Chinstrap Penguin Pygoscelis antarcticus Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (25)

- Monotypic

Text last updated August 30, 2013

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Bulgarian | Антарктически пингвин |

| Catalan | pingüí carablanc |

| Croatian | ogrličasti pingvin |

| Czech | tučňák uzdičkový |

| Dutch | Stormbandpinguïn |

| English | Chinstrap Penguin |

| English (United States) | Chinstrap Penguin |

| Finnish | myssypingviini |

| French | Manchot à jugulaire |

| French (France) | Manchot à jugulaire |

| German | Kehlstreifpinguin |

| Icelandic | Hettumörgæs |

| Japanese | ヒゲペンギン |

| Norwegian | ringpingvin |

| Polish | pingwin maskowy |

| Russian | Антарктический пингвин |

| Serbian | Ogrličasti pingvin |

| Slovak | tučniak čiapočkatý |

| Spanish | Pingüino Barbijo |

| Spanish (Argentina) | Pingüino de Barbijo |

| Spanish (Chile) | Pingüino antártico |

| Spanish (Spain) | Pingüino barbijo |

| Swedish | hakremspingvin |

| Turkish | Çember Sakallı Penguen |

| Ukrainian | Пінгвін антарктичний |

Pygoscelis antarcticus (Forster, 1781)

Definitions

- PYGOSCELIS

- antarctica / antarcticum / antarcticus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

The Chinstrap Penguin is a circumpolar species that breeds on widely dispersed islands throughout the sub-Antarctic. The highest concentration of these breeding localities is the South Atlantic where the species breeds on the South Georgia, South Orkney, South Shetland, and South Sandwich Islands. Due to a recent population explosion of krill, the Chinstraps’ main food source, the Chinstrap is fast becoming one of the most numerous penguin species, second only to Macaroni Penguin. From mainland South America, this species is most easily seen off the coast of southern Argentina and Tierra del Fuego where it occurs in the Austral winter. The Chinstrap Penguin is best identified by its white face and black bill rather than the chinstrap, which is potentially difficult to see in the field.

Field Identification

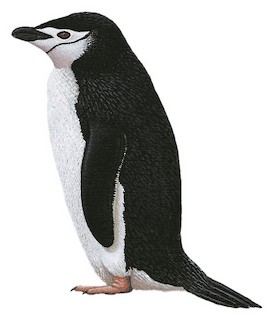

68–77 cm; 3·2–5·3 kg. Long-tailed penguin with largely white face . Adult has entirely black or bluish-black top of head and upperparts , this colour as a wedge down side of breast just before axillary area; flipper black above with narrow white trailing edge (except at tip), white to pinkish below with black tip and narrow, often incomplete blackish leading edge; tail black; face from lores and superciliary area to side of upper neck and entire underparts white, except for narrow black line running from side of rear crown through ear-coverts and across chin; iris orange-brown to dark brown, narrow orbital ring of bare black skin; bill black; legs pink, blackish soles and rear of tarsus. Some albinos and leucistic individuals have been reported. Sexes alike. Juvenile has smaller bill than that of adult, also tiny dark streaks on foreface, especially around eye, and iris duller.

Systematics History

Subspecies

Distribution

Circumpolar in S, with bulk of population in S Atlantic.

Habitat

Marine, mostly in zones with light pack ice (10–30% ice cover). Nests on irregular rocky coasts , in ice-free areas. Inshore feeder . An ice-intolerant species , whose breeding range has shown southward expansion in recent decades (1).

Movement

Dispersive, wintering in zones of pack ice from Apr/May to Oct/Nov. Two of six satellite-tracked individuals from Admiralty Bay (South Shetlands) colony migrated to region of South Orkneys and South Sandwich Is, moving 800 km and 1300 km, respectively (2). Yearlings return to natal colony around Jan, remaining until Mar. In Jan–Feb 2008, a pre-moulting adult migrated from Bouvet I (a small, relatively recently established colony) to South Sandwich Is (large, well-established colonies), the c. 3600-km journey taking c. 3 weeks, and arrival time consistent with moult timing; the bird did not follow shortest route, but, instead, followed what appeared to be a sequence of two or three rhumb lines of constant bearing (minor deviations to S and N of general path were consistent with local water currents); travel speed was greatest during daylight and decreased at night, suggesting that the penguin rested or fed opportunistically mostly at night; although long-range winter movements to feeding areas in proximity of distant colonies are known, this appears to be first observation of such a movement during period between breeding and moulting (and first record of an individual arriving at such a distant colony) (3). Accidental in Australia and at Macquarie I, Crozets and Gough I; vagrant to Falkland Is (4) and adjacent Argentine coast (N to Buenos Aires).

Diet and Foraging

Almost exclusively Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba), normally in 4·0–5·6-cm size range; also takes other species of crustacean and a few fish. Apparently captures prey by means of pursuit-diving; maximum depth of dives 70 m, but most to less than 45 m, and c. 40% to less than 10 m. Satellite-tracking of individuals from two breeding colonies in South Shetland Is during austral winters revealed that the birds foraged mostly inshore (on shelf) N of South Shetlands in 2000, but mainly offshore in pelagic waters in 2004, pre-winter analyses suggesting that prey more abundant inshore in summer 2000 than in 2004 (2). One study found that Chinstraps feed mainly at night, foraging most effectively at depths of 15–60 m, in contrast to P. adeliae, which foraged mainly in the afternoons in surface waters down to 15 m, and P. papua, which foraged mainly in the mornings at depths below 60 m; the possibility that their krill prey moves vertically means that this vertical and temporal ecological partitioning does not necessarily indicate reduced competition between the three species (5).

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Noisy at colony. In display, a loud cackling (with bill open) , also a repeated “ah, kauk kauk kauk” with head up and with head-swinging and flipper-beating; also a soft humming; also a hissing sound lasting for c. 1·5 seconds, both during bowing display and during agonistic encounters. Contact call a low bark.

Breeding

Arrival at colony Oct–Nov, earliest laying Nov/Dec. Colonial, typically in huge colonies of hundreds of thousands of birds; often nests beside congeners. Nest a very simple round platform of stones. Clutch two eggs, rarely one or three; incubation by both sexes, period 31–40 days, with single stints of 1–18 days; first down pale grey , often palest on head , second down brownish grey above and on head down to below eye and to mid-throat, with ear-coverts to lower throat and underparts paler dirty creamy white; chicks form crèche at 23–29 days; fledging 48–60 days. Overall breeding success 0·36 chicks per pair (18·7%) in South Orkney Is, 1·06 chicks per pair in South Shetland Is; very wide annual variation throughout range. Sexual maturity reached at three years of age. Chinstrap Penguins dominate P. adeliae where the two nest together and often displace P. adeliae from their nest-sites (6).

In study of Vapour Col colony on Deception I (South Shetlands) in 2002–2003 season, isolated subcolonies and subcolonies on slopes were found to be smaller and occupied by males having either shorter bill (former) or less deep bill (latter); isolated subcolonies had delayed hatching date and lower hatching success, and females at more sloping subcolonies laid smaller eggs; results indicated that physical characteristics of subcolonies (degree of isolation and slope), rather than size alone, affect breeding success of this species (7). On Deception Island, Penguins breeding in the centre of subcolonies hatch their eggs significantly earlier and have larger broods and than those nesting near or at the edge of the subcolonies. These differences are highly significant in colder years, when peripheral nests produce fewer young. It has been shown that penguins breeding at the edge of subcolonies lose heat twice as rapidly as those breeding in the interior of the subcolony. In a re-occupation experiment, evacuated central nests were re-occupied almost ten times as rapidly as edge nests. Subcolonies tend to be as circular as possible, thus reducing the proportion of edge nests (8).

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). Locally abundant. Global population estimated currently to number minimum of 8,000,000 individuals. Although data not always easy to interpret, and despite apparent increases noted at some localities, this species has declined significantly since 1980s; at two sites on King George I, large decreases recorded in 1990–1996 (9), and censuses at King George during 2002–2004 revealed an overall decline of 57% since 1979, similar to a general trend in other parts of Antarctic Peninsula region (10, 11). Recent censuses on Deception Island confirm continuing decline in some parts of Antarctic Peninsula (12). Following apparently marked earlier increase, with expansion of range, total population in 1980s was estimated at 6,500,000–7,500,000 pairs, of which c. 5,000,000 in South Sandwich Is, with higher numbers also at traditional colonies of South Georgia, Cooper Bay and Ice Fjord; increase apparently related to population explosion of krill. A subsequent increase in intensity and extent of commercial fishing in this penguin’s foraging waters may have had opposite effect. Although majority of this species inhabit Scotia Arc, a very tiny population has been reported on several occasions from Chinstrap Islet, in Balleny Is, 5000 km away on opposite side of Antarctica: aerial photographic census in Dec 2000 indicated that total penguin numbers at Balleny Is had declined by 8% since previous census, in 1984, while combined populations of the two largest colonies (Chinstrap Islet and Sabrina Islet) had grown by 11%; a visit on foot confirmed for first time that present species also breeds on Sabrina Islet, with 20–24 nests on margins of P. adeliae colony (colony totalled 3790 pairs in all); small size and anomalous location of Balleny population of present species merit further study, and stringent protection is recommended (13).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding