Osprey Pandion haliaetus Scientific name definitions

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Visvalk |

| Albanian | Shqiponja peshkngrënëse |

| Arabic | عقاب نساري |

| Armenian | Ջրարծիվ |

| Asturian | ñguila pescadora |

| Azerbaijani | Çay qaraquşu |

| Basque | Arrano arrantzalea |

| Bulgarian | Орел рибар |

| Catalan | àguila pescadora |

| Chinese | 魚鷹 |

| Chinese (Hong Kong SAR China) | 鶚 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 鹗 |

| Croatian | bukoč |

| Czech | orlovec říční |

| Danish | Fiskeørn |

| Dutch | Visarend |

| English | Osprey |

| English (United States) | Osprey |

| Faroese | Fiskiørn |

| Finnish | sääksi |

| French | Balbuzard pêcheur |

| French (France) | Balbuzard pêcheur |

| Galician | Aguia pescadora |

| German | Fischadler |

| Greek | Ψαραετός |

| Haitian Creole (Haiti) | Malfini lanmè |

| Hebrew | שלך |

| Hungarian | Halászsas |

| Icelandic | Gjóður |

| Indonesian | Elang tiram |

| Italian | Falco pescatore |

| Japanese | ミサゴ |

| Korean | 물수리 |

| Latvian | Zivju ērglis |

| Lithuanian | Žuvininkas |

| Malayalam | താലിപ്പരുന്ത് |

| Marathi | कैकर |

| Mongolian | Загасч явлаг |

| Norwegian | fiskeørn |

| Persian | عقاب ماهیگیر |

| Polish | rybołów |

| Portuguese (Angola) | Águia-pesqueira |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | águia-pescadora |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Águia-pesqueira |

| Romanian | Uligan pescar |

| Russian | Скопа |

| Serbian | Ribar |

| Slovak | kršiak rybár |

| Slovenian | Ribji orel |

| Spanish | Águila Pescadora |

| Spanish (Argentina) | Aguila Pescadora |

| Spanish (Chile) | Águila pescadora |

| Spanish (Costa Rica) | Águila Pescadora |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Guincho |

| Spanish (Dominican Republic) | Guincho |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Águila Pescadora |

| Spanish (Honduras) | Águila Pescadora |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Águila Pescadora |

| Spanish (Panama) | Águila Pescadora |

| Spanish (Paraguay) | Águila pescadora |

| Spanish (Peru) | Aguila Pescadora |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Águila Pescadora |

| Spanish (Spain) | Águila pescadora |

| Spanish (Uruguay) | Águila Pescadora |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Águila Pescadora |

| Swedish | fiskgjuse/australisk fiskgjuse |

| Thai | เหยี่ยวออสเปร |

| Turkish | Balık Kartalı |

| Ukrainian | Скопа західна |

Pandion haliaetus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- PANDION

- pandion

- haliaetus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

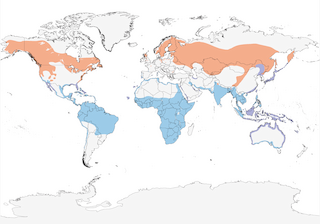

Among the World's best-studied birds of prey, the widely admired Osprey is the only raptor that plunge-dives to catch live fish as its main prey source. Despite its reliance on fish, the Osprey occupies a broad array of habitats, ranging from mangrove islets to boreal forest lakes, and from salt marshes to saline lagoons. Northern populations migrate south to overwinter primarily on fish-rich rivers, lakes, and coastal areas in subtropical and tropical regions, returning north each spring as waters warm and fish become accessible. An Osprey nesting in a northern region and overwintering south of the equator might fly more than 200,000 kilometers during its 15 to 20-year lifetime.

The Osprey dives feet first to capture prey, accessing only about the top meter of water, so it is restricted to foraging for surface-schooling fish and to those in shallow water—the latter generally are most abundant and available. As a result, in many areas it tends to breed most densely where shallow waters abound. In many of these places, artificial nest sites, or nest platforms, have helped breeders enormously in recent decades. Historically, the Osprey built its bulky stick nest atop trees, rocky cliffs, promontories, and even on the ground on a few islands that lack mammalian predators. While some continue to use natural sites, many have shifted to nesting on artificial structures. The species now uses an astonishing array of artificial sites: channel markers in harbors and busy waterways; towers for radio, cell phone, and utility lines; and platforms erected exclusively for the species. This shift has been dramatic in many regions, with 90–95% of pairs choosing to nest at artificial sites; predation, loss of trees, and development of shorelines have been driving forces behind the change.

In North America, the Osprey gained increased recognition from the 1950s to 1970s because populations crashed in several key regions. About 90% of the pairs nesting along the Atlantic coast between New York City and Boston, for example, disappeared during this period; Chesapeake Bay lost more than half of its breeding pairs, and Great Lakes populations also suffered major declines. Studies showed that high levels of contaminants (especially DDT and its derivatives) in eggs, severe eggshell thinning, and poor hatching success were responsible. Mortality of adults may have contributed to the decline. Osprey studies provided key evidence in court to block continued use of persistent pesticides, and Osprey populations recovered rapidly thereafter. Although small pockets of contamination remain, the historic range has greatly expanded and many populations in Canada and the United States now exceed historical numbers, owing to a cleaner environment, increasingly available artificial nest sites, and this bird’s ability to tolerate human activity near its nests. Phoenix-like, the Osprey has arisen from the ashes of its own demise, a survivor, even a backyard bird in some areas today. Indeed, there is little wonder the species has become such a powerful totem for conservation.

Concern for populations impacted by pesticides spawned a multitude of studies on Osprey life history during the 1970s and 1980s, and these have continued almost undiminished since then—the product of Osprey allure, broad distribution, and ease of study (highly visible nesting and hunting, and accessible nests). The life history of the Osprey in North America was summarized by Bent (Bent 1937b), Palmer (Palmer 1988e), and Poole (Poole 1989a), whereas Cramp and Simmons (Cramp and Simmons 1980b) and Dennis (Dennis 2008) did the same for Osprey breeding in the Palearctic. Although this account, by necessity, leans on these earlier works, we have emphasized more recent studies. Areas of important new research include: analyses of migratory movements based on satellite tracking (Martell et al. 2001a, Martell et al. 2014, Washburn et al. 2014); navigational abilities (Horton et al. 2014); behavior at the nest (Birkhead and Lessels 1988, Bretagnolle and Thibault 1993); molecular genetic studies to determine Osprey systematics (Seibold and Helbig 1995b) and phylogeography (Monti et al. 2015); foraging and development of dietary preferences in the postfledging period (Edwards and Collopy 1988, Edwards 1989b); assessment of contaminants in western populations (Henny et al. 1991b, Elliott et al. 1994, Elliott et al. 2000, Elliott et al. 2001b); status of North American populations in the Great Lakes (Ewins 1995, Ewins 1996, Ewins 1997, Ewins et al. 1995a, Ewins et al. 1999); sibling aggression among nestlings (Forbes 1991); colonial nesting (Hagan and Walters 1990); lifetime reproduction (Postupalsky 1989b); and growth of nestlings (Steidl and Griffin 1991, Schaadt and Bird 1993).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding