Gray-headed Albatross Thalassarche chrysostoma Scientific name definitions

- EN Endangered

- Names (31)

- Monotypic

Text last updated March 4, 2017

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Gryskopalbatros |

| Bulgarian | Сивоглав албатрос |

| Catalan | albatros capgrís |

| Czech | albatros šedohlavý |

| Dutch | Grijskopalbatros |

| English | Gray-headed Albatross |

| English (New Zealand) | Grey-headed Mollymawk |

| English (United States) | Gray-headed Albatross |

| French | Albatros à tête grise |

| French (France) | Albatros à tête grise |

| German | Graukopfalbatros |

| Icelandic | Súgtrosi |

| Japanese | ハイガシラアホウドリ |

| Norwegian | gråhodealbatross |

| Polish | albatros szarogłowy |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | albatroz-de-cabeça-cinza |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Albatroz-de-cabeça-cinzenta |

| Russian | Сероголовый альбатрос |

| Serbian | Sivoglavi albatros |

| Slovak | albatros sivohlavý |

| Slovenian | Sivoglavi albatros |

| Spanish | Albatros Cabecigrís |

| Spanish (Argentina) | Albatros Cabeza Gris |

| Spanish (Chile) | Albatros de cabeza gris |

| Spanish (Panama) | Albatros Cabecigrís |

| Spanish (Peru) | Albatros de Cabeza Gris |

| Spanish (Spain) | Albatros cabecigrís |

| Spanish (Uruguay) | Albatros Cabeza Gris |

| Swedish | gråhuvad albatross |

| Turkish | Boz Başlı Albatros |

| Ukrainian | Альбатрос сіроголовий |

Thalassarche chrysostoma (Forster, 1785)

Definitions

- THALASSARCHE

- chrysostoma / chrysostomus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

The Grey-headed Albatross is a member of the “mollymawk” group of southern ocean albatrosses. Containing five species, the mollymawks are distinctive as a group with dark wings and back, white underparts, and rump, but separable from each other by distinctive combinations of plumage (especially of the head) and bill color. The adult Grey-headed Albatross is identified by the combination of a gray head and an orange-tipped black bill, with yellow along the ridge of the mandible and maxilla. If seen well, the adult is distinctive, but due to its delayed maturation, juvenile and sub-adult plumages are less distinctive and birds in these plumages may be confused with other mollymawks. The Gray-headed Albatross breeds on widely scattered islands in the southern oceans. It breeds in South America on the Diego Ramirez Islands, off Tierra del Fuego, but also occurs as a nonbreeder in cold pelagic waters off both coasts.

Field Identification

70–85 cm (1); male 3096–4345 g, female 2840–4175 g (2); wingspan 180–220 cm. Clearly hooded, but only indistinctly capped . Adult has grey hood , darkest next to eye as in other mollymawks but often less contrastingly browed, conspicuous and clear-cut white crescent framing lower and rear half of eye , forehead and forecrown diffusely paler, but no capped pattern, often fading whiter on throat and foreneck, and neck can be paler grey as well, with dark brownish-grey mantle; back, scapulars and especially upperwing blackish brown , outer primaries with white shafts; tail grey; underwing white with broader blackish margins than most mollymawks , broadest on basal third of leading edge; breast and rest of underparts white; iris dark brown to blackish; bill black with rich yellow on upper and lower ridges, orange-red on maxilla, yellow on mandible does not reach tip and forms narrow yellow basal line with thin black line at very base; gape rich yellow ; legs pale pinkish and pale bluish grey. Sexes similar, but female averages smaller in most measurements (2). Bill colours form unique pattern, but see T. chlororhynchos and T. bulleri; from former by strongly capped appearance, and from both by broader blackish leading edge to underwing; T. melanophris has similar underwing pattern, but bill colour and paler head/neck prevent confusion; underwing has less black at ‘wrist’ and ‘elbow’ than Phoebastria immutabilis. Juvenile has blackish bill and dark underwing, brownish-grey hood usually darker but less even on face, pale crescent framing rear of eye usually inconspicuous, and may have whitish areas on crown and face; separation from juvenile T. melanophris can be tricky, but present species usually has greyer head and darker bill base (2).

Systematics History

Subspecies

Hybridization

Hybrid Records and Media Contributed to eBird

-

Gray-headed x Black-browed Albatross (hybrid) Thalassarche chrysostoma x melanophris

Distribution

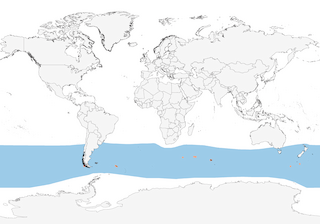

Circumpolar in Southern Ocean, breeding from Cape Horn E to Campbell I.

Habitat

Marine and pelagic , rarely approaching land except at colonies; favours much colder surface waters than most other albatross species. Breeds on remote oceanic islands occupying steep slopes or cliffs, generally with tussock grass .

Movement

Disperses widely over Southern Ocean, mostly between 65° S and 35° S, reaching 15° S in zone of Humboldt Current. During non-breeding season South Georgia birds have been recorded making one or more global circumnavigations, the fastest in just 46 days, whereas all New Zealand-banded birds have been recovered W of New Zealand in Australian zone. Tracked birds from South Georgia spent during the non-breeding period a large proportion of time in the SW Atlantic, N of the colony between the Polar Front and the Subtropical Front, E of the Falkland Islands, and around the South Sandwich Fracture Zone, and they also foraged around the Subtropical Front in the SW Indian Ocean and NE of the Kerguelen Plateau towards the Southeast Indian Ridge; in contrast, similarly tracked birds from the Prince Edward Islands spent a large proportion of time in the Indian Ocean, around the colony towards the Southwest Indian Ridge, and in the SE Indian Ocean between the Kerguelen Plateau and Southeast Indian Ridge, but they also foraged towards the Humboldt Upwelling, SE Pacific Ocean (3). Among the birds form South Georgia, previously failed birds segregated spatially from successful birds during summer, when they used less productive waters, suggesting a link between breeding outcome and subsequent habitat selection (3). One individual has been recorded traveling, during a regular foraging trip, at minimum average ground speed of >110 km/h for c. 9 hours (4). No reliable records from N Hemisphere; in S African region very rare even as far N as Namibia (5) and just one record in tropical Pacific, from Tahiti, French Polynesia (17º S) (6).

Diet and Foraging

Mainly cephalopods (Todarodes, Kondakovia longimana, Histioteuthis eltaninae) and fish (Myctophidae, Channichthys rhinoceratus, Dysalotus alcockii); also crustaceans (Euphausia superba) and carrion; lampreys (Geotria australis) locally important. High proportion of squid in diet at South Georgia may account for longer nesting period than T. melanophris, which takes mostly krill; five cephalopod species belonging to five families (Gonatidae, Onychoteuthidae, Psychroteuthidae, Ommastrephidae and Cranchiidae) contributed 98% by number and 97% of biomass fed to chicks at South Georgia, where the most important species was the ommastrephid Martialia hyadesi, contributing 68·9–77·4% by number and 72·5–79·3% of total biomass (7). However, inter-annual variation in diet well-documented (8), thus at same site, during unusually warm weather in Mar/Apr 2000, fed mainly on krill (Euphausia superba; 77% by mass) (9). Most food taken by surface-seizing, but also uses surface-diving and shallow-plunging to access some items (1), sometimes reaching up to 6 m (usually less than 1 m) (2). Diving mostly occurs during daylight and this technique can yield up to 30–45% of daily food requirements (2). Does not usually follow ships (except around Falkland Is) (1) and attends fishing boats less regularly than other species; regularly associates with other tubenoses (10, 11) and cetaceans (e.g. killer whales Orcinus orca) (12), except around New Zealand (1). Will congregate in larger groups at plentiful food source, but usually observed alone or in small groups (1).

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Wailing and croaking calls like those of most other mollymawks, especially T. melanophris (1).

Breeding

Biennial, when successful; starts early Sept–Oct with return to colony, thereafter pre-laying exodus (by females) lasts on average c. 16 days, egg-laying occupies c. 20 days at most colonies (mean date usually 20 Oct), hatching mostly early Dec and colony deserted by May (late Apr on Macquarie I) (13), thus overall attendance at colony is c. 239 days (2). Monogamous and pair-bonds probably life-long (1). Colonial, forming colonies of 15–10,000 pairs; large nest of mud and grass, with central depression. Single whitish egg, marked with fine red spots at large end (1), mean size 106 mm × 68 mm, mass 276 g (2); incubation c. 69–78 days (1) with stints of 5–15 days (first shifts long, later ones shorter) (2); chicks have white or pale grey down, whitest on face, being fed every 1·26 days with mean meal size of 616 g (14); fledging mean c. 141 days when 3500–4000 g, but reaches peak mass of 3500–4900 g when c. 90 days old (2). At Diego Ramírez Is (off Cape Horn), breeding adults undertake foraging trips of between 2500 km and 12,000 km (15), while on Marion I, during incubation, birds make long foraging trips, mostly towards subtropical convergence and subantarctic zones, whereas during early chick-rearing stage, foraging trips are shorter and to polar frontal and Antarctic zones, with males making higher proportion of short trips (16). At South Georgia foraging trips can occupy up to 28 days (9, 17). Overall breeding success estimated at 58% on Macquarie I (18) and 39% at South Georgia (just 28% in 1984) (19), where 60% of eggs hatch and 65% of chicks fledge (20); < 1% of successful birds breed the next year (versus 5% on Marion I) (21), 68% return to breed two years later, 11% the next and 5% not until the fourth year, in contrast > 50% of birds that fail to rear a chick breed the next year, but 23% delay another year, and birds that fail later than March do not return next year, whereas 80% that fail during incubation do breed the following year (20). Sexual maturity at 8–14 years, although birds may first return to colonies at 3–5 years (more usually 6–7) (2). Senescence appears to set in after age 28 years (17). Adult mortality of c. 5–7% per year and at least some birds have been recorded living up to 44 years (17), while survival of fledglings to breeding age at South Georgia was estimated at 35–36% (1959–1964 cohorts), although this subsequently crashed to just 7–8% (1976–1981) and probably reached below 5% (1982–1986) (2). At Macquarie, juvenile survival was estimated at 33·6% between 1975 and 2000 (22).

Conservation Status

ENDANGERED. World population estimated at c. 500,000–600,000 birds in late 1990s, with c. 80,000–95,000 pairs breeding in any one year; 17,000 pairs on Diego Ramírez Is (2002, where numbers apparently increasing) (23), formerly 61,500 pairs at South Georgia including Bird I and Willis Is (2) (but population estimated to have declined by 25% since 1977, leading to revised estimate of 47,700 pairs in 2004) (24), 6400 pairs (2) at Campbell I (formerly 11,530 pairs, major decline between 1940s and 1997 but numbers have apparently stabilized since) (25); c. 20,000 pairs in S Indian Ocean at Kerguelen (7900 pairs), Crozet (5940 pairs) and Prince Edward Is (7700 pairs, where increasing on Marion I) (26, 27, 28); only very small numbers on Macquarie I (78 pairs in 1998/99 and population apparently stable since mid 1970s) (29, 22). In early 20th century egg collecting produced significant decline, but nowadays only occurs very rarely. Numbers apparently fairly stable at most breeding stations but significant recent decline at South Georgia (20); slight local decreases especially connected with habitat destruction and predation by alien mammals, e.g. cats, rats, but also due to launch of squid fishery and longline fishing for Patagonian toothfish (Dissotichus), although only comparatively small numbers were taken off SW Argentina in 1999–2001 (30). Mortality (especially of immatures) has increased at commercial fishing grounds, especially off South Africa (31), Australia (32) and in S Indian Ocean (33, 34, 35), where most die incidentally, although mitigation factors have now been developed (36, 37); at South Georgia, less affected by competition with fisheries than is T. melanophris.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding