Eurasian Blackbird Turdus merula Scientific name definitions

Text last updated June 20, 2018

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Albanian | Mëllenja |

| Arabic | شحرور |

| Armenian | Սև կեռնեխ |

| Asturian | ñerbatu comñn |

| Azerbaijani | Qara qaratoyuq |

| Basque | Zozo arrunta |

| Bulgarian | Кос |

| Catalan | merla comuna |

| Chinese (SIM) | 欧乌鸫 |

| Croatian | kos |

| Czech | kos černý |

| Danish | Solsort |

| Dutch | Merel |

| English | Eurasian Blackbird |

| English (Australia) | Common Blackbird |

| English (United States) | Eurasian Blackbird |

| Faroese | Kvørkveggja |

| Finnish | mustarastas |

| French | Merle noir |

| French (France) | Merle noir |

| Galician | Merlo común |

| German | Amsel |

| Greek | (Κοινός) Κότσυφας |

| Hebrew | שחרור |

| Hungarian | Fekete rigó |

| Icelandic | Svartþröstur |

| Italian | Merlo |

| Japanese | ニシクロウタドリ |

| Latvian | Melnais strazds |

| Lithuanian | Juodasis strazdas |

| Mongolian | Хар хөөндэй |

| Norwegian | svarttrost |

| Persian | توکای سیاه |

| Polish | kos |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Melro |

| Portuguese (RAA) | Melro |

| Portuguese (RAM) | Melro |

| Romanian | Mierlă |

| Russian | Чёрный дрозд |

| Serbian | Obični kos |

| Slovak | drozd čierny |

| Slovenian | Kos |

| Spanish | Mirlo Común |

| Spanish (Chile) | Mirlo común europeo |

| Spanish (Spain) | Mirlo común |

| Swedish | koltrast |

| Turkish | Karatavuk |

| Ukrainian | Дрізд чорний |

Turdus merula Linnaeus, 1758

Definitions

- TURDUS

- turdus

- merula

- Merula

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

24–27 cm; mainly 85–105 g. Male nominate subspecies is entirely black, with yellow or orange-yellow bill and eyering, blackish legs. Female is dull dark (slightly rufous) brown , paler and vaguely brown-mottled below, with buff-brown submoustachial stripe and throat divided by indistinct malar; bill brownish with some dull yellow basally. Juvenile is dark brown with extensive buff streaking above , double buff-spotted wingbars , buff with extensive dark mottling and streaking below ; first-summer male differs from adult in dusky bill and eyering, browner wings. Subspecies differ mainly in size and in tone of plumage, especially of female: azorensis is smallest, short-winged, female blackish-brown with dark-streaked grayish throat, yellow bill; <em>cabrerae</em> is small, female blackish-brown with limited gray throat, yellow bill; mauritanicus is small, male glossier, female darker with yellow bill; aterrimus is slightly smaller and smaller-billed, male dull black, female paler above and grayer below; <em>syriacus</em> male is more slaty-toned, female grayer; intermedius is large, with largest bill, male sooty black, female blackish-brown.

Systematics History

Editor's Note: This article requires further editing work to merge existing content into the appropriate Subspecies sections. Please bear with us while this update takes place.

Until recently considered conspecific with Chinese Blackbird (Turdus mandarinus) and formerly with Tibetan Blackbird (Turdus maximus) and Indian Blackbird (Turdus simillimus). Proposed subspecies insularum from southern Greek islands (Lesbos, Andros, Ikaria, Samos, Crete, Rhodes) considered indistinguishable from syriacus. Seven subspecies recognized.

Subspecies

Introduced to Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand, subsequently present also on Lord Howe I, Norfolk Is, Macquarie I and Kermadec Is.

Turdus merula merula Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Turdus merula merula Linnaeus, 1758

Definitions

- TURDUS

- turdus

- merula

- Merula

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Turdus merula azorensis Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Turdus merula azorensis Hartert, 1905

Definitions

- TURDUS

- turdus

- merula

- Merula

- azorensis / azorica / azoricus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Turdus merula cabrerae Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Turdus merula cabrerae Hartert, 1901

Definitions

- TURDUS

- turdus

- merula

- Merula

- cabrerae

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Turdus merula mauritanicus Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Turdus merula mauritanicus Hartert, 1902

Definitions

- TURDUS

- turdus

- merula

- Merula

- mauritana / mauritanica / mauritanicum / mauritanicus / mauritanus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Turdus merula aterrimus Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Turdus merula aterrimus (Madarász, 1903)

Definitions

- TURDUS

- turdus

- merula

- Merula

- aterrima / aterrimum / aterrimus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Turdus merula syriacus Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Turdus merula syriacus Hemprich & Ehrenberg, 1833

Definitions

- TURDUS

- turdus

- merula

- Merula

- syriaca / syriacus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Turdus merula intermedius Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Turdus merula intermedius (Richmond, 1896)

Definitions

- TURDUS

- turdus

- merula

- Merula

- intermedea / intermedia / intermedianus / intermedium / intermedius

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

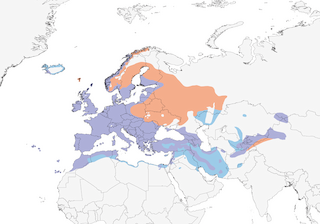

Distribution

Editor's Note: Additional distribution information for this taxon can be found in the 'Subspecies' article above. In the future we will develop a range-wide distribution article.

Habitat

Very broad range, from remote mountainous areas to busy city centres. Main and original habitat relatively open broadleaf, coniferous, mixed and deciduous forests (forest presumed original habitat, although high densities in suburban gardens strongly suggest that species adapted to woodland-edge areas, where greatest abundance of berries and variety of terrestrial foraging micro-habitats exist); also tree plantations, orchards including guava, mango, citrus and olive groves, oases, farmland, gardens and parks, commonly in open grassy areas so long as vegetation cover within short distance. Key requirements in human settlements are well-developed shrubbery (often a function of garden size), open spaces and lower housing densities. Seasonal changes by sedentary populations, e.g. greater use of peripheries of villages (orchards, larger gardens) in autumn and of village centres in winter. Comparison of breeding success in woodland and farmland in Britain suggests that latter slightly suboptimal, with higher proportion of young males, and with smaller eggs laid by females, but overall effects difficult to gauge (distribution in both habitats patchy). In Afghanistan, breeds in river valleys with small trees and bushes, visiting orchards, deciduous forests and thickets in winter. In Morocco, reaches 2300 m, rarely 2700 m, in Oleo-Lentisetum stands, Calenduleta-Junipericum forest and oaks (Quercus); requires areas with more than 300 mm rainfall per year. In Turkey mainly 500–2000 m, locally to sea-level in W.

Movement

Sedentary, partially migratory and fully migratory, depending mainly on latitude. In N Europe , nominate subspecies partly migratory, leaving breeding grounds late Sept, main passage Oct and early Nov (similar dates for birds on same latitudes in Russia), estimated minimum migrant fractions 16% (Denmark), 61% (Norway), 76% (Sweden) and 89% (Finland), with respectively 47%, 75%, 40% and 25% of migrants from these countries moving to Britain and Ireland (others in more S direction to Netherlands, Belgium, NW France); most such migrants female, and probably many young. Those in parts of W & C Europe may be 75% resident, remainder shifting S (some British birds W into Ireland); birds from Germany, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Switzerland and Hungary winter mainly in C & W France, Iberia and N Italy. Russian birds judged to move SW, entering Belarus Aug–Oct, but SE Kazakhstan not vacated until Dec, with concomitant swelling of numbers in Turkey in winter. Subspecies mauritanicus largely resident, but evidence of some S dispersal in winter, and numbers augmented by immigrant nominate subspecies Oct–Apr. Subspecies aterrimus largely sedentary, but some winter in Cyprus and Egypt (latter Oct to mid-Apr), and syriacus also present in Egypt (Mediterranean coast) Nov–Mar. Passage and winter visitor (presumably last two subspecies) mid-Oct to early Apr in Israel, where some movement to lower altitudes by residents in mid-winter. Spring return commences late Feb, with main passage of Scandinavian breeders through W Europe Mar and early Apr, arriving C Sweden late Apr and equivalent latitudes in Russia early May; passage in France appears to show two peaks, one in late Feb and other in mid-Mar, but unclear whether two different breeding populations, two age-classes or different sexes. Vagrants recorded W to Greenland and NE North America, and S to N Indian Subcontinent and Thailand; occasional records in E Saudi Arabia and N Libya involve mostly first-year males, suggesting perhaps pioneering (perhaps enforced) dispersal in late winter.

Diet and Foraging

Invertebrates, mainly earthworms and insects and their larvae , also fruits and seeds and, occasionally, small vertebrates; highly flexible and adaptive, but cannot survive exclusively on fruit for very long. Insect food includes adult and larval beetles (Coleoptera) of at least 13 families, adult and larval lepidopterans of at least ten families, adult and larval flies (Diptera) of at least nine families, bugs (Hemiptera) of at least six families, adult, larval and pupal hymenopterans (including sawflies, ichneumons, ants, bees and wasps), lacewings (Neuroptera) of at least three families, orthopterans (grasshoppers, mole-crickets, bush-crickets), damselflies (Odonata), earwigs (Dermaptera), cockroaches (Blattodea), mayflies (Ephemeroptera) and springtails (Collembola); other animal food includes spiders, harvestmen (Opiliones), woodlice (Isopoda), centipedes (Chilopoda), millipedes (Diplopoda), pseudoscorpions, small molluscs, earthworms, small fish, newts, small frogs, tadpoles, lizards, small snakes and nestling birds. Plant foods mainly fruits and berries but also seeds, key species being strawberry-tree (Arbutus), barberry (Berberis), dogwood (Cornus), hawthorn (Crataegus), strawberry (Fragaria), alder buckthorn (Frangula), ivy (Hedera), juniper (Juniperus), privet (Ligustrum), honeysuckle (Lonicera), apple (Malus), olive (Olea), pistachio (Pistacia), cherries (Prunus), pear (Pyrus), buckthorn (Rhamnus), currant (Ribes), rose (Rosa), bramble (Rubus), elder (Sambucus), brier (Smilax), nightshade (Solanum), rowan (Sorbus), snowberry (Symphoricarpos), yew (Taxus), bilberry (Vaccinium), viburnum (Viburnum), mistletoe (Viscum), vine (Vitis) and maize (Zea). Over year, in Britain, five main food resources: (1) earthworms , consumed throughout but particularly in late summer and autumn; (2) leaf-litter invertebrates, also taken all year; (3) caterpillars and adult insects, mainly late spring and early summer; (4) fruit , Jul–Dec and especially Oct–Nov; and (5) human foodstuffs in various forms. On Heligoland (Germany), spring migrants ate 60% invertebrates (mostly snails and beetles) and 40% man-supplied seeds. In winter, S Spain, food largely vegetable (83% by volume), mainly olives and grapes, with 31% of animal biomass contributed by beetles, but with myriapods dominant in Oct and Dec, and larvae of great importance Jan–Feb. In winter, Italy, vegetable food more frequent (60%) than animal food (40%) and was mainly Pyracantha (38% of total) and Ilex (6%), while animal food was insects (26% of total), worms (6%), millipedes (5%) and spiders (2%); insects composed of beetles (10% of total), bugs (7%), hymenopterans (2%), earwigs (2%), adult and larval lepidopterans (1%), others (4%). At one site in Britain, nestlings provisioned mainly with earthworms and caterpillars, but in another study caterpillars predominated as nestling food in woodland and earthworms in suburban gardens. In Hungary, recorded nestling food earthworms, adult beetles, caterpillars and flies. In orange groves, E Spain, main food of nestlings was earthworms, Helix snails and caterpillars, pupae and imagines of the noctuid moth Peridroma saucia, with secondary prey earwigs, grasshoppers, beetles, bugs, ants, myriapods, spiders and fragments of oranges, and prey types more diverse in Apr than later owing to quantitative changes in prey availability; diet of older nestlings more diverse than that of young or mid-aged ones, owing to decrease in proportion of earthworms and increase in lepidopterans and secondary prey. Forages mainly on ground , by turning leaf litter and uprooting moss with sideways flips of the bill; on grass makes short runs with studied pauses, listening and watching for prey, then stabbing or digging at ground to secure it. Commonly feeds also in trees and bushes.

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Song , by male from elevated perch, a leisurely series of very mellow, slurring whistled phrases (up to 100 phrase types documented in introduced population in Australia), usually ending with short gabbled twitter in which mimicry sometimes present; phrases not repeated (except perhaps early in season); song most complete, rich and complex at dawn, daytime song often less sustained and more distracted; pre-roost song often has curtailed phrases and repetitions, may be given from variety of perches as territory-marking. Female has subsong response during courtship. Subsong of male, fairly common in autumn and winter, a subdued sustained warbling with occasional alarm notes. Calls include high short “sri” for contact in flight and perched, and longer “s’r’r’r’r” in flight; persistent loud nasal “twink twink twink twink…” in aggressive excitement during territorial disputes, pre-roosting behaviour and at presence of cat in breeding territory; low slow clucking “djük”, usually in clusters, in mild alarm, often accelerating into alarm-rattle, a whinny (rising and then falling) in alarm, “djük… djük djük-djükdjük-a-wíítiddli-wíítiddli”; very high, flat, long-drawn, slightly descending “siiiiiiiiii”, frequently repeated in breeding season as warning of aerial predator and when ground predator near nest; slightly lower, softer “suiiiiiiii”, ascending at start and then even-pitched, by territorial male as signal of aggressive readiness; “puk” or “kop” to warn nestlings of ground predator.

Breeding

Mid-Mar to early Sept in Europe, usually from end Apr in both Finland and former Czechoslovakia; Mar–Jun in Canary Is, Mar–Jul in most of N Africa, but Apr–Sept in Tunisia; end Feb to end Jul in Israel; Apr–Jul in Afghanistan; Aug–Feb in Australia (introduced); up to three broods per year. Monogamous pair-bond, but divorce rate in one study 19% between seasons and 5% within season; divorce observed in 32% of 183 cases where birds survived from previous season, and most frequent in low-quality nesting habitat. Solitary, but nests sometimes as close as 10 m where population density very high; territorial. Nest a large cup of dry grass stems and small twigs, packed with mud and lined with fine grass and stems, placed 0·5–15 m off ground in bush or tree or in climbing plant against wall, and frequently in or on wall, outside or inside building; in former Czechoslovakia, 78% of sites in trees and shrubs, 22% in human artefacts, mean height 1·9 m and 94% below 4 m (similar results from Poland); in Tunisian oases nests commonly low in pomegranate (Punica granatum). Eggs 2–6, usually 3–4, pale greenish-blue with pale reddish-brown spots; incubation period 10–19 days, average 13 days; nestling period 13–14 days; post-fledging dependence c. 20 days. Success generally low in urban areas , higher in rural habitats where disturbance levels and numbers of domestic cats lower, but recruitment in urban parks in Spain associated with size of park, shrub cover and height (although human disturbance levels negative); where Common Magpie (Pica pica) densities high, predation can be severe and recruitment depressed below replacement rates; in general, failure rate during incubation significantly greater where corvids more abundant, and in many studies degree of nest concealment correlated with fledging success; of 1428 nests in Britain, one young hatched in 56% and at least one young fledged in 41%; of 6664 eggs laid in 1601 nests in Czechoslovakia, 35·7% lost before fledging; many nests lost to Eurasian Jays (Garrulus glandarius) in Israel and to snakes and children in S Tunisia. Breeds at 1 year; peak reproductive potential in fourth calendar year (clutch size and season length increase with age). Annual adult mortality 44% in Britain, 46% in Belgium (deliberate killing excluded from latter sample), apparent bias in survival towards males (in one study in Britain, male mortality 41%, female 66%), and urban birds (both sexes) suffer lower mortality rates than those in country; annual juvenile mortality in Britain 59% in one study, 58% (analysis 1st Aug to 31st Jul) in another, but in former Czechoslovakia 68%. Causes of mortality of ringed birds in NW Europe are domestic predator 31%, human-related (accidental) 44%, human-related (deliberate) 6%, other 19%.

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). Generally common to abundant. Rather scarce breeder S Tunisia, common in N; abundant in Israel following major expansion of range and numbers since 1940s (attributable in part to development of settlements, gardens and orchards), with total population at least a few hundred thousand pairs (including 1000 pairs in 68 km² of Jerusalem); common in W & S Turkey, sparse and local or absent elsewhere; common in Armenia; sparse in Afghanistan. Total population in Europe in mid-1990s estimated at 37,663,943–54,585,469 pairs, with additional 10,000–100,000 pairs in Russia and 100,000–1,000,000 pairs in Turkey; at that time Spain estimated to hold 2,300,000–5,900,000 pairs, but recently minimum population calculated as 735,232 pairs. By 2000, total European population (including European Russia and Turkey) revised to 40,000,000–82,000,000 pairs and considered generally stable; in 2015, estimated total was given as approximately 55,000,000–87,000,000 pairs. Colonization of European towns began in 1850s; reached Shetland (UK) c. 1880; colonization of Egypt began mid-1970s, and now well established in N; colonization of cities in C Asia also relatively recent. Densities in small urban parks in W Europe are highest recorded, with exceptionally 4 pairs/ha (400 pairs/km²) locally, normally 1·5–2·5 pairs/ha, while in rural areas 0·03–0·1 pair/ha (3–10 pairs/km²) normal. Decline in British population of c. 30% since 1970s, possibly owing to agricultural intensification, as decreases greater on farmland; decline in Netherlands possibly result of lower breeding success. Hunting in Cantabrian Mts, in Spain, may explain relatively low densities there. Hazards for survival in W Palearctic include predators, disturbance, adverse weather conditions, nest collapse and starvation. Australian populations have grown and spread from coast-city introductions between 1850 and 1890 and introduction on Tasmania in early 1900s; populations on Lord Howe I and Norfolk Is (where now very common, first seen c. 1920) came in part from New Zealand , but some may be self-introduced, as may be those on Macquarie I; also well established on some of Kermadec Is.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding