Yellow-eyed Penguin Megadyptes antipodes Scientific name definitions

- EN Endangered

- Names (23)

- Monotypic

Text last updated May 22, 2013

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Bulgarian | Жълтоок пингвин |

| Catalan | pingüí ullgroc |

| Croatian | žutoglavi pingvin |

| Czech | tučňák žlutooký |

| Dutch | Geeloogpinguïn |

| English | Yellow-eyed Penguin |

| English (United States) | Yellow-eyed Penguin |

| Finnish | keltasilmäpingviini |

| French | Manchot antipode |

| French (France) | Manchot antipode |

| German | Gelbaugenpinguin |

| Icelandic | Tígulmörgæs |

| Japanese | キンメペンギン |

| Norwegian | guløyepingvin |

| Polish | pingwin żółtooki |

| Russian | Великолепный пингвин |

| Serbian | Žutooki pingvin |

| Slovak | tučniak žltooký |

| Spanish | Pingüino Ojigualdo |

| Spanish (Spain) | Pingüino ojigualdo |

| Swedish | gulögd pingvin |

| Turkish | Sarı Sürmeli Penguen |

| Ukrainian | Пінгвін жовтоокий |

Megadyptes antipodes (Hombron & Jacquinot, 1841)

Definitions

- MEGADYPTES

- antipoda / antipodes / antipodum / antipodus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

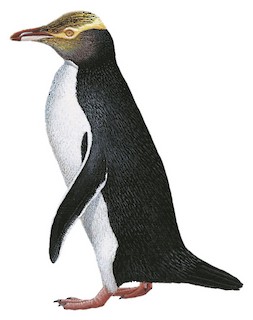

Field Identification

66–76 cm; 3·6–8·9 kg. The only penguin with pale yellow band through eye . Adult has light straw-yellow feathers with black shaft streaks on cap and anterior face down to chin and throat, becoming plainer and more brownish on lower throat and on rear face and side of neck, the nape crossed by obvious pale yellowish band that extends through side of head to eye, where it creates a spectacle-like appearance; lower nape and upperparts blackish with paler slaty-blue feather tips, this dark area reaching to around axillary region (but not in front of it); upperside of flipper blue-black with very thin (marginal) white leading edge (meeting white of side of breast) and an obvious, complete white trailing edge (broader than on most other penguin species), underside of flipper whitish or pinkish with a dark patch at rear base; tail blue-black; foreneck to undertail-coverts white; iris light yellowish, bare pink or greyish-pink orbital ring; upper mandible reddish, often duskier on basal culmen, with whitish-pink area between nostril and broad tip, lower mandible whitish-pink to pale greyish except for reddish tip; legs pink, soles and rear tarsus dusky grey. Leucistic adult with "normal" ones Another leucistic adult have been reported. Sexes alike, male having on average slightly longer head and foot than female (1). Juvenile is similar to adult, but light yellow replaced by pale brownish or greyish, so that head looks much drabber, the pale band on nape to eye obscure or lacking because of narrow blackish shaft streaks, and chin and throat mostly white.

Systematics History

Subspecies

Distribution

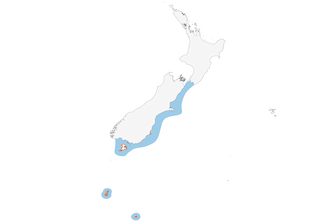

New Zealand: E & SE South I, Stewart I, Codfish I, Auckland I and Campbell I.

Habitat

Marine. Breeds in areas with dense vegetation near coast , mainly on slopes, in gulleys or on cliff tops. Occupies shallow coastal waters; forages mostly inshore.

Movement

Adults mainly sedentary, occurring along coast near breeding grounds throughout the year. A radiotracking study on the Otago peninsula found that the foraging range of breeding birds is relatively short: a median distance of 13 km and a maximum of 57 km (3). However, some adults migrate N, as much as 500 km. Pre-moult period at sea c. 23 days. Juveniles disperse to N, often reaching Cook Strait, up to 600 km from nesting grounds.

Diet and Foraging

Mostly fish, especially red cod (Pseudophycis bachus), opalfish (Hemerocoetes monopterygius), New Zealand blueback sprat (Sprattus antipodum) and argentines (Argentina), also some cephalopods, e.g. New Zealand arrow squid (Nototodarus sloanii), and a few crustaceans; diet varies with season and locality. In study on SE coast of South I during four breeding seasons from Feb 1991 to Dec 1993, 198 stomach samples from 86 individuals examined contained 43 identified prey types, including 37 species of fish, four of cephalopod and several crustacean species, most items less than 25 cm in length: seven of these (six fish, one squid) accounted for 90% of biomass and 60% of total prey number, and all fish combined comprised 90% of biomass and 80% of prey number; opalfish (a bottom-dwelling species) was main component of diet in terms of total biomass, number and frequency, other important components including species found on or near the bottom, e.g. blue cod (Parapercis colias), arrow squid, silverside (Argentina elongata) and red cod, with pelagic prey such as sprat and the krill Nyctiphanes australis present in smaller numbers; percentages of several prey species varied significantly over study period, e.g. increased proportions of red cod and opalfish and fewer blue cod and arrow squid in 1992–1993 (a season with improved breeding success). (4) Captures prey by means of pursuit-diving , diving down to at least c. 100 m, but usually only to c. 34 m.

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Not so noisy as most other penguins. In display gives musical trilled notes , high-pitched pulsating yells and grunts. Contact call a pair of disyllabic high notes.

Breeding

Nests occupied in Aug–Sept, egg-laying in Sept–Oct. Solitary or in small, loose aggregations. Nest placed between roots in coastal forest or scrub or in middle of tussac-grass thicket. Clutch 2 eggs ; incubation by both sexes, period 39–51 days, with stints of 1–7 days; first down cocoa-brown, second down slightly paler brown ; young do not form crèche; fledging at 97–119 days, in Feb–Mar. Breeding success 0·9–1·4 chicks per nest. Monitoring for six seasons in 1991–1996 at two breeding sites on Otago Peninsula (E coast of South I) revealed inverse relationship between breeding success and total number of nests, suggesting that influx of inexperienced breeders reduces average success: proportion of adults not breeding in any one season at either site ranged from zero to 13% for males and zero to 23% for females; between 75% and 92% of breeders nested in two consecutive seasons, while 0–6% of breeders missed one season and 9% of females (no males) skipped two consecutive seasons. (5) Sexual maturity at 2–3 years of age for females, 4–5 years for males. Average annual survival over four seasons at two sites on Otago Peninsula 93% for males and 90% for females (5).

Conservation Status

ENDANGERED. This species has a very small breeding range, within which it is thought to be declining. According to recent information summarized by BirdLife, estimated global population c. 1626–1676 pairs, of which 523 on South I coast, 178 on Stewart I and adjacent Codfish I, 520–570 in Auckland Is and 405 on Campbell I. South I population formerly much larger, but numbers on SE coast (Catlins) fell by at least 75% between late 1940s and 1990, habitat loss apparently a major cause; on Otago Peninsula, severe mortality event in 1986 and another in 1990 each reduced number of pairs by 50%. Ground searches on Stewart I and Codfish I in 1984–1994 produced surprisingly low total of 220–400 breeding pairs, of which c. 170–320 on former and its outliers and 50–80 on Codfish (6); comprehensive survey in 1999, 2000 and 2001 revealed reduction to 79 pairs in 19 discrete groups on Stewart I (where cats present) and 99 pairs in ten discrete sites on all cat-free islands, majority (61 pairs) on predator-free Codfish I (25 km coastline) (7); small numbers and small groupings found on Stewart I (coastline 673 km) compared with Codfish I (coastline 25 km) suggest that predation may be a factor in suppressing population on former. Numbers on Campbell I declined between 1987 and 1998 (8). Main threats include destruction of suitable nesting habitat (nesting birds require sufficient shade and tranquility), especially forested areas along coasts with shallow water; habitat often removed to make way for farmland, leading to additional disturbance. Introduced mammalian predators, including ferrets (Mustela furo), stoats (Mustela erminea) and domestic/feral cats, are a major problem on South I, causing significant losses of both chicks and eggs; degree of threat posed by cats on Stewart I unclear, as high rate of chick mortality caused by starvation and disease. Cats present also on main Auckland I, but absent from Enderby I (off NE coast), and absent also from Campbell I and Codfish I. Predation by pigs occurs on main Auckland I, but impact of this not known and could be significant; livestock can also have serious effects through trampling and general habitat destruction, as well as disturbance. Hooker's sea-lions (Phocarctos hookeri) kill and eat 20–30 of these penguins annually on Otago Peninsula (9); this behaviour by the sea-lions, first reported in this area in 1996 and 1997 (10), was observed a decade earlier on Campbell I (11). Population crashes may sometimes be due to avian malaria or biotoxins, and food shortages caused by sea-temperature changes can be a problem at times. Disease appears to be a major problem in some years within some populations, with diphtheritic stomatitis (caused by the bacterium Corynebacterium amycolatum) (12) and a Leucocytozoon blood parasite (13) major causes of chick mortality; 50% of chicks on South I were killed by diphtheritic stomatitis in 2004. Human disturbance, including visits by tourists to colonies, can have adverse effects, and other known dangers include fishing nets, in which penguins can be caught and eventually drown.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding