Great Skua Stercorarius skua Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (42)

- Monotypic

Text last updated May 24, 2017

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Arabic | كركر كبير |

| Asturian | Cñgalu grande |

| Azerbaijani | Böyük dənizçi |

| Basque | Marikaka handia |

| Bulgarian | Голям морелетник |

| Catalan | paràsit boreal |

| Croatian | veliki pomornik |

| Czech | chaluha velká |

| Danish | Storkjove |

| Dutch | Grote Jager |

| English | Great Skua |

| English (United States) | Great Skua |

| Faroese | Skúgvur |

| Finnish | isokihu |

| French | Grand Labbe |

| French (France) | Grand Labbe |

| Galician | Palleira grande |

| German | Skua |

| Greek | Αετοληστόγλαρος |

| Hebrew | חמסן גדול |

| Hungarian | Nagy halfarkas |

| Icelandic | Skúmur |

| Italian | Stercorario maggiore |

| Japanese | キタオオトウゾクカモメ |

| Latvian | Lielā klijkaija |

| Lithuanian | Didysis plėšikas |

| Norwegian | storjo |

| Polish | wydrzyk wielki |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | mandrião-grande |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Alcaide |

| Romanian | Lup de mare atlantic |

| Russian | Большой поморник |

| Serbian | Veliki pomornik |

| Slovak | pomorník veľký |

| Slovenian | Velika govnačka |

| Spanish | Págalo Grande |

| Spanish (Argentina) | Escúa Grande |

| Spanish (Spain) | Págalo grande |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Salteador Mayor |

| Swedish | storlabb |

| Turkish | Büyük Korsanmartı |

| Ukrainian | Поморник великий |

Stercorarius skua (Brünnich, 1764)

Definitions

- STERCORARIUS

- stercorarius

- skua

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

53–58 cm; 1100–1700 g; wingspan 132–140 cm. Generally brown plumage but with much white, yellow, ginger and black flecking, individually very variable; birds tend to become paler with age, partly due to retention of back feathers for many years and these fading with wear and exposure, but also due to increased white feathers especially on head . Brown plumage reminiscent of dark juvenile Larus gulls, but distinguished by white wing panels towards bases of primaries; flight much more powerful than that of gulls, with more rapid and stiffer wingbeats; wings shorter and broader than gulls and tail relatively short. Compared to Southern Hemisphere Catharacta has a distinctly dark cap , conspicuous straw yellow hackles, and much rufous streaking, but little contrast between body and wing coloration or tone. Juvenile has much darker and more uniformly coloured plumage, but with general body colour varying from chestnut to brown; white wing flashes, or panels, less evident in juveniles. Timing of moult differs from that of southern Catharacta skuas, which may aid identification. Adult of present species has a prolonged complete post-breeding moult beginning between Aug to early Oct and ending between Jan and mid Mar to Apr. Juvenile has a post-juvenile body moult between Dec and Mar and replace remiges in Mar–Apr and Jun to late Aug (1, 2). In contrast, C. maccormicki is said to have a rapid moult of the remiges (45–60 days compared to 150–180 in C. skua) during the boreal summer, often replacing three or four flight feathers simultaneously (3, 2). However, this distinction has been disputed and recent analyses point to a more complex situation but the two species are separable on primary moult score provided the individuals concerned have been aged accurately (4).

Systematics History

Subspecies

Distribution

Iceland, Faeroes, N Scotland, Jan Mayen, Svalbard, Bear I, Norway and NW Russia (Kola Peninsula, Novaya Zemlya and neighbouring Vaygach I). Winters predominantly off Iberia and NW Africa, south to N Senegal; smaller numbers winter on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. Occasional juveniles move as far S as the Cape Verde Is and Brazil.

Habitat

Marine. Breeds on islands, usually avoiding areas frequented by humans, preferring flat ground with some vegetation cover, but less than 20 cm tall. Often breeds near other seabird colonies, which provide opportunities for kleptoparasitism and scavenging or predation. It largely avoids land during migration and in winter but regularly forages over continental shelf waters a few km offshore. Sizable counts are nonetheless sometimes made from coastal seawatching sites, e.g. Cape Bares, NW Spain and from Portuguese coast (5), particularly when there are onshore winds. Some overland passage does occur, for example across Scotland from the Firth of Forth to Firth of Clyde (6). Winter concentrations are especially associated with areas where it can scavenge from fisheries, e.g. Bay of Biscay, W Mediterranean and off NW Africa. Tends to associate strongly with fishing fleets in winter, where they feed on discards; increased fishery activity off NW Africa appears to have resulted in increased numbers wintering there, off Mauritania (7, 8).

Movement

Migratory, moving S from its breeding areas in Aug–Sept and returning N in Mar–Apr. Different subpopulations tend to winter in different areas. Geolocator studies have found that adults from Scotland wintered off NW Africa and S Europe. Adults from Iceland mostly wintered off Canada, with small numbers visiting NW Africa and Europe. Although adults from Bjørnøya (Norway) migrated to similar areas to birds from Iceland, a slightly greater proportion wintered off Europe, and most used areas further N than birds from Scotland. Although three birds studied over consecutive winters used the same small area in consecutive years, four moved between different areas within one winter (8). Considerable numbers of birds winter in W Mediterranean, entering and leaving via Strait of Gibraltar (5). Some non-breeders remain in Mediterranean and Strait, and in subtropical Atlantic, year-round. The principal E Atlantic winter quarters are off Iberia , from Bay of Biscay and Iberian Atlantic coast and S to coasts of W Africa, as far as Mauritania and N Senegal (8). There are occasional observations and rare ringing recoveries from further S off Africa, from The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau and Ivory Coast (9). In general, adults typically migrate shorter distances, to areas such as Bay of Biscay, and return to the same breeding territory each year (10). Immatures often wander further and have provided ringing recoveries in North and South America (Brazil), West Africa, Greenland and northern Russia (7). Vagrants have occasionally reached Turkey and Black Sea (11, 12).

Diet and Foraging

A highly opportunistic feeder, but also frequently showing individual specializations in diet and feeding, with some colony-specific learning. Birds nesting even within the same colony may show dietary specialization, in particular specializing on fish discards or predation on seabirds (13). In Shetland, feeds chicks mainly on sandeels (Ammodytes) caught by surface-plunging, or on small whiting (Merlangius merlangus), haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus) and pout (Trisopterus esmarkii) discarded from trawlers. Will scavenge on goose-barnacles or dead seabirds , rob Northern Gannets (Morus bassanus) and auks of fish, or kill birds, especially Black-legged Kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla) and Atlantic Puffins (Fratercula arctica). In Iceland and NW Scotland, diet is more varied including some squid and more seabirds. Predation on chicks of Stercorarius parasiticus in Scotland is a factor affecting productivity and nesting locations of the latter (14). Also a serious predator of nesting Leach’s Storm-petrels (Hydrobates leucorhous) on St Kilda, NE Atlantic, capturing large, believed unsustainable, numbers at night both at the petrels’ nesting colonies and offshore (15). Winter diet includes discards and waste from fishing boats, scavenged fish and seabirds, and fish caught or obtained by kleptoparasitism.

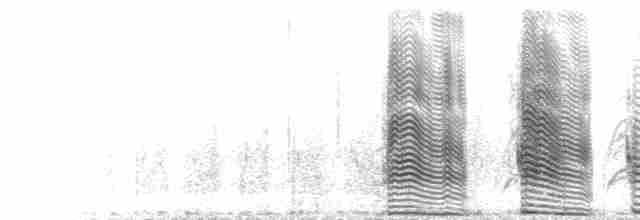

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Mainly vocal on the breeding grounds. Long-call is a series of 5–7 short bleating barks, e.g. “piEh..piEh..piEh..piE..piEh”. Other calls include a low-pitched gull-like “gUk”, a more drawn-out “grAAoo” and a nasal modulated “gyAheheh” when attacking intruders.

Breeding

Starts May. Loosely colonial, highly territorial. Nest scrape usually lined with dead grass. Usually two eggs, but only one laid by some inexperienced birds; incubation 28–32 days; chick has uniformly coloured light pink-grey-brown down; leaves nest 1–2 days after hatching; fledging 40–50 days. Sexual maturity on average at eight years (5–12); adult survival 90% (Shetland).

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). The breeding population, confined to Europe, is estimated at 32,600–34,500 mature individuals. These comprise 9600 pairs in Scotland , mainly in Shetland Is; 5400 pairs in Iceland ; 500 pairs in the Faeroes; 600–1500 pairs on Svalbard ; 115 pairs in Norway; 90–100 pairs in Russia. There were 15 pairs in Ireland in 2012, where first breeding was reported in 2002. Numbers have increased enormously since 1900 when the Scottish and Faeroese populations were close to extinction (see Family Text ). Recent range expansion to Svalbard, Norway, Jan Mayen, Russia and Ireland is continuing, and numbers are likely to increase there. The overall population is now regarded as stable. Recent reductions in sandeel stocks in Shetland have led to declines in breeding success and decreases in numbers at the largest colonies, but increases continue further south in Scotland. However, discards from fisheries provide more than half the summer diet in Shetland, so that changes in fishing practices there and elsewhere could drastically affect numbers (16). Some colonies have been limited in size by human persecution (often illegal). As a top predator, pollutant burdens can be high but there is little evidence of toxic effects. Some birds are drowned in fishing nests or caught on hooks, especially in wintering areas. Harvesting for food has now almost ceased.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding