitism. The young are robust among altricial birds. Shiny, black nestlings hatch following a brief 11-day incubation period. Within 3 hours of hatching, they can raise themselves onto twigs, using their feet and bills. They mature rapidly, and at 6 days of age resemble porcupines, with their long, pointed feather sheaths. Just prior to the young leaving the nest on the following day, the sheaths burst and the chick becomes fully feathered, a process once likened to the commotion in a corn popper. The agile, young cuckoos are capable of hopping and climbing rapidly through the vegetation. When threatened, they assume a bizarre defensive posture—necks outstretched, bills pointed straight up, eyes wide open—that resembles the erect pose employed by American Bittern (Botaurus lentiginosus) chicks.

The Black-billed Cuckoo is a notorious consumer of caterpillars, with a demonstrated preference for noxious species, including the Eastern Tent Caterpillar (Malacosoma americanum), Fall Webworm (Hyphantria cunea), and larvae of Lymantria dispar. Observations of individuals consuming 10–15 caterpillars per minute are testimony to the great service this species provides in forests, farms, and orchards. Stomach contents of individual cuckoos may contain more than 100 large caterpillars or several hundred of the smaller species. The bristly spines of hairy caterpillars pierce the cuckoo's stomach lining giving it a furry coating. When the mass obstructs digestion, the entire stomach lining is sloughed off and is regurgitated as a pellet.

The Black-billed Cuckoo was formerly much more common in North America. Populations have declined across its range throughout the twentieth century, with particularly severe decreases in the 1980s and 1990s. Accounts from naturalists in the late 1800s speak of flocks of cuckoos descending on caterpillar-laden trees and not departing until every insect was consumed. Caterpillar irruptions still occur, but since they have been controlled by pesticide use, cuckoos are rarely seen more than singly. It is likely that pesticides, and the concomitant reduction of prey availability, have caused Black-billed Cuckoo mortality and reduced breeding success, but these effects have never been quantified.

Few aspects of Black-billed Cuckoo life history have been adequately studied. Typical breeding and nestling behavior has been described by Spencer (1) and Sealy (2). In addition, some anomalous breeding behaviors, such as brood parasitism and resource-dependent clutch sizes, have been examined by Nolan and Thompson (3), Sealy (4, 5) and Stewart (6). Many workers have observed an association between local cuckoo abundance and insect irruptions (e.g., 7, 8, 9, 10), and detailed examinations of stomach contents have been made (11, 12, 13). However, no comprehensive studies of the effects of resource availability on Black-billed Cuckoo abundance, distribution, or fecundity have been performed.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding