Dark-eyed Junco Junco hyemalis Scientific name definitions

Text last updated January 1, 2002

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Catalan | junco fosc |

| Croatian | sivoglavi strnadar |

| Czech | strnadec zimní |

| Danish | Mørkøjet Junco |

| Dutch | Grijze Junco |

| English | Dark-eyed Junco |

| English (United States) | Dark-eyed Junco |

| French | Junco ardoisé |

| French (France) | Junco ardoisé |

| German | Winterammer |

| Greek | Μολυβοτσίχλονο |

| Hebrew | יונקו כהה-עין |

| Hungarian | Füstös junkó |

| Icelandic | Vetrartittlingur |

| Japanese | ユキヒメドリ |

| Lithuanian | Pilkasis junkas |

| Norwegian | vinterjunko |

| Polish | junko |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Junco |

| Romanian | Iunco cu ochi negri |

| Russian | Серый юнко |

| Serbian | Tamnooki junko |

| Slovak | strnádlik sivý |

| Slovenian | Sivi junko |

| Spanish | Junco Ojioscuro |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Junco de ojos pardos |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Junco Ojos Negros |

| Spanish (Panama) | Junco Ojioscuro |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Junco Ojioscuro |

| Spanish (Spain) | Junco ojioscuro |

| Swedish | mörkögd junco |

| Turkish | Kara Gözlü Junko |

| Ukrainian | Юнко сірий |

Junco hyemalis (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- JUNCO

- junco

- hyemalis

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

The Dark-eyed Junco, one of the most common and familiar North American passerines, occurs across the continent from northern Alaska south to northern Mexico. It is familiar because of its ubiquity, abundance, tameness, and conspicuous ground-foraging winter flocks, which are often found in suburbs (especially at feeders), at edges of parks and similar landscaped areas, around farms, and along rural roadsides and stream edges. Audubon (Audubon 1831: 72) stated that “there is not an individual in the Union who does not know the little Snow-bird,” and to some people “snowbird” is the junco's name today. Its plumage is characterized by white outer tail feathers that flash when the bird takes flight and by a gray or blackish “hood” (head, nape, throat) and dark back that contrast with its whitish breast and belly. A recent estimate set the junco's total population at approximately 630 million (Folkard and Smith 1995).

The species is important in ecological research, both theoretical and applied. Theoreticians testing hypotheses such as those concerning resource use, habitat partitioning, and community structure regularly rely on junco data, and conservation biologists and forest managers turn to junco populations to evaluate methods and predictions. The additional attributes of ease of cap-ture and tolerance of experimental manipulation have made the bird a model species in physiological, behavioral, and neurological research. Most notably, Rowan's (Rowan 1925, Rowan 1927a, Rowan 1928) pioneer studies, begun in 1924, of the role of day length in gonadal recrudescence and migratory behavior focused on the gonadal responses of juncos that were simultaneously exposed to Canadian winter weather and spring (artificially prolonged) photoperiods. This work initiated many decades of research that has contributed greatly to our understanding of the avian annual cycle. Other areas of fruitful experimental study have been neurobiology of song, social structure and dominance, anti-predation behavior, brain and associated functions, migration and winter distribution, fitness effects of hormonal manipulation, winter physiology, and population biology.

As its distribution and varied breeding habitats would predict, junco populations differ in plumage and bill color, migratory behavior, and body size. This variation is responsible for a “turbulent” taxonomic history (Thatcher 1965) and a reputation as a “nightmare” for systematists (Mayr 1942). Miller (Miller 1941b), working without modern methods of studying phylogeny and speciation, thoroughly revised the genus in 1941; his classification has since been modified, but his treatise remains important, particularly on the subject of geographic variation.

Until the 1970s, the currently recognized Dark-eyed Junco was split into 5 distinct species, 3 of them comprising 2 or more subspecies. The American Ornithologists' Union (1973, American Ornithologists' Union 1982) lumped these 5 species but acknowledged the distinctiveness of the former species by designating them and their subspecies as informal “groups” of Junco hyemalis . Each group bears the scientific and vernacular name that it previously bore as a species: hyemalis (Slate-colored Junco); aikeni (White-winged Junco); oreganus (Oregon Junco); caniceps (Gray-headed Junco); and insularis (Guadalupe Junco). Furthermore, each group is composed of its former subspecies, if any, whose scientific and vernacular names remain unchanged. For example, the former Junco oreganus mearnsi is now Junco hyemalis mearnsi of the oreganus group, and it retains its long-time vernacular name, Pink-sided Junco. Not all systematists agree with the American Ornithologists' Union's classification, as reported under Systematics (below), but this account follows that classification.

Several sections draw heavily on the authors' studies of the partially migrant Appalachian subspecies J. h. carolinensis; this work has been done in and around Mountain Lake Biological Station (MLBS), Virginia (37°22' N, 80°32' W). Published results will be referred to in the usual way, and unpublished results will be indicated by “MLBS” and/or (in some cases) by the initial(s) of the particular author that was responsible. Statements of age in days are based on MLBS birds that were color-banded as nestlings; statements of age in years rely on those birds that survived into later years plus additional survivors that were banded after nest-leaving but while still in Juvenile plumage. Unbanded yearlings in the second summer of life can be aged by visual inspection (see Measurements, below), and birds banded at that age also supplied some age-related information.

References herein to the “junco” or the “Dark-eyed Junco” apply to the species as a whole and therefore to all its sub-categories. References to a group include all its subspecies; references pertaining to particular subspecies use the appropriate trinomial.

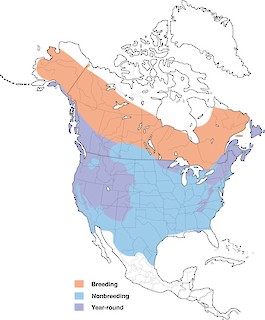

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding