Silver Gull Chroicocephalus novaehollandiae Scientific name definitions

Text last updated September 7, 2015

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Bulgarian | Австралийска чайка |

| Catalan | gavina australiana |

| Chinese | 紐澳紅嘴鷗 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 澳洲红嘴鸥 |

| Czech | racek australský |

| Danish | Perlegrå Måge |

| English | Silver Gull |

| English (United States) | Silver Gull |

| Finnish | hopealokki |

| French | Mouette argentée |

| French (France) | Mouette argentée |

| German | Silberkopfmöwe |

| Icelandic | Skerjamáfur |

| Indonesian | Camar perak |

| Japanese | ギンカモメ |

| Norwegian | australmåke |

| Polish | mewa czerwonodzioba |

| Russian | Австралийская чайка |

| Serbian | Crvenokljuni galeb |

| Slovak | čajka striebrohlavá |

| Slovenian | Avstralski galeb |

| Spanish | Gaviota Plateada |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Silver Gull |

| Spanish (Spain) | Gaviota plateada |

| Swedish | silvermås |

| Turkish | Avustralya Martısı |

| Ukrainian | Мартин австралійський |

Chroicocephalus novaehollandiae (Stephens, 1826)

Definitions

- CHROICOCEPHALUS

- novaehollandae / novaehollandia / novaehollandiae

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

38–43 cm; 195–430 g (nominate) or 150–366 g (scopulinus); wingspan 91–96 cm. White head, body and tail, blending into grey mantle, back and wings; outer primaries mostly black, with white subterminal spots on outermost three, inners white at bases; bill entirely bright red; legs dull red; iris whitish, with narrow fleshy red orbital ring. Bare-part colours duller in W than in E. Sexes differ in bill depth, male > 11 mm and female < 11 mm. Juvenile has brown markings on head, brown-mottled mantle , scapulars and upperwing-coverts, and a dark brown subterminal band on the tail; bill, iris and orbital ring dark; legs vary from flesh to blackish. Moults into adult plumage at c. 12 months. Race forsteri differs in being slightly larger, while smaller <em>scopulinus</em> also differs from nominate only in bill shape , sometimes has greyish wash to nape, rarely has white mirror on p8 and mirrors on pp9–10 are shorter than wider than on same feathers in nominate.

Systematics History

Editor's Note: This article requires further editing work to merge existing content into the appropriate Subspecies sections. Please bear with us while this update takes place.

Some recent authors place this species and other “masked gulls” in genus Chroicocephalus (see L. philadelphia). A recent molecular study indicated that this species was sister to L. bulleri (1). May be closely related to, and is sometimes considered conspecific with, L. hartlaubii. Morphometric analysis of skeletal characters links present species with L. serranus, L. maculipennis and L. cirrocephalus. Race scopulinus sometimes treated as a separate species (e.g. in HBW), but distinguishing characters few and minor; scopulinus hybridizes with L. bulleri rarely, even where breeding alongside (L Rotorua). Tasmanian birds sometimes separated as race gunni, but variation only clinal. Three subspecies recognized.Subspecies

Silver Gull (Silver) Chroicocephalus novaehollandiae novaehollandiae/forsteri

Distribution

Chroicocephalus novaehollandiae forsteri (Mathews, 1912)

Definitions

- CHROICOCEPHALUS

- novaehollandae / novaehollandia / novaehollandiae

- forsteri / forsterii / forsterorum

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Distribution

Chroicocephalus novaehollandiae novaehollandiae (Stephens, 1826)

Definitions

- CHROICOCEPHALUS

- novaehollandae / novaehollandia / novaehollandiae

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Silver Gull (Red-billed) Chroicocephalus novaehollandiae scopulinus Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Chroicocephalus novaehollandiae scopulinus (Forster, 1844)

Definitions

- CHROICOCEPHALUS

- novaehollandae / novaehollandia / novaehollandiae

- scopulina / scopulinus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Distribution

Editor's Note: Additional distribution information for this taxon can be found in the 'Subspecies' article above. In the future we will develop a range-wide distribution article.

Habitat

Both coastal and inland locations , frequenting sandy and rocky shores, parks, beaches and rubbish dumps, as well as inland fields; some birds frequent slaughterhouses and livestock pens. Breeds on small islands and points, mainly with low vegetation, mainly offshore, but also on freshwater and brackish lakes; off South Australia mostly on marine islands, but also on islands in lakes, on breakwaters, and on causeways in salt-pans; in New Zealand, breeds on rocky beaches, islands, and stacks, rarely on inland lakes, but even here occasionally recorded at altitudes up to c. 900 m.

Movement

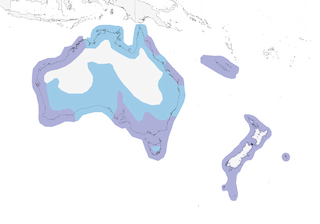

Nominate race may wander widely outside breeding season: some populations move short distances, mainly from colony to nearby coastlines, while S populations more likely to migrate N; general movement in E Australia is N, but in W Australia is S; some W movement also takes place along S coast. Sometimes make long return day trips from colonies, e.g. Sydney to Wollongong I. Race scopulinus leaves breeding areas in mid-January; most adults remain within 380 km of colony, while juveniles disperse further north, but adults ringed at Kaikoura have reached North I (Auckland). Species is an occasional visitor to Norfolk (both nominate scopulinus), Lord Howe and Kermadec Is, New Guinea (mainly S) and is a vagrant to Vanautu and Bali. Longest recorded movement of bird banded as chick 3256 km; longest recorded movement of bird banded as juvenile 2186 km; and longest recorded movement of bird banded as adult 2144 km.

Diet and Foraging

Very varied. The natural diet includes cnidarians, squid, annelids, insects, crustaceans, arachnids, small fish, frogs, birds and mammals, as well as some plant material, such as seed and berries (2). In race scopulinus, in breeding season, mainly euphausiid krill (Nyctiphanes australis) and other planktonic crustaceans, but also earthworms, insects and small fish; at other times diet more varied, including more fish and refuse. Mainly forages diurnally, but also at night. The nominate race has been observed on water’s surface 30 km offshore, eating pelagic amphipods (Hyperia gaudichaudi) and race scopulinus has been observed forming feeding frenzies with other seabirds and dolphins; inland flocks feed similarly on brine-shrimps. Patrols the edge of seabird colonies. In some disturbed colonies, opportunistically takes eggs of conspecifics. Occasionally steals food from terns and pelicans, but also a variety of other birds including cormorants, herons and shorebirds: including migrant Bar-tailed Godwits Limosa lapponica (3). Scavenges along shore. Often seen hawking flying ants (sometimes in large flocks of up to 3000 birds); kelp-fly larvae and locust swarms attract large flocks.

Food of anthropogenic origin, including refuse from rubbish dumps and garbage bins, and fish offal, is extremely important in urban areas, where the largest colonies in Australia now occur (4). In Sydney, refuse is an important constituent of the diet during the breeding season for 85% of adults, while 5–25% feed mainly on natural foods; the amount of natural food increases once chicks hatch. Feeding in ploughed fields is a relatively recent occurrence, but now common in both Australia and New Zealand. A frequent visitor at picnic sites.

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Noisy; commonest call, loud harsh grating squeal, “kwarr” or “kwe-aarrr”; also gives frantic-sounding, rapid yelping notes. Many calls associated with display or aggression, e.g. long, loud “haaaarrr-haaaarrrr-haaaarrrr-haaaarr” in challenge to a rival, and repeated clear “aou-aou-aou-aou” in alarm, which is frequently given when people in colony.

Breeding

Recorded in all months. Lays from March to November in W Australia, some pairs raising two broods per year; from July in S; ‘winter’ breeder in N; for race scopulinus, most data from 29-year study of Kaikoura colony (NE South I), where begins nesting July, prolonged egg-laying (late September to December), with peak in October (mid November on subantarctic islands); July–October in New Caledonia. Older birds nest earlier, and produce more young. Territory defended for long period in race scopulinus; nest building begins 2–3 weeks prior to laying; courtship feeding rare until c. 3 weeks before laying; mounting begins about same time, often following feeding. Often chooses same territory and mate in successive years. Colonial , occasionally solitary. May nest close to terneries, particularly of the Greater Crested Tern Thalasseus bergii, as does Hartlaub's Gull L. hartlaubii in Africa, but also with other seabirds occasionally. In tropical areas colonies tend to be small (3–25 pairs); up to 3000 pairs in South Australia; colony size limited by immediate food availability. In Capricorn Group in Great Barrier Reef, nests mostly on ground (on sand, low vegetation, rocks ), under trees and shrubs, sometimes in bushes up to 2·5 m up; closer than random to trees, with greater vegetation cover, but less grass around nest. Nests vulnerable to flooding. Nest a shallow cup of grass, samphire, rushes, thistle stems, old remiges, dry seaweed, or whatever material is available. Fidelity to natal colony varies dramatically, from 42% in New Zealand to 80% in South Australia.

Clutch is usually three eggs (1–6) in nominate, but more typically two in race scopulinus, generally between green and brown, occasionally blue-green, with variable darker markings, size 46·2–60 mm × 33·8–42 mm, mass 30–47 g; eggs and clutch sizes smaller in drought years or when food is otherwise scarce, and in scopulinus older females lay larger eggs; incubation 19–27 days (22–26 days in scopulinus) by both sexes; chick hatches in brown to greyish-brown down, remains in colony until c. 4 weeks, when led away by parents; parental care ceases at c. 6 weeks. Locally, Little Eagles (Hieraaetus morphnoides) may be important predators of chicks. Productivity low in scopulinus, with predation accounting for 25% mortality of eggs and 17% of chicks : c. 33% of adults never fledge young in their lifetime, and only 17% of males and 24% of females recruited young into population; breeding success and breeding effort in this race are strongly correlated with El Niño Southern Oscillation events and availability of prey species. First breeding usually at four years, sometimes three (even two in scopulinus, in which males breed at younger age than females); c. 24% of ringed chicks returned to colony at two years, but < 1% produced young. Reproductive life c. 11 seasons.

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). Abundant and increasing, especially in S of range. Over 500,000 pairs at c. 200 colony sites in Australia, some of which number 40,000–50,000 pairs, some of which were founded only very recently. Occasionally a pest at airports, and at colonies of other seabird species. Has declined locally with increases in other seabirds such as Kelp Gull (Larus dominicanus) and Australian Gannet (Morus serrator). Breeding in New Caledonia is confirmed (5). Population of race scopulinus probably also > 500,000 pairs. As with many gulls, its numbers increased dramatically through most of 20th century, benefiting from supplementary winter food at fish-processing plants and rubbish dumps. Legislation limiting discharge of offal was followed by a decline in numbers. Colonization of inland area of L Rotorua (North I) was facilitated by agricultural practices making food available.

Eggs are subject to predation by stoats Mustela erminea, and Little Eagles Hieraaetus morphnoides have been found to prey on gull chicks on Penguin Island, off W Australia (6). Both the Australian and New Zealand subspecies are identified as potentially subject to local declines from food shortage due to reductions in zooplankton availability that could result from projected climate change (7). Nevertheless, this species (L. n. scopulinus) is one in which there is evidence that a climate-associated phenotypic change, in this case a reduction in body mass during 1958–2004 as ambient temperatures increased, is due to phenotypic plasticity rather than to a genetic microevolutionary response (8).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding