Red Junglefowl Gallus gallus Scientific name definitions

Text last updated November 7, 2015

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Rooiboshoender |

| Assamese | বন কুকুৰা |

| Bulgarian | Банкивска кокошка |

| Catalan | gall bankiva |

| Chinese (SIM) | 红原鸡 |

| Croatian | divlja kokoš |

| Czech | kur bankivský |

| Dutch | Bankivahoen |

| English | Red Junglefowl |

| English (United States) | Red Junglefowl |

| French | Coq bankiva |

| French (France) | Coq bankiva |

| German | Bankivahuhn |

| Greek | Κότα |

| Haitian Creole (Haiti) | Poul |

| Hebrew | תרנגול בר |

| Icelandic | Bankívahænsn |

| Indonesian | Ayam-hutan merah |

| Italian | Gallo bankiva |

| Japanese | セキショクヤケイ |

| Norwegian | bankivahane |

| Polish | kur bankiwa |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Galo-bravo-vermelho |

| Russian | Банкивский петух |

| Serbian | Indijska divlja kokoš |

| Slovak | kura divá |

| Slovenian | Bankivska kokoš |

| Spanish | Gallo Bankiva |

| Spanish (Dominican Republic) | "Gallina, Gallo" |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Gallo Doméstico |

| Spanish (Panama) | Gallo Salvaje Rojo |

| Spanish (Peru) | Gallo |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Gallo Silvestre |

| Spanish (Spain) | Gallo bankiva |

| Swedish | röd djungelhöna |

| Thai | ไก่ป่า |

| Turkish | Yaban Tavuğu |

| Ukrainian | Курка банківська |

Gallus gallus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- GALLUS

- gallus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

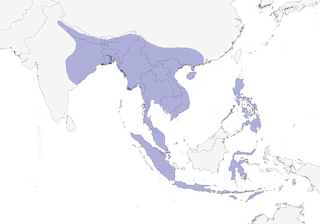

The Red Junglefowl is a name used for both the ancestral stock of the domestic chicken and for feral populations derived from introduced domestic chickens. Smaller in size and slimmer than most chicken breeds, the Red Junglefowl has buffy or bronze neck feathers extending down over the back and a metallic blue to green arching tail. Native of southeast Asia from India through southern China and down to Indonesia, it has become feral in several regions around the world including Hawaii and the Caribbean. Feral birds are often very difficult to distinguish from free-ranging domestics and frequently both inhabit the same island, though feral birds are often secretive and difficult to see. In the Caribbean there are feral populations in Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Guadeloupe, and the Grenadines.

Field Identification

Male 65–78 cm (1), 672–1450 g; female 41–46 cm (1), 485–1050 g. Male differs from that of G. lafayettii in form of comb and by absence of heavy streaking. In non-breeding plumage (Jun–Sept), which was apparently unknown in extreme E populations (2), male sheds golden hackles (thus feathers of head and neck are dull black, short and blunt) and elongated tail feathers, has reduced and paler comb, but retains rufous in wings (1); however, such eclipse plumages have been gradually lost among wild populations, apparently due to genetic introgression with domesticated birds (2). Female differs from those of G. sonneratii and G. lafayettii by absence of bold pattern on underparts; and from those of G. lafayettii and G. varius by lack of bold pattern on flight feathers. Bare parts: bill horn (almost pale pinkish when breeding), irides pale orange to reddish brown (male) or brown (female) and legs grey or brownish grey; male has single, long spur, female none or only a very short spur (1). Recent studies of free-living captive birds have found that some male characters, e.g. the spur and or head adornments (comb etc.) may develop asymmetically, but significance of this yet to be fully understood (3). First-year male similar to adult male, but is overall duller with shorter hackles (1). Juvenile is much like adult female , but has darker underparts; young male soon develops reddish-yellow hackles and some red on back, and has blacker tail than female (1). Variation between races is most noticeable in colour, length and shape of male’s hackles during breeding season: redder, shorter and rounded in bankiva, which race is most like spadiceus (1); pointed and with dark shaft-streaks in <em>murghi</em> , which has paler orange hackles on rump, smaller and white ear-lappets , and female is paler than in other races (1); race <em>jabouillei</em> is somewhat intermediate, with smaller all-red lappets (1) and comb and (golden-yellow) (1) hackles, and female <em>jabouillei</em> is generally rather darker than nominate female; while race <em>spadiceus</em> has neck-hackles shorter and more golden-yellow than in nominate (in which they are golden-orange to bright red), while the ear-lappets are small and all red (large and white in nominate gallus) (1). Identifying wild versus domesticated (yet feral) populations can be very difficult in some regions, but body feathers (in genetically pure birds, all black in males, mottled brown in females), tail size (relatively short, not exceptionally elongated) and colour (all black in males, brown in females), legs (slender and dark, not thick and yellow), wing colour (all black in males or brown in females), comb (small and simple, not large and elaborate), hackle colour (bright orange), spurs (relatively small and short), and collar colour (black in males or brown in females) provide some level of reliability, especially in combination (4).

Systematics History

Editor's Note: This article requires further editing work to merge existing content into the appropriate Subspecies sections. Please bear with us while this update takes place.

Closely related to G. sonneratii and G. lafayettii; hybridizes locally with G. sonneratii in areas of contact. An attempt to re-create the phylogeographical history of both wild and captive populations of this species identified nine highly divergent mtDNA clades (seven common to both populations), with three clades widely distributed in Eurasia, but the others restricted to S & SE Asia—one in Japan and SE China, two exclusive to Yunnan (S China), and another closely related to distribution of cock fighting; patterns suggest that different clades arose in different regions, e.g. Yunnan, S & SW China and/or surrounding areas, and Indian Subcontinent, respectively, thus supporting theory of multiple origins in S & SE Asia (5). Geographical variation clearly clinal; intergradation occurs between at least three (probably four) of the accepted races. Proposed race gallina (from Himachal Pradesh, in N India) treated as a synonym of murghi; some introduced populations have been described as races, e.g. in Philippines (philippensis) and Micronesia (micronesiae), but none considered valid. Five subspecies usually recognized.Subspecies

Occurs also in Philippines, Sulawesi and parts of Lesser Sundas, where probably introduced. Introduced or feral in many areas, including throughout Micronesia, Melanesia and Polynesia; Reunion and the Grenadines; probably also New Zealand and South Africa.

Gallus gallus murghi Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Gallus gallus murghi Robinson & Kloss, 1920

Definitions

- GALLUS

- gallus

- murghi

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Gallus gallus spadiceus Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Gallus gallus spadiceus (Bonnaterre, 1792)

Definitions

- GALLUS

- gallus

- spadicea / spadiceus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Gallus gallus jabouillei Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Gallus gallus jabouillei Delacour & Kinnear, 1928

Definitions

- GALLUS

- gallus

- jabouillei

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Gallus gallus gallus Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Gallus gallus gallus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- GALLUS

- gallus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Gallus gallus bankiva Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Gallus gallus bankiva Temminck, 1813

Definitions

- GALLUS

- gallus

- bankiva

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Distribution

Editor's Note: Additional distribution information for this taxon can be found in the 'Subspecies' article above. In the future we will develop a range-wide distribution article.

Habitat

Throughout extensive range, occupies most tropical and subtropical habitats, including mangroves, from sea-level up to c. 2000 m (in Bhutan (6), Malaysia and SW China) (1) and even 2400 m in NE India (7). Even within introduced range, e.g. on Samoa, ranges to at least 1200 m (8). Appears to prefer flat or gently sloping terrain, and edge or secondary habitats over forest, although in Arunachal Pradesh densities are clearly greater in unlogged forest (9) and on Palawan denstities were at least twice as high in old-growth forest versus cultivation and early and advanced second-growth habitats (10). Nevertheless, in some areas, e.g. Bhutan, it regularly enters scrub near villages and even fields, to feed (6). Clear habitat segregation in areas of overlap with G. varius, with latter favouring more open areas, while in India, where sympatric with G. sonneratii, the present species is closely associated with moister sal (Shorea robusta) forest, whereas sonneratii prefers drier teak (Tectona grandis) forest (1).

Movement

None described and presumably none undertaken, as extremes of climate are limited in most of range; nevertheless, in N Thailand, birds apparently descend to lower altitudes in winter.

Diet and Foraging

Opportunistic and omnivorous; probably shows seasonal preferences, depending upon availability. Gut contents of 37 birds in India contained seeds of 30 species and many invertebrate taxa; plant genera taken include Trichosanthes (Cucurbitaceae), Rubus (Rosaceae), Carissa (Apocynaceae), Zizyphus (Rhamnaceae) and Shorea (Dipterocarpaceae); only cultivated plant species was rice (Oryza, Poaceae). Similarly wide range of food items found in 23 crops from Thailand, including Euphorbiaceae fruits, bamboo seeds and Zizyphus fruits. Insects recorded include ants, beetles and termites (nearly 1000 Macrotermes carbonarius in one crop) (11) and their eggs. Food procured by scratching ground and picking at items (1). Visits more open areas in early morning and evening to feed, and waterholes on daily basis during dry periods (1). Usually seen in small groups , especially in winter, often comprising a male with several females (1), and is sometimes observed joining groups of Lophura diardi in C Thailand (12). Groups said to congregate at seeding bamboo in some areas. May also associate with mammals, wild and domestic, taking insects flushed by them or attracted to their dung, once even observed taking maggots in a head-wound to an animal (11).

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Male advertising call , mainly given at dusk or dawn close to roost, is similar to but shriller then well-known “cock-a-doodle-do” of village chicken, as well as having a more strangulated finale; in Bhutan, mostly heard mid Feb to mid May (6). Large number of different calls (c. 30) including many clucks (“bok-bok-bok...bok-ber...”) (13) and cackling sounds in alarm (an explosive “KERCH!-ERCH!-ERCH!-ERCH!” that falls away) (13) and when feeding (1).

Breeding

Mar–May, during dry season, in India, although eggs found Jan–Oct in different parts of country; Mar–Jun in Bangladesh; Dec–Jun and Aug in Thai-Malay Peninsula (11); and Feb–May in China, where earliest records are from S Yunnan. Polygamous, with the number of females associated with a given male appearing to increase as breeding season advances, but monogamy also reported and may be reasonably frequent in some areas (1). Nest-sites varied, but typically a shallow scrape in dense secondary growth or bamboo forest, lined with dry grass, palm fronds and bamboo leaves (1), and sited under bushes or in clumps of bamboo, but sometimes in tree fork (13). Usually 5–6 white, or pale buff to pale reddish-brown (1) eggs (range 4–12) (1), size 45–49 mm × 36 mm (Malaysia) (11), incubated 18–21 days (1), by female alone, for which visual clues are extremely important in determining incubation behaviour and thus clutch size (14) (experiments in captivity suggest that incubation becomes continuous only with final egg (14) and that females that are heavier produce larger eggs, more male offspring and lay earlier, but do not produce larger clutches) (15); chicks (able to fly at c. 1 week) (1) have maroon-brown down above, whitish buff below , browner on breast; tended by female alone (11). In captivity, a dominant male is able to copulate with more females than subordinate individuals (16) while breeding success is positively correlated with a female’s dominance within the flock, lifespan and year of hatching (17). Females prefer males with longer and redder combs, but apparently pay little heed to other plumage characters in their mate choice (18), and in captivity produce more eggs in response to being paired with preferred mates (19). It also appears from experiments conducted in captivity that laying behaviour (egg output) may differ between females in potentially monogamous pairings and those that frequent harems (14). At least in captivity, males become sexually mature when 5–8 months old; infection prior to this age with the intestinal parasite Ascaridia galli (which affects both domestic chickens and wild birds) can lead to males having smaller combs, and at some ages, lower body mass and shorter tarsi (16).

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). Mace Lande: safe. Distributed over large range (c. 5,100,000 km²) and occurs in varied habitats, including secondary vegetation and anthropogenic sites, such as rubber and oil-palm plantations. In Thailand, considered widespread and common, with estimated population in hundreds of thousands, despite relentless persecution; still more or less common in Peninsular Malaysia (11). Last remaining habitat in Singapore under severe threat (20). In Indonesia, still widespread but declining due to habitat loss and degradation, as well as hunting; not particularly common on Java, Sulawesi (where heavily hunted and declines > 50% have been reported even inside reserves) (21) or Lesser Sundas, but rather common on Sumatra. Not protected by Indonesian law. In India, numbers considered stable in protected areas, but declining elsewhere due to habitat degradation and overhunting for food, e.g. in Nagaland (22), and overall the species is known from fewer localities than it was historically, although there is no evidence for a contraction in range (23). Locally common in Nepal, where known from several localities, e.g. Sukla Phanta, Bardia, Chitwan and Kosi Tappu, but few records elsewhere, and is believed to have declined recently, being apparently been shot out in some areas. Known from at least 190 protected areas across India alone (23) and at least 100 elsewhere throughout range (1). Widely introduced in domesticated form—the species was already domesticated in Indus Valley by c. 2500 BC and had been introduced to C & NW Europe by 1500 BC (24). Elsewhere feral populations occur or have occurred as follows: Cocos (Keeling) and Christmas Is, Borneo, the Lesser Sundas (including Lombok, Roti (25), Timor, Lembata (26) and Wetar ), various of the Philippines , including Palawan (from c. 1521), Mindoro (27), Negros (28), Siquijor (where apparently extinct) (29), Bohol (30) and Cebu (where once thought extinct) (31), Balabac, Sulawesi, the Togian (32) and Banggai Is (33), Papua New Guinea (e.g., introduced in Bismarck archipelago at least c. 2700 years ago) (34), Easter I (prior to 1770) (35), Latin America (from Mexico to Chile and the Galápagos Is; perhaps brought to mainland South America from China in 15th century), the West Indies (Little San Salvador I, Dominican Republic, Mona and possibly Culebra, and the Grenadines), Hawaii (suspected to have been brought from E Asia, by 500 AD, but also imported from the mainland USA in 1963) and very widely in Polynesia (introduced from E Asia c. 3000 years (24), although Caroline Is population shows no phenotypic evidence of being domesticated) (4). Speculated that G. gallus could have introduced exotic diseases that caused decline of some endemic bird species in Polynesia (8). Because of the widespread prevalance of domestic stock, including throughout much of the species’ native range, concerns have been raised that extensive hybridization with domestic or feral chicken populations is swamping ‘wild type’ genomes, leading to loss of original genotypes (4) (e.g., in Peninsular Malaysia) (1). One signal of this collapse in genetic integrity has been the loss of eclipse (non-breeding) male plumage; this indicator of the pure wild genotype certainly originally occurred in populations in western and central portions of the species’ range, but probably disappeared from extreme SE Asia and the Philippines prior to the 1860s and has not been observed in Malaysia and neighbouring countries since the 1920s, but did persist in NE India until as late as the 1960s (2).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding