White-chinned Woodcreeper Dendrocincla merula Scientific name definitions

Text last updated January 1, 2003

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Catalan | grimpa-soques de barbeta blanca |

| Dutch | Witkinmuisspecht |

| English | White-chinned Woodcreeper |

| English (United States) | White-chinned Woodcreeper |

| French | Grimpar à menton blanc |

| French (France) | Grimpar à menton blanc |

| German | Weißkinn-Baumsteiger |

| Japanese | シロアゴコオニキバシリ |

| Norwegian | hvithaketreløper |

| Polish | łaźczyk białogardły |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | arapaçu-da-taoca |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Arapaçu-da-taoca |

| Russian | Белобородый древолаз |

| Serbian | Belobrada puzavica |

| Slovak | kôrolezec bielobradý |

| Spanish | Trepatroncos Barbiblanco |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Trepatroncos Barbiblanco |

| Spanish (Peru) | Trepador de Barbilla Blanca |

| Spanish (Spain) | Trepatroncos barbiblanco |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Trepador Barbiblanco |

| Swedish | vithakad trädklättrare |

| Turkish | Ak Gıdılı Tırmaşık |

| Ukrainian | Грімпар білогорлий |

Dendrocincla merula (Lichtenstein, 1820)

Definitions

- DENDROCINCLA

- merula

- Merula

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

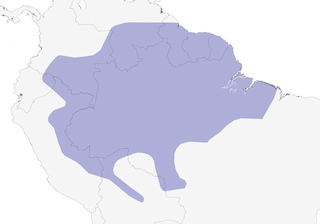

Seven subspecies of the exclusively Amazonian White-chinned Woodcreeper are generally recognized, but it seems plausible that the nominate subspecies and D. m. obidensis, which are both restricted to areas north of the Amazon and east of the Rio Negro, are better treated as a species apart, based on differences in their songs, size, and eye color. Over its wide range, from southern Venezuela south to northeastern Bolivia, this woodcreeper inhabits a variety of forest types, but it is principally found in terra firme and floodplain regions, and is only usually observed at the fringes of seasonally flooded forests. This obligate follower of army ant swarms, which takes most of its vertebrate and invertebrate prey on or close to the ground, appears to be uncommon over the vast majority of Amazonia, perhaps as a result of it being out-competed by many of the larger ‘professional’ antbirds at many localities over western and southern localities; where these species are absent, the White-chinned Woodcreeper seems more numerous.

Field Identification

Systematics History

Editor's Note: This article requires further editing work to merge existing content into the appropriate Subspecies sections. Please bear with us while this update takes place.

Formerly included the taxon meruloides, now considered to be closer to D. fuliginosa. Races W of R Negro together with those S of R Amazon may constitute a separate species, on basis of differences in vocalizations, size and iris colour; more work needed. Seven subspecies recognized.Subspecies

Dendrocincla merula bartletti Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Dendrocincla merula bartletti Chubb, 1919

Definitions

- DENDROCINCLA

- merula

- Merula

- bartletti / bartlettii

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Dendrocincla merula merula Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Dendrocincla merula merula (Lichtenstein, 1820)

Definitions

- DENDROCINCLA

- merula

- Merula

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Dendrocincla merula obidensis Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Dendrocincla merula obidensis Todd, 1948

Definitions

- DENDROCINCLA

- merula

- Merula

- obidensis

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Dendrocincla merula remota Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Dendrocincla merula remota Todd, 1925

Definitions

- DENDROCINCLA

- merula

- Merula

- remota / remotum / remotus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Dendrocincla merula olivascens Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Dendrocincla merula olivascens Zimmer, 1934

Definitions

- DENDROCINCLA

- merula

- Merula

- olivascens

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Dendrocincla merula castanoptera Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Dendrocincla merula castanoptera Ridgway, 1888

Definitions

- DENDROCINCLA

- merula

- Merula

- castanoptera / castanopterum / castanopterus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Dendrocincla merula badia Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Dendrocincla merula badia Zimmer, 1934

Definitions

- DENDROCINCLA

- merula

- Merula

- badia

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Distribution

Editor's Note: Additional distribution information for this taxon can be found in the 'Subspecies' article above. In the future we will develop a range-wide distribution article.

Habitat

Movement

Diet and Foraging

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

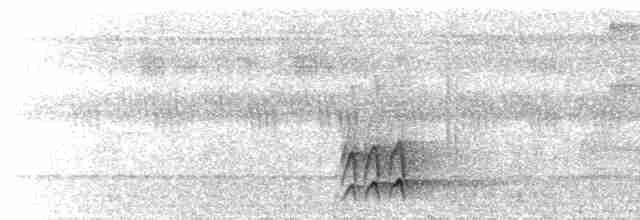

Calls often heard near ant swarms, but songs poorly known; both vary geographically. Most frequent vocalization a multi-note chatter call, often given at ant swarms, usually 2–4 notes, described as “dit-it-it-it” or “tat-at-at” over most of range, but piercing “deet-eet-ee” in N Amazonia E of R Negro. Song in Manaus area (Brazil) a series of 6–9 loud, whistled notes described as “kew, kew, kew, kew, kew, kewp”, but over most of range apparently lower in frequency and described as “we, wi, di, dit”, or “wi-wid-wid-di” in SE Colombia, and in some places an ascending whistle of 2–3 notes. Other calls include sharp “spee” notes in Manaus area, growling “chauhhh”, long rattle at 4–5 notes per second (i.e. slower than D. fuliginosa), quiet “wi-i-i-i-ih” rattle, also “tsiriRIT” possibly as warning call.

Breeding

Conservation Status

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding