Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens Scientific name definitions

Text last updated January 1, 2002

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Asturian | Fregata magnñfica |

| Bulgarian | Великолепна фрегата |

| Catalan | fregata magnífica |

| Croatian | veliki brzan |

| Czech | fregatka vznešená |

| Danish | Pragtfregatfugl |

| Dutch | Amerikaanse Fregatvogel |

| English | Magnificent Frigatebird |

| English (United States) | Magnificent Frigatebird |

| Finnish | keisarifregattilintu |

| French | Frégate superbe |

| French (France) | Frégate superbe |

| Galician | Rabiforcado magnífico |

| German | Prachtfregattvogel |

| Greek | Μεγάλη Φρεγάτα |

| Haitian Creole (Haiti) | Sizo |

| Hebrew | פריגט הדור |

| Hungarian | Pompás fregattmadár |

| Icelandic | Freigátufugl |

| Japanese | アメリカグンカンドリ |

| Lithuanian | Puošnioji fregata |

| Norwegian | praktfregattfugl |

| Polish | fregata wielka |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | fragata |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Rabiforcado-magnífico |

| Romanian | Fregată mare |

| Russian | Великолепный фрегат |

| Serbian | Velika fregata |

| Slovak | fregata vznešená |

| Slovenian | Lepa burnica |

| Spanish | Rabihorcado Magnífico |

| Spanish (Argentina) | Ave Fragata |

| Spanish (Chile) | Ave fragata magnífica |

| Spanish (Costa Rica) | Rabihorcado Magno |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Rabihorcado |

| Spanish (Dominican Republic) | Tijereta |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Fragata Magnífica |

| Spanish (Honduras) | Fragata Tijereta |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Fragata Tijereta |

| Spanish (Panama) | Fragata Magnífica |

| Spanish (Peru) | Avefragata Magnífica |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Tijereta |

| Spanish (Spain) | Rabihorcado magnífico |

| Spanish (Uruguay) | Fragata |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Tijereta de Mar |

| Swedish | praktfregattfågel |

| Turkish | Muhteşem Fregatkuşu |

| Ukrainian | Фрегат карибський |

Fregata magnificens Mathews, 1914

Definitions

- FREGATA

- fregata

- magnificens

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

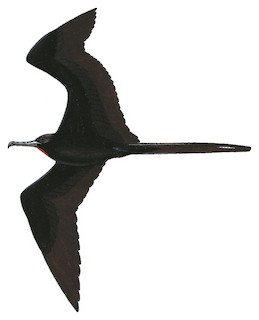

With their long, pointed wings and deeply forked tail, frigatebirds present a distinctive flight silhouette. They seem to soar effortlessly throughout the day and are rarely seen to flap their wings; yet their great aerial agility enables them to chase and harass other birds until the chased bird regurgitates a recently caught meal, whereupon the frigatebird darts down, catching the food before it hits the ocean. While frigatebirds have a reputation of being pirates-reflected in their colloquial name 'Man-o'-War Bird'-they catch most of their food on their own, by snatching fish or squid from near the ocean surface, never wetting a feather. This species lacks waterproof plumage and is rarely, if ever, seen to sit on the water. While adept in the air, frigatebirds have short legs and small feet, and never walk or swim.

The frigatebird family is perhaps the most distinctive among the order Pelecaniformes. Anatomically, they are the only bird family with a fused pectoral girdle, and the vestigially-webbed feet set on very short legs attracted Darwin's (Darwin 1859) attention as an example of a phyletic vestige with no current adaptive value. This is the only seabird family with obvious sexual dimorphism in plumage; sexes also differ in size, females being larger and 11-23% heavier than males (Osorno 1996). Males are known for their bright red inflatable gular sac, which they use to attract females during courtship. In a spectacular courtship display, males sit in varying size groups, sacs all inflated, clattering their bills, waving their heads back and forth, quivering their wings, and calling to females flying overhead. Frigatebirds often nest in large, dense colonies where individuals on adjoining nests can reach out and touch their neighbor. The breeding period is exceptionally long and young fledglings are often still being fed by the female at one year of age. In the Magnificent Frigatebird, sexual dimorphism also extends to the breeding cycle; males abandon their mate and half-grown chick and leave the colony, presumably to molt and return for another breeding attempt, with a different mate, while the female provides protracted postfledging care to the young of the previous season. This allows males to breed annually while females breed only in alternate years; in no other seabird of any species are the sexes thought to breed on cycles of different lengths.

The Magnificent Frigatebird nests on islands throughout the Caribbean, and in tropical areas of both coasts of Middle and South America. Its range overlaps that of the Great Frigatebird (Fregata minor) in the Galápagos Is. and Central America. Pairs build twig nests in trees or bushes, with males providing the material while females do the actual building. Human disturbance and introduced predators have extirpated many historic colonies and this will probably continue as more and more coastal areas in the species' range are developed.

There have been few studies of the Magnificent Frigatebird, but it is probably now the best-known of the 5 species in the family. The colony on Barbuda, eastern West Indies, was studied by Diamond (Diamond 1972a, Diamond 1973b), who first described the desertion of the young by males and suggested that this might enable males to breed annually while females were still feeding the young from the previous season. Subsequent studies in Belize (Parker et al. 1987, Trivelpiece and Ferraris 1987) and Mexico (Osorno et al. 1992; Carmona et al. 1995; Osorno Osorno 1996, Osorno 1999; Calixto-Albarran and Osorno 2000) have added greatly to our knowledge of the Magnificent Frigatebird's breeding biology and behavior but have neither confirmed nor refuted Diamond's hypothesis. The unique features of the breeding cycle of this species, and its implications for life-history theory (Osorno 1999), require multiyear studies of marked individuals to establish the breeding periodicity of the two sexes.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding