Song Thrush Turdus philomelos Scientific name definitions

Text last updated January 13, 2013

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Albanian | Tusha këngëtare |

| Arabic | سمنة مغردة |

| Armenian | Երգող կեռնեխ |

| Asturian | Malvñs comñn |

| Azerbaijani | Oxuyan qaratoyuq |

| Basque | Birigarro arrunta |

| Bulgarian | Поен дрозд |

| Catalan | tord comú |

| Chinese (SIM) | 欧歌鸫 |

| Croatian | drozd cikelj |

| Czech | drozd zpěvný |

| Danish | Sangdrossel |

| Dutch | Zanglijster |

| English | Song Thrush |

| English (United States) | Song Thrush |

| Faroese | Ljómtrøstur |

| Finnish | laulurastas |

| French | Grive musicienne |

| French (France) | Grive musicienne |

| Galician | Tordo común |

| German | Singdrossel |

| Greek | (Κοινή) Τσίχλα |

| Hebrew | קיכלי רונן |

| Hungarian | Énekes rigó |

| Icelandic | Söngþröstur |

| Italian | Tordo bottaccio |

| Japanese | ウタツグミ |

| Latvian | Dziedātājstrazds |

| Lithuanian | Strazdas giesmininkas |

| Mongolian | Дууч хөөндэй |

| Norwegian | måltrost |

| Persian | توکای باغی |

| Polish | śpiewak |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Tordo-pinto |

| Romanian | Sturz cântător |

| Russian | Певчий дрозд |

| Serbian | Drozd pevač |

| Slovak | drozd plavý |

| Slovenian | Cikovt |

| Spanish | Zorzal Común |

| Spanish (Spain) | Zorzal común |

| Swedish | taltrast |

| Turkish | Öter Ardıç |

| Ukrainian | Дрізд співочий |

Turdus philomelos Brehm, 1831

Definitions

- TURDUS

- turdus

- philomelos

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

20–23 cm; 50–107 g. Nominate race is plain brown above, slightly more olive-tinged on rump, weak buff spotting on wing-coverts, vague dark auricular bar and buff-streaked cheeks; plain buffy-white submoustachial streak and chin divided by dark malar; whitish below with buff tinges, especially across breast and on flanks, with rather regular dark spotting from breast to belly and flanks; yellowish-buff underwing-coverts; bill dark, paler base; legs pinkish. Differs from similar Chinese Thrush (Turdus mupinensis) mainly in plainer face, smaller spots below. Sexes similar. Juvenile is like adult, but buffier on head, buff-streaked on mantle and scapulars. Race hebridensis is darker brown above than nominate, with rump greyish-tinged, less extensive buff and larger spots below, underwing-coverts more orangey; <em>clarkei</em> is intermediate between previous and nominate; nataliae is very slightly larger and paler, rump more uniform with upperparts.

Systematics History

Editor's Note: This article requires further editing work to merge existing content into the appropriate Subspecies sections. Please bear with us while this update takes place.

Earlier name T. ericetorum invalid. Races intergrade. Race nataliae very similar to nominate. Four subspecies recognized.Subspecies

Nominate race introduced to SE Australia, Norfolk I, Lord Howe I and New Zealand (including surrounding islands from Kermadec S to Campbell and Macquarie) (1).

Turdus philomelos hebridensis Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Turdus philomelos hebridensis Clarke, 1913

Definitions

- TURDUS

- turdus

- philomelos

- hebridalis / hebridensis / hebridicus / hebridium

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Turdus philomelos clarkei Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Turdus philomelos clarkei Hartert, 1909

Definitions

- TURDUS

- turdus

- philomelos

- clarkei

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Turdus philomelos philomelos Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Turdus philomelos philomelos Brehm, 1831

Definitions

- TURDUS

- turdus

- philomelos

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Turdus philomelos nataliae Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Turdus philomelos nataliae Buturlin, 1929

Definitions

- TURDUS

- turdus

- philomelos

- nataliae

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

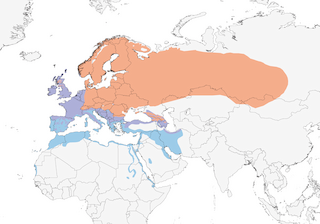

Distribution

Editor's Note: Additional distribution information for this taxon can be found in the 'Subspecies' article above. In the future we will develop a range-wide distribution article.

Habitat

Breeds in almost all types of temperate forest and woodland, generally in lowlands and valleys but reaching tree-line in Switzerland (1600–2200 m) and Russia (1200 m), and found mainly at 500–1900 m in Turkey; key features of habitat are patches of trees and bushes with small areas of open moist ground (grassland or litter-rich soil) supporting abundant invertebrate fauna. Nominate race favours spruce (Picea) forest, while clarkei and hebridensis occupy deciduous forests and even fairly open, seemingly marginal habitats such as heath-covered inshore islands and sparse hillside birch (Betula) woods (Scotland) and scrubby steppe (Armenia). In natural beech (Fagus sylvatica) area of 213 ha in Switzerland, 79 (81%) of 98 territories were in spruce patches although spruce covered only 16% of area. Original occupation of old forests, both deciduous and coniferous, perhaps borne out by findings of studies in farmed landscape in E Britain, where race clarkei uses gardens (71·5% of territories in 2% of total area) and woodland (22·7% in 1% of total area) but has poor breeding success in farmland itself; declines and losses far greater in gardens and small woods (20–30% extinction rates) than in large woods, implying that latter, despite holding lower densities than gardens, may be optimal. Has nonetheless adapted well to modern lowland agricultural and urban landscapes, breeding in small woodlots, parkland, orchards, mature hedgerows, overgrown railway embankments, roadsides, cemeteries, and suburban gardens with some tall trees. Non-breeding areas somewhat drier in S of range, and in Morocco winters mainly in low and tall scrub and trees, also orchards and vineyards, euphorbia, Argon bush, Salicornia, Ilex woods, and forests at up to 2700 m, in Tunisia in deciduous forest and olive groves, in Israel mainly in areas with mixed trees and thickets in natural and agricultural land, gardens, orchards and woodland, in Sudan in arid open bush to 1050 m, in Eritrea in acacia (Acacia) bush along coast, sometimes in high moorland, in Saudi Arabia in palm groves and on waste land, and in United Arab Emirates in large gardens, fields, palm groves, irrigated light woodland and parks.

Movement

Mainly migratory ; populations in W & S of breeding range sedentary, partial migrants or short-distance movers over winter period (in Britain, 50% of adults and 67% of first-years move). Breeders in Scandinavia, Germany and Switzerland migrate generally SW into Iberia and W Mediterranean; those at highest latitudes (and especially first-years) move farthest, to winter in broad band across N Africa (similarly, migrants from N Britain found farther S in Iberia than are those from S Britain); passage from late Aug and continuing Sept–Nov; present in Morocco Sept–May, with most passage mid-Oct to late Nov and Feb to end Mar. Populations from EC Europe take more SE direction, wintering from Italy E to Cyprus, and those in European Russia and Siberia winter in NE Africa, Middle East and Iran. Siberian birds migrate from mid-Sept, more S populations (in C Asia) remaining into Nov. Very common passage migrant and winter visitor in Israel, autumn peak Nov and spring peak first half Mar; passage and wintering in Jordan early Nov to early Apr. Commonest migrant thrush in Bahrain and United Arab Emirates Nov–Mar, with similar dates in coastal zone of E Saudi Arabia. Winter visitors occupy Red Sea coast of Sudan Oct–Mar, Eritrea late Nov to late Mar and Djibouti Dec–Mar; scattered records in Sahelian countries, and one from as far S as N Central African Republic. Leaves N Africa late Mar to early Apr, but individuals appear relatively site-faithful and route-faithful, so schedules probably different for different breeding populations (and/or for different cohorts and sexes within them); certainly, spring migration in France exhibits two peaks, in early and late Mar. Movement through NW Europe Mar to mid-May, arrivals in N of range from Scandinavia to Siberia from mid-Apr into May. No information on schedule of movements in SW Asia; winter vagrant in Pakistan and India.

Diet and Foraging

Invertebrates and berries. Animal food in W Palearctic includes adult and larval beetles (Coleoptera) of at least 15 families, adult and larval flies (Diptera) of at least six families, adult and larval lepidopterans of at least six families, adult and larval neuropterans of at least three families, bugs (Hemiptera) of at least six families, orthopterans (crickets, bush-crickets, grasshoppers), hymenopterans (ants, sawflies and ichneumons), scorpion flies (Mecoptera), earwigs (Dermaptera), spiders, harvestmen (Opiliones), mites (Acarina), woodlice (Isopoda), sandhoppers (Amphipoda), millipedes (Diplopoda), centipedes (Chilopoda), snails , slugs and earthworms ; very rare reports of vertebrates, i.e. small frog (Rana temporaria) (2), lizard, slow-worm (Anguis) and shrew (Soricidae), taken or attacked. Plant food mainly fruits and seeds of barberry (Berberis), dogwood (Cornus), cotoneaster (Cotoneaster), crowberry (Empetrum), spindle (Euonymus), strawberry (Fragaria), ivy (Hedera), sea buckthorn (Hippophae), juniper (Juniper), honeysuckle (Lonicera), olive (Olea), cherries (Prunus), currant (Ribes), bramble (Rubus), elder (Sambucus), rowan (Sorbus), yew (Taxus), bilberry (Vaccinium), viburnum (Viburnum), mistletoe (Viscum), vine (Vitis), also spruce needles, clover (Trifolium) and turnip. Stomachs of 84 birds from throughout year, Britain, held 35·5% insects (largely adult and larval beetles), 15% earthworms, 5% slugs and snails, 1·5% other invertebrates, 41·5% fruits and seeds, and 1·5% grass, bread and other items. In suburban S Britain, Dec–Mar, earthworms constitute up to 94% of feeding records. Stomachs of 244 spring migrants from Heligoland (Germany) held 890 invertebrates, of which 35% by number snails, 28% adult insects (mostly beetles), 16% larval insects (mostly beetles and flies), 10% slugs, 9% earthworms and 2% others, 13% of stomachs also containing plant matter. Summer diet in Britain dominated by earthworms, snails, beetles and insect larvae (mainly Coleoptera and Lepidoptera), earthworms predominating Mar–Apr and snails Jun–Jul, and spiders becoming important in late summer; snails can also predominate in Jul–Sept, fruit becoming important Sept–Nov. In autumn and winter, SW France, 64% of stomachs held fruit, with juniper berries in 45%. In winter in Córdoba (Spain), stomachs of 130 birds held 69–82% (monthy averages by volume) fruit and seeds, notably (41–60%) olives, but snails important in some areas; in 155 stomachs from NE Spain and Mallorca 15 species of shelled snail identified (no slugs recorded), in Israel (Negev) large numbers of snails taken, and in Egypt desert snails (Eremina desertorum) recorded. Food brought to nestlings generally softer-bodied than summer adult diet; stomachs of 38 nestlings in Britain held 42 caterpillars, 9 maggots, 5 elaterid beetle larvae, 4 spiders, and remains of earthworms and slugs. Tends to forage more under bushes and trees, less in open, than do many congeners. Feeds close to cover on ground. Uses stones and other hard surfaces to smash snail shells ; shelled snails smaller than 1 cm swallowed whole.

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Song , by male, commonly (but not only) in relatively deep twilight, a very loud, vigorous, long-sustained series of short, fairly rapidly delivered phrases , each generally repeated 2–3 times, and each consisting of several strong, well-enunciated, richly whistled notes , varying in pitch (but higher and shriller than T. merula), emphasis and length (mostly all very short), e.g. “quitquitquitquit… quitquitquitquit… dudulidlít dudulidlít… codídio… codídido… filip filip filip filip… terrrrt terrrrt terrrrt… pichipíchi pichipíchi…”; song louder and more intense during counter-singing with rival male; song output over year has distinct phases, including extended one at end of breeding, possibly for repertoire-learning by offspring or territorial marking for subsequent season. Subsong, commonly by interacting males, a low twittering warble, and similar type of song given in courtship of female. Calls include anxious “tsipp” in short flight (often when flushed), high thin “siih” as warning of aerial predator, dry staccato “stuk-stuk-stuk” in mild excitement, and excited explosive chattering “tikikikikikik” in high alarm or anger (in breeding season); metallic “zilip” heard from spring migrants in S Caspian region.

Breeding

Mainly mid-Mar to mid-Aug in W Europe, starting a month later in C & N Europe; 2–3 broods in C & S of range; introduced population in New Zealand breeds end Jun to Dec. Territory size variable with habitat, as little as 0·2 ha but generally 0·4–0·6 ha in suburban mature gardens but 1·5–6 ha in woodland in Finland and France. Nest a neat cup of grass, twigs and moss , thick hard lining of clay, mud, dung or rotten wood, often mixed with leaves, placed in bush, shrub or tree, often against trunk, also in creeper on wall, in bank or on ledge; more often on ground in summer than in spring; typical nest in Switzerland placed in Norway spruce (Picea abies), on average 2·9 m up in tree 7·4 m high; in Poland, mean height of 196 nests 2·5 m, range 0–8 m. Eggs 3–5, greenish-blue with blackish-brown spots; incubation period 10–17 days, mean 13·5 days; nestling period 11–17 days, mean 13 days; post-fledging dependence variable but generally short, 1–3 weeks, partly dependent on whether further nesting attempt made. Average clutch size 3∙6 eggs (n = 367) in the population introduced in New Zealand, compared with 4∙1 eggs (n = 1155) in the source population in Britain; also smaller egg size and nestling period, but longer incubation period (3). In Swiss study, clutch loss 37% and nestling loss 33%; in Britain, hatching rate in one study 71% (739 eggs), fledging rate 78% (1034 nestlings) and overall success 55%, in another (involving 816 nests) 50% hatched and 36% fledged at least some young; failure rate during incubation generally increases significantly where corvids more abundant. Mortality in first year of life 53%, in second year 40%; annual overall mortality in Finland 54%; survival of first-years negatively correlated with duration of frost, adult survival negatively correlated with duration of summer drought; causes of mortality of ringed individuals in NW Europe are domestic predator 26%, human-related (accidental) 45%, human-related (deliberate) 12%, other 17%. Oldest recorded individual 13 years 9 months.

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). Generally common to fairly common; uncommon in Armenia. Total population in Europe in mid-1990s estimated at 14,127,336–18,470,086 pairs, with additional 100,000–1,000,000 pairs in Russia and 10,000–100,000 pairs in Turkey; Spain estimated then to hold 200,000–400,000 pairs, but more recently minimum population there calculated as 101,134 pairs (only possible problem judged to be hunting). By 2000, total European population (including European Russia and Turkey) revised to 20,000,000–36,000,000 pairs and considered generally stable. In 20th century range expanded N in Scandinavia, and species colonized many urban parks and suburban gardens, but population in Britain declined by 7% per year in 1975–1986, and concomitant declines in Ireland and parts of C Europe. Decline in Britain now of serious conservation concern; causes not understood, but populations in garden habitats may have been underestimated in recent censuses. Changes in agricultural practices have probably caused major reduction in availability of key summer food resources on lowland farmland: loss of hedgerows, scrub and permanent grassland with livestock, and wide-scale installation of under-field drainage systems (resulting in early soil drying and hence loss of topsoil earthworms), have probably all contributed to decline in UK arable farmland, while pesticides and predators are further suspects. Role of disturbance unclear; appears to inhibit colonization of parks, and may therefore have negative influence on breeding success. Hunting pressure considerable for many decades in Mediterranean, but no clear evidence for decline. Densities reach exceptional 1·5–3·4 pairs/ha (150–340 pairs/km²) in some anthropogenic habitats in W Europe, but normally 0·1–0·5 pairs/ha (10–50 pairs/km²), with e.g. 27 and 43 pairs/km² in two oak woodlands in S England, 40 pairs/km² in spruce forest but only 10 and 5 pairs/km² in broadleaf woodland and pine (Pinus) forest, respectively, in Finland. In winter, common to abundant in N Africa; in Morocco the most regular and abundant winter thrush and one of commonest migrants in N woodlands. Uncommon in C Saudi Arabia. Introduced populations in Australia and New Zealand stem from late 19th century, but little outward spread from Melbourne (Australia); populations on Lord Howe I and Norfolk Is appear to be self-introduced from New Zealand, as are those on Macquarie I; also well established on some of Kermadec Is.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding